The Afterlives of G. Aravindan's Thamp̄: Parallel Cinema and Spectatorship

In December last year, the film programme Rewriting the Rules screened a series of films from Indian Parallel Cinema produced between 1970 and 1990 at the Barbican Centre in London, as part of the centre’s landmark exhibition The Imaginary Institution of India. Curated by Shanay Jhaveri, the newly-appointed Head of Visual Arts at the Barbican, the exhibition featured artworks from 1975–98, largely defined by Indira Gandhi's declaration of the state of Emergency through the 1992 Babri Masjid demolition and finally to the series of five underground nuclear tests in the Pokhran desert of Rajasthan in 1998 that led to major economic sanctions for India alongside marking its entry among the ranks of existing global nuclear powers.

Curated by film scholar Omar Ahmed, the experimental film programme highlighted how Indian Parallel Cinema, which had roots in the 1950s and came of age in the late 1960s, engaged with themes of land reform, urbanisation and the experiences of marginalised communities. The programme featured films by notable directors, such as Mrinal Sen, Mani Kaul, John Abraham, Mira Nair and the Yugantar Film Collective. In this article, I examine Govindan Aravindan’s Malayalam film Thamp̄ (The Circus Tent, 1978).

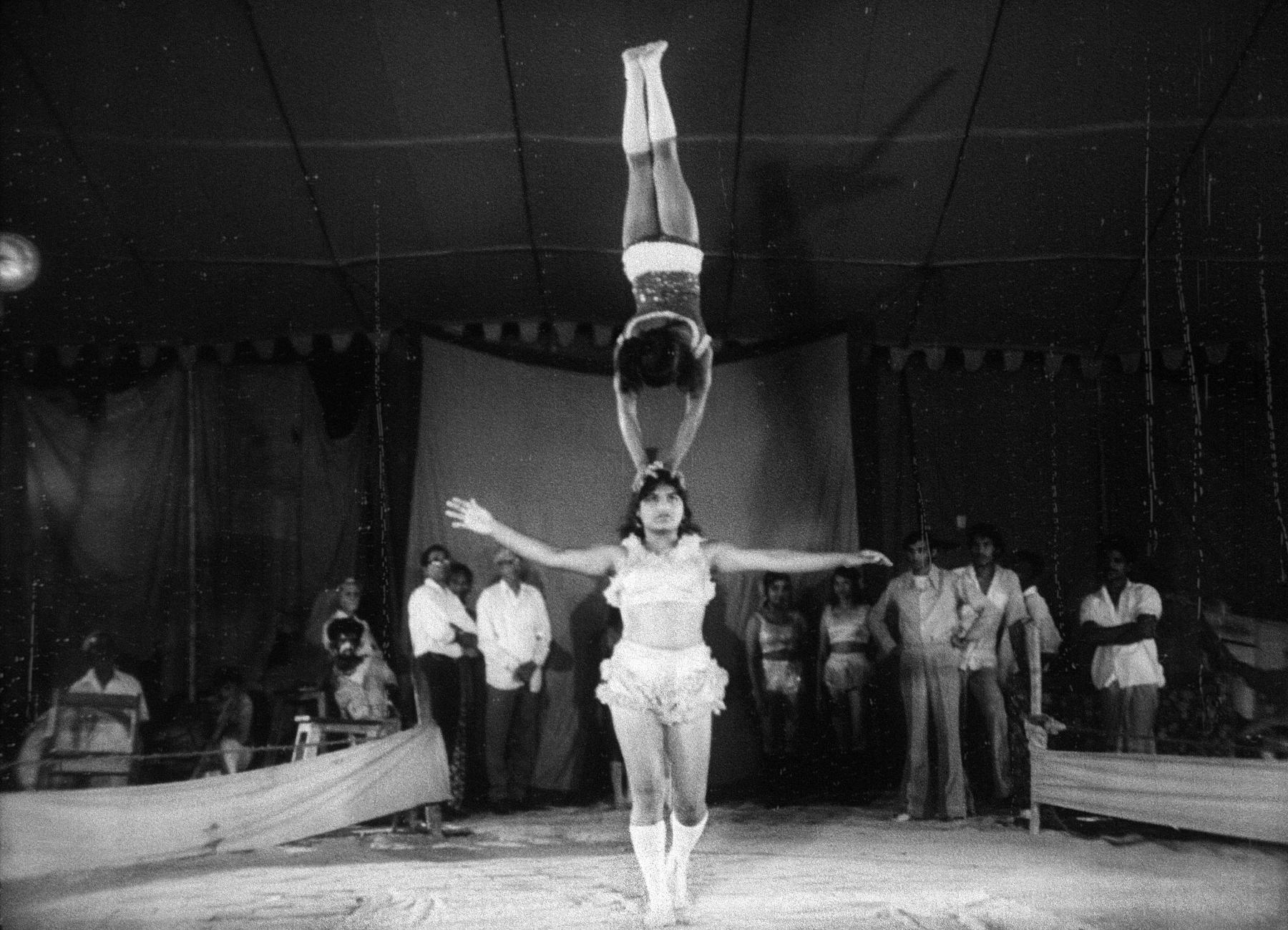

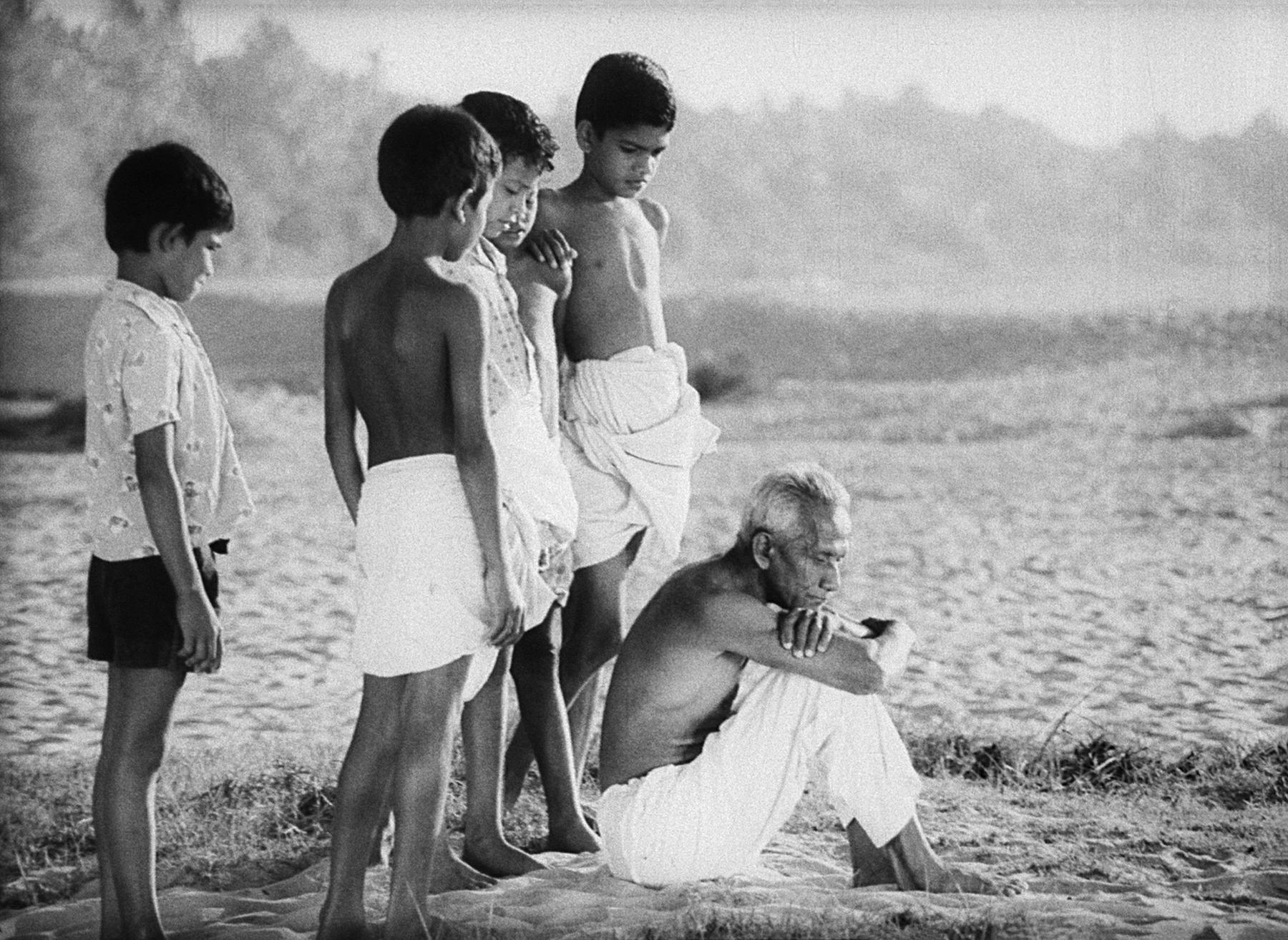

Thamp̄ is a part-fictional observational documentary film following a travelling circus across a small coastal village of Thirunavaya, located at the banks of the Bharathapuzha River in Kerala. Here, Aravindan sets the stage for a real-life encounter between members of the travelling circus troupe and villagers who have never witnessed a circus performance before. The film begins with trucks of the Great Chithra Circus