Magic, Myth and Indian Kitsch: The Spectacular Aesthetic of EXCISE DEPT

EXCISE DEPT.

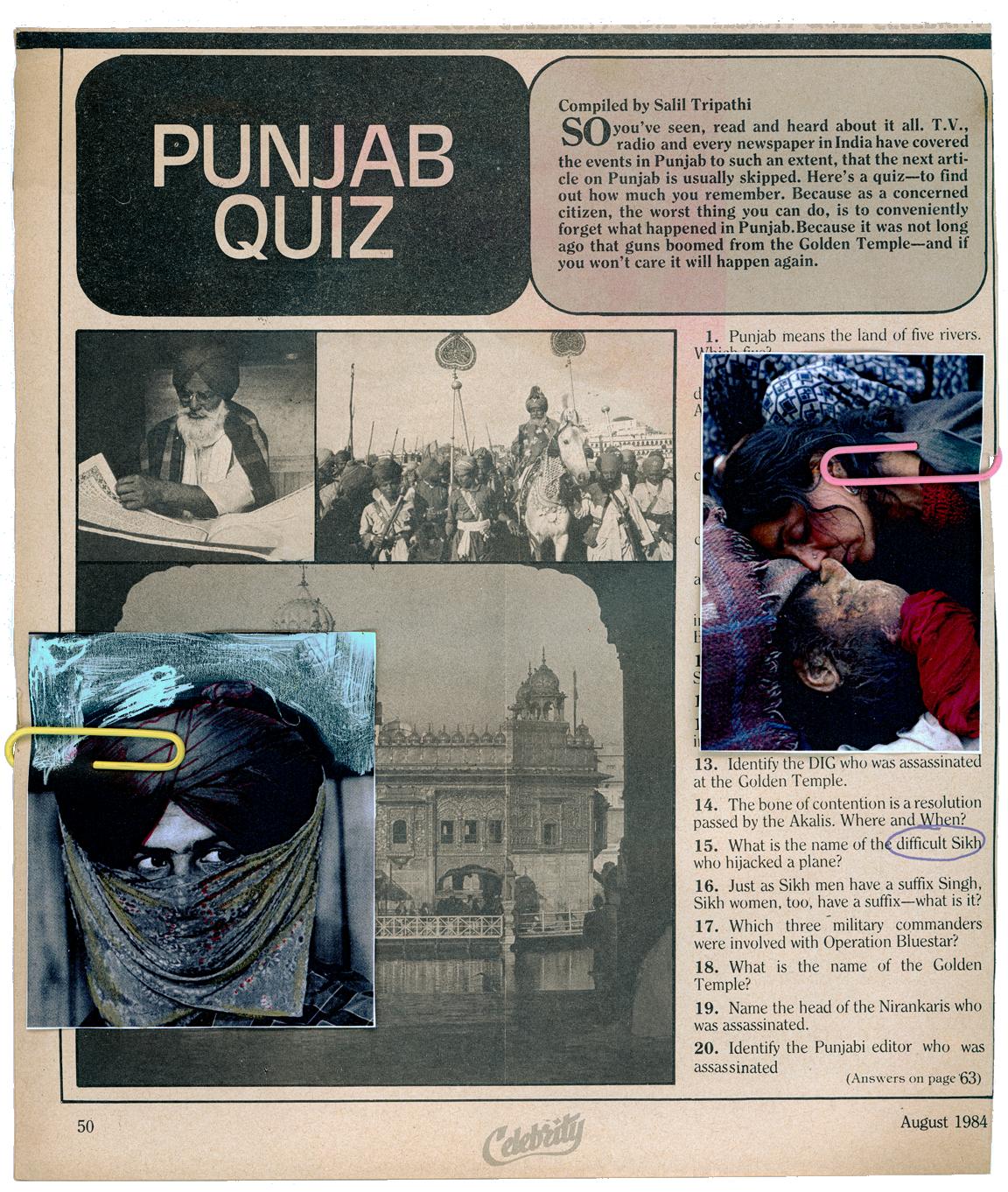

Navigating EXCISE DEPT’s psychedelic website is like a treasure hunt. As one sorts through digital sachets of tomato sauce, lottery tickets, dried leaves, dollar notes, letters, old photographs and newsprint, there are clues underneath that lead to inroads into their world. Clicking on a knife hidden underneath such paraphernalia leads to a documentary by Anand Patwardhan called In Memory of Friends (1990) on the Khalistan movement in Punjab. Towards the end is a calculator where various buttons lead to different hyperlinks of idiosyncratic things they have been consuming digitally until brain rot—an insight into the sharp political humour that constitutes their music. Their digitality hinges on the serendipity of user discovery.

In the third installment of this interview series, EXCISE DEPT delves into their creation of a digital universe from their personal lives and performing before the very powers they critique.

