Staging the Farce: The Visuality of EXCISE DEPT

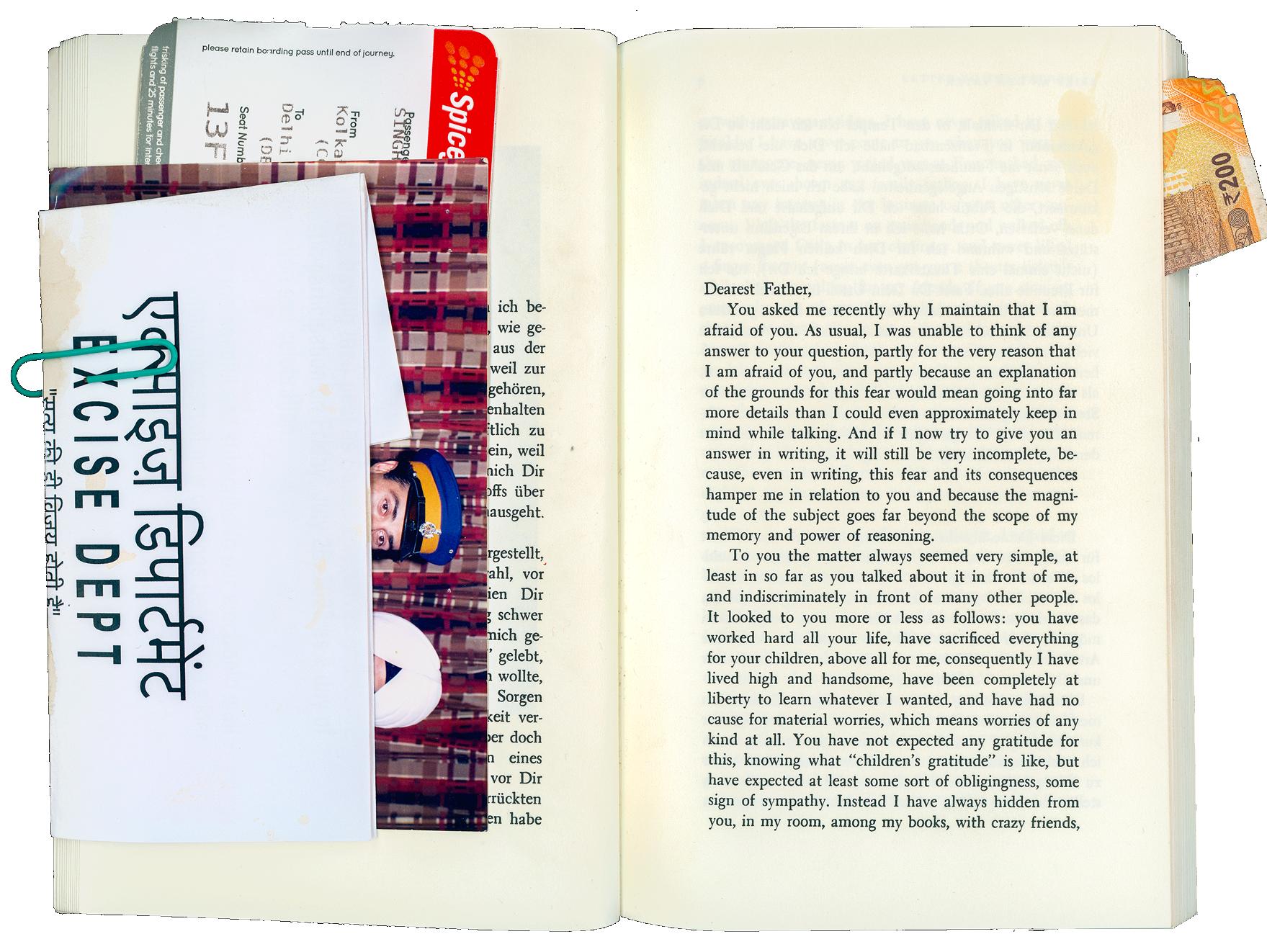

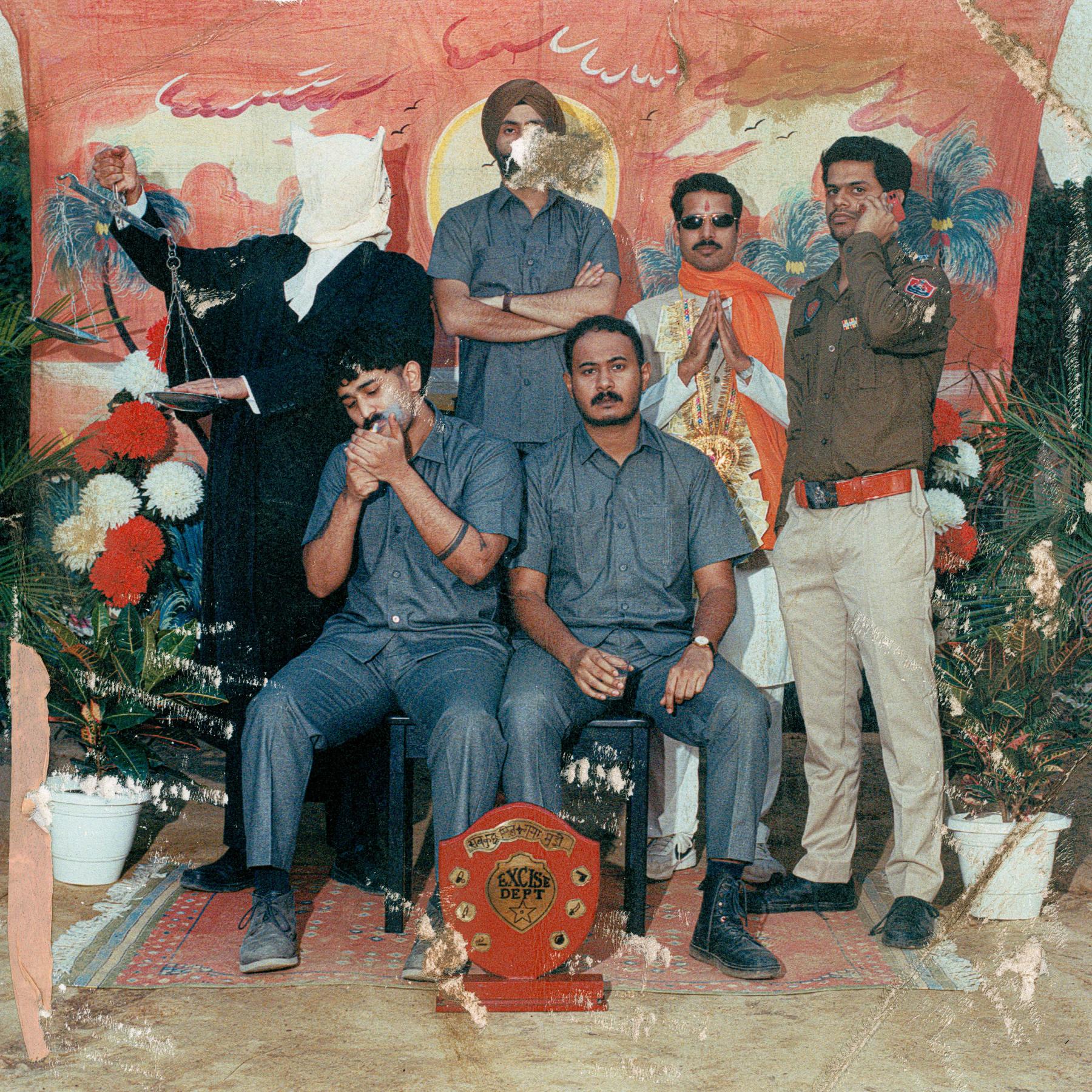

Drawing from a range of personal video and photography archives as well as everyday motifs of Indian kitsch from the early 1980s and 1990s, EXCISE DEPT’s music videos are overpowering in their visuality. In the first part of the interview, the collective—consisting of Karanjit Singh, Rounak Maiti, Siddhant Vetekar and Andrew Sabu—discussed how they imagine themselves as four state karamcharis (bureaucrats) gone rogue. With “Government-core” as the essence, they uncover narratives left behind in the larger telling of Indian history and culture, particularly regions like Punjab and Bengal. In the second part of this interview, the members delve into the references behind EXCISE DEPT’s striking visual language.

Still from 'POLICE STATE'.

Upasana Das (UD): Your visual experimentations take from WhatsApp forwards and Instagram reels. I noticed the 1990s and early 2000s Shemaroo logo we would find on film CDs in some songs, so you have taken from films from that era too. It is, in general, a very ’90s experimental video-making aesthetic, with too many things on your screen, colours and the beginning of digital manipulation. What made you want to work with this format?