Still from EXCISE DEPT's interactive website.

Upasana Das (UD): You treat your website and social media as places for references—mostly visual. A couple of Anand Patwardhan films are linked in “ANGULIMAAL’s” clickable fingers on the website, and you had this fascinating film sequence on Gandhi as a ’90s B-movie villain, just beating everyone up and being everything he did not propagate! Or of a BJP MLA exercising.

Karanjit Singh (KS): That is Pranav Singh Champion; he was a BJP MLA in 2020. There were videos that were taken in his home when he was drinking whiskey with his boys and he was dancing with some woman and brandishing his revolver. So then he had to resign but the fellow is still going full power. Recently, he got into a big public fight with another MLA and showed up at this man's house with his goons with giant rifles, shooting in the air. If you see the arc of Pranav Singh Champion, he is a baller.

Rounak Maiti (RM): That video on our feed is from shitposting during the lockdown—a lot of random rips from YouTube and images—we were not doing it with much intention but creating some sense of a universe that we are all in. This was just one of the many hilarious reels that we saw of him doing some weird push-ups. How are you going to run a country if not for your core strength, bro? It is one of those absurd visuals, like discovering an alien totem or something. If you saw it with absolutely zero context, you would just be scratching your head. Last year, Nishant Mittal and I did this duo improvisation set in Delhi where I was playing ambient music on a synth and samples, and he was playing these weird old tape recordings he has in his collection—sound effects, meditation tapes, bird calls, etc. He is a close friend of ours. We did the cassette release with him; it was his first—and he is in the album art as well. He is the mantriji (minister). He is someone who is very much on the same kind of trip as us.

Still from 'LIFE'S A GAME'.

UD: “LIFE’S A GAME” was pretty surreal with the eggs and chicken in the microwave, or the never-ending sari, which is also magical and mythological.

KS: What came before—the chicken or the egg? It was Jatinder Singh—he came before everyone! (laughs)

UD: He even has a LinkedIn page, where he said he had fifty-seven years of experience doing magic.

KS: Wait, hold on—he has a LinkedIn page?! Wow, love it. When we were running pre-production on this, Rounak and I visited Mr Babbar. I said we have to figure out dates to shoot with him, but he said, “I am going to Ayodhya.” He came back from Ayodhya and said, “Everything is magic. Mandir tora nehi, sabh ko bata diya mandir ban gaya” (No temple was broken, and yet they have told everyone that the [new] temple has been made). He told us this story from the early 2000s or late 1990s, when he was performing a lot, I might have seen him live as a kid too. He was performing in a village in Punjab, and the Congress party had invited him to do a magic show for their campaign. At the end, the grand magic reveal would say, “Vote Congress.” Somebody in that audience was a BJP fellow who approached Mr Babbar at the end. He said, “Tomorrow, we have our campaign event. It is on the same ground. Can you come and do magic for us as well?” Babbar said, “Of course.” So, the next day he was there in saffron clothing, with a saffron turban, and did the same magic show for the same people, but now it was “Vote BJP.” He was a very politically neutral fellow; he was concerned only with magic.

Siddharth Vetekar (SV): We did not do that much to his house. That is actually how this man lives.

Still from 'LIFE'S A GAME'.

KS: So in many ways it is more documentary—the man just lives a very surreal life. There is one entire section of his godown under his flat where there is a giant tent in which he used to make an elephant disappear. Babbar sahab also has an insane collection of magic memorabilia. He used to do big stage shows, and all these older magicians were using wooden handcrafted props. So, he would oversee their painting and their aesthetic. All of that was in his storage room which he has not opened up since he stopped doing big shows in the mid-2000s. Sid and I went one day and asked him if we could raid his archive. He has insane photo archives. So, we scanned a bunch of images, and they looked so surreal and weird—levitating people, dislocating body parts and so on. I love that, at the end of the day, it is a sardarji doing these magic tricks that are borderline violent.

UD: Indian street and kitsch elements are very important to your visual language—bus tickets, carom, flower motifs painted on enamel and vintage calculators. Did that become important to you as you were delving into the ’80s and ’90s?

RM: It is all part of the tendency towards archiving and documentation. We have built a world—in our music, we are pulling from so many different sources, regions and styles, and visually from archival stuff, VHS rips and the internet. At the time, KJ and I were living together in Delhi, so a lot of it was a mix of these magazines that he picked up in the Daryaganj book market, along with printed ephemera, and then it extended into objects. Both of us have kept a lot of our family heirlooms from many generations. I have photos, my grandfather's old lottery tickets, passports and his farmer’s manuals. Bringing that into the physical world was really nice. The website was an interesting limitation. We thought everything there would be physically scanned. We like to see it as a virtual museum—it is also the objects that make up this weird, disparate universe of SAB KUCH MIL GAYA MUJHE VOL. 1 that you can explore. If you click an object, you can save the image—a few people took it and designed their own posters and other random things as fan fiction. Since we are all fans of physical media, it is nice to offer something that people can actually interact with.

KS: And with this kitsch element too, I love going to a lot of Indian carnivals, so even the album cover, when you go to the melas (fairs), there is always this one photographer there who has these old ’90s aesthetic painted backdrops or you pose with a giant tiger. The mela is a place where people come to watch spectacles, and we are constantly watching a political spectacle in the news or Dusshera events, Ram Leela events—recounting our history, mythical tales and so on. The aesthetic of these spectacles is purely in the realm of kitsch.

Still from 'OFF DUTY'.

UD: There is a moment in your short film OFF DUTY where the policeman sticks an image of Sidhu Moose Wala on his bike. In Sidhu’s music video for “Sanju,” he used a lot of video footage and newspaper prints from when Sanjay Dutt was arrested. Its video format is also created like a phone, anticipating how it will be watched—it is a bit similar to the way you are thinking of visual formats—do you take from him?

KS: Sidhu is a very important icon for Punjabis. I remember before Sidhu passed away, there was this general sentiment in Delhi—not everybody was into Sidhu, even me included. It was only after he died that all of us were listening to him and realised a lot of his stuff is deeply politically charged as are the circumstances around his death. Since Chamkila, there had been no shootout for a big musician. I have travelled to Sidhu’s village, Mansa, where I am shooting a separate documentary about the drug crisis in Punjab. Every home, car, canteen and coffee shop—wherever you are going, Sidhu is present throughout Punjab. I think he represents this hypermasculine nature of Punjabis but, also, because he made it. He has a song called “Tibbeyan Da Putt.” Tibbeyans in Punjabi are places which are almost barren. He says that “I come from a place that is not very fertile.” Right now Punjabis are having a moment on the global stage, with AP Dhillon playing international shows and collaborating with international hip hop artists and with Diljit playing Coachella. But honestly, Sidhu opened up the floor for Punjabi music in many ways by incorporating folk melodies and tunes into a hip-hop rap structure and by building an audience. The image of Sidhu in the Thar, which is the symbolic car for Punjabis—I incorporated some of those elements in “CTRL DEL ALT.” Like “the weight of history on your shoulders and no one can hear you cry in your Mahindra Thar”—that was the car that Sidhu was shot in.

UD: Have you ever faced any opposition while performing?

SV: Not yet, but there was a very funny moment at Serendipity. We were on stage, and when I looked to the left of the stage as the hard songs were about to drop, I saw that there were two cops. The next song we were going to play was “POLICE STATE 2020.” I asked Rounak, “Should we not?” Rounak said, “I don't give a fuck.” I once left the stage while the song was dropping, and they were filming it—they were enjoying it. Sabu has a video from the front of the stage where he was filming these two cops.

KS: Before we go on stage, I certainly worry about this every time. I feel a lot of the Punjabi lyrics—because we are playing in, say, Maharashtra—are going over a lot of people's heads. We have not played a show in Punjab yet. A lot of people are listening to the music without any sense of context, but they know there is some political tone to it. I think we like being in that weird little space where people may just take in the music—a lot of the music works as sort of this Trojan horse.

RM: As a group we are not political commentators or activists. There are other people who are doing far more impactful work in that space. But, at the very least, considering the state of things, we try to not just criticise it but subvert it and make fun of the absurdity of the situation that is happening. The chaos of all the news and the information we deal with is so deeply absurd that it can make you angry but also cry and laugh. “POLICE STATE 2020” is a critique of police brutality but it also makes fun of the idea of authority and these guys in police uniforms who think they have done something great just by putting on a uniform. The video was to just show how absurd and ridiculous the whole idea of being policed is in and of itself. And that is why EXCISE is in that vague space. I do not think anybody can say with full authority that “These guys are on stage saying anti-India things” because we are not actually saying that. The idea is to be in that space of satirising but playing and having fun with it while avoiding any kind of accusation of actually speaking truth to power. Because we are not really doing that. We are doing something else entirely which is always confounding the person who is watching the content. Because the people who know, they know. For people like a mantriji (minister) or a cop, the desired effect is for them to watch this and be utterly confused by it. I do not want the cop to be angry and unplug the system. I want them to enjoy it and then later be like, “Oh wait, what?”

In case you missed the previous parts of this interview, read them here and here.

Still from LIFE'S A GAME'.

To learn more about defining visual moments from the 1980s and 1990s, read Arushi Vats’ essay on the exhibition and catalogue The Sahmat Collective: Art and Activism in India since 1989, Prabhakar Duwarah’s essay on Prashant Panjiar’s exhibition and book That Which is Unseen and Ankan Kazi’s review of R. Srivatsan’s book Conditions of Visibility.

All images courtesy of EXCISE DEPT.