Karanjit Singh (KS): I have a pretty extensive archive of old taped interviews and news recordings in my family, for some reason. I was always trying to find an outlet for these and, coming from documentary, to add a little of that element too. So, the first video that we put out “EAT AN AAM” was something I was working on way before EXCISE started—on Sikh masculinity and the Punjab police. I went to the Punjab Police training grounds to film them. It never ended up being anything because, when I showed up, they had been told that this documentary person was coming. It was a holiday for them, but they made all the trainees reenact their training process. And they did not want to do it—I could tell they were tired on their day off. When I was filming, they kept putting super fit Punjab police officers in front of me. It just felt so staged, and so it never ended up being a documentary. But EXCISE is the place where I felt this farce-ness of it all—and how police people train each other—could really shine. With the archives, there is so much material. Sometimes even when we make music, we just put on these news recordings and make music to that.

Rounak Maiti (RM): Because KJ’s (Karanjit) background is in images, the image starts to emerge simultaneously as the songs are also made. Everything is being born together as one cohesive unit—that was the impetus behind the website as well, to give the album a visual identity and to engage with our listeners in a visual and tactile manner. Even with the cassette now, which is the first physical thing we have done, we were thinking about ways to consume and build a connection with music that goes beyond listening on Spotify. The website was the first time we played with the idea of interactivity—all of us are very interested in interactive gaming experiences.

Still from EXCISE DEPT's interactive website.

KS: That is definitely something we want to delve deeper in the future. There is a game that I had grown up with called Yodha: the Warrior that came out in the early 2000s right after the Kargil War. It is this character just killing a bunch of Pakistanis. Its dialogues were very Bollywood driven—‘Bharat Mata ki Jay!’ (Hail Mother India!)—all of that stuff. It is a game that has been completely lost to time, and Maiti and I have been trying to find it and do something with it. We found this person in North Delhi, at this book market, from whom I sourced Bandi’s old news magazines. I gave him a time period of ’84 to ’94—that was the decade we were trying to target deriving the aesthetic from. So, a lot of those images come from those magazines. A lot of the things on the website are all things Rounak and I had collected over the years when we used to live together. There is a sense of coming across a physical archive and the beauty of going through these old magazines—we did that for a month. When you try to learn about history through these magazines, you see that there are so many things that have been left by the wayside. So, hopefully, the next kind of era of EXCISE will target the next decade—from the 1990s to 2004, maybe. Why we chose ’84 to ’94 is—especially with the themes of the album too—because I feel it is an interesting mirror image of where we are at right now. A lot of the trends that are emerging politically in the country now started around then—this idea of the nation, states trying their own failed secessionist movements, the BJP on the rise, the Rath Yatra happening, the demolition of the Babri Masjid, etc. And in these magazines, the Congress party, which was in power over the course of that decade, are struggling to hold on to power—they now need to rely on coalitions. It is where we are at right now with our current government. But at that time, Reliance was just coming up as this new tech firm. They placed ads in these magazines like “Watch out for the new players in town”—that was how they were phrasing their language—and look where we are today.

RM: There was a weird sense of optimism also in this year, and you really see it in print—so much of the writing is quite optimistic. The website captures that moment in time. This was an era when a lot of new technology was coming into India; people were buying phones, televisions and cars. There was also some cultural optimism. There was also globalisation happening. It was a very odd cultural era actually and it speaks a lot to what we have done on the album—the feeling of vague optimism, but also there is something brewing under it, which is clearly not very optimistic. But there is also a sense of collective hope and some kind of euphoria. It is confusing, right? That confusion is something that we have tried to kind of capture.

UD: Your archive sounds quite extensive. Karanjit, how diverse is the footage?

Still from EXCISE DEPT's interactive website.

KS: A lot of the footage that I have is from Punjab—the early ’90s political happenings and campaigns. My family is kind of Congress adjacent, so we just happened to have all these random tapes of rallies during Narasimha Rao’s era and Rajiv Gandhi’s era. A lot of these rallies are very strange because the members and supporters of the Congress Party are wearing shorts, which look like RSS shorts. They are taking oaths to the flame, which is very strange to see. Three years back, I went to all of my family members and collected all black-and-white photographs that I could get my hands on. Rounak was also digging out a bunch of his archives—old analogue photography is something that we keep coming back to in the EXCISE aesthetic and play with that kind of print. We scan the photograph, then we print it. We then cut out pieces from the photograph, scan that and create video and photo collages from it. So, everything is coming back into this analogue format; we are trying to move away from the digital medium.

UD: In the visuals, it is interesting how you move between Bengal, Punjab and Mumbai—was the “BAARO MAALA” video documenting the bahurupee performers in Bengal?

KS: I have been filming a lot of Ram Leelas and sehra bandi events in and around Punjab and Delhi. The beginning and the end are from Punjab and Delhi, while the middle part with the main dancer was shot in Lodhi Colony. A friend and I were just walking by on Vishwakarma day, and they had an event on. There were local political leaders on stage who were just watching this insane performance of somebody dressed as Shiva and smoking ganja on stage and going absolutely ham. So, I just started filming. We did not even intend for it to turn into the “BAARO MAALA” music video.

UD: It was interesting how the video was pausing towards the end, similar to the buffering one experienced in the ’90s when you had a faulty CD.

KS: I personally do not like the digital medium; it is too sterile. So, using a VHS aesthetic, glitching out the video and not giving it that clean look is what we want. We want the dust and scratches. Coming from a documentary field, sending stuff to newspapers, you have to correct for every speck of dust. Film as a medium is not like that—you never know what you are going to get with tapes which deteriorate over time. I love the term generation loss. Things are lost to time, and in many ways, EXCISE DEPT’s job is to try and find these lost objects and artefacts. So even if it is something that we filmed now, sometimes we just give a feel to it as if it were something from an archive.

SAB KUCH MIL GAYA MUJHE VOL. 1 album cover.

UD: The line “SAB KUCH MIL GAYA MUJHE VOL. 1” (I Have Everything I’ve Ever Wanted) has been there from your first single and has accrued meaning throughout your releases over the years. What film is the line from?

RM: All I remember is that it is a Sunny Deol film! When Sid, KJ and I were initially starting to make music, we were watching a lot of Bollywood and pulling cool sound effects and dialogues. Sid and I were sampling a lot of background (BG) scores, which often tend to be overlooked as part of the film’s sonic identity. Very rarely was it the case that the BG score would be printed though there were exceptions. For instance, for Satyajit Ray, the score would get printed as vinyl or cassettes. It was the same for certain Hindi films like Mughal-e-Azam, but for a lot of these ’80s and ’90s films, it only exists in the film. Bollywood has been a huge palette to pull from and be constantly entertained by. I think there are only a few spots on the album where we have pulled dialogues. We just liked how SAB KUCH MIL GAYA MUJHE VOL. 1 sounded. It was actually Sabu's idea to call the album SAB KUCH MIL GAYA MUJHE VOL. 1. Then, over time, because it is a very identifiable part of every track, it fed back into this general philosophy of self-determination and a euphoric call to action and collective work ethos. I think it is a good principle for us as individuals to live with, to act from this place of self-assurance that we have everything we need, and as a group also, most of us are pretty much self-taught with whatever we do. We are self-funded, so we have done everything independently—the music, the videos, the touring and so on. I think that this phrase encapsulates that really nicely.

UD: There was another interesting line in “Ami Jaani” where a police officer says that it is work he does not want to do but, if he does not do it, there will be someone else who will.

Still from their Film 'OFF DUTY'.

RM: KJ had found this video about this guy who lives a very normal life. He was getting up in the morning and getting ready to go to work like anybody else. Then it is revealed that he is not only an executioner but he also fixes the rope for hangings. He is talking about absorbing the guilt of what the fuck he is doing—how he stays up at night. He is full of anxiety because he does not know why he has to do this. But at the same time, there is this moral obligation; someone chimes in and says, “Oh, but you know, these kinds of heinous crimes, unko saja milnihi chahiye (they should receive punishment), and because we are not punishing them, that is why all the murder rates are going up.” He is struggling to speak Hindi, but he is also struggling to express this very complicated emotion. He is actually quite torn up about it, but as is the case with India, repression max. So by the end, he is like, “Okay, but you know, someone has to do it.” I think it was funny for us because it is just that we, as a group, are doing the dirty work.

In case you missed the first part of the interview, you can read it here.

To learn more about music as a form of protest, read Upasana Das’ essay on Poulomi Desai’s practice and conversation with Shahbano Farid’s on her film Karachi at Night (2024). Also read Silpa Mukherjee’s essay on Bollywood’s tryst with orchestra music in the 1980s.

All images courtesy of EXCISE DEPT.