entering the village and pitching their tents on the riverbank while distributing leaflets in the village for two daily performances. On the third day the circus coincides with the local temple festival, which causes the villagers to lose interest in the shows. The circus troupe then proceeds to exit the village, and the musically inclined son of the local feudal lord Menon decides to leave his hometown and join the troupe.

With its sparse dialogues and fluid form, this experimental docufiction does not follow a linear narrative structure. Aravindan calls it his “location film” that was made without a script to capture the villagers’ response to the circus performance. At first, the villagers are aware of the presence of the film crew and cameras filming them viewing the show, but once the acts begin, the crew manages to capture an audience completely enthralled by the performances. This viewing of the spectacle resembles Giuseppe Tornatore’s Cinema Paradiso (1988) which captures candid moments of audience enchantment as residents of a small Sicilian village, including children, attend a film screening for the first time.

Thamp̄ has the quality of anthropological research conducted in rural Kerala, as it documents temple festivals and rituals while also portraying the everyday life of people living on the Malabar coast. In Aravindan’s film, the circus and its controlled setting of repetitive performances is masterfully juxtaposed against the ephemerality and liveness of the ritual dance performed at the temple grounds during the local village festival. The images meander through morning rehearsals of the cycle acrobats and gymnasts and settle on the candour of the villagers first encounter with the circus at sunset.

With Cinema Paradiso, the audience response to the enchantment of viewing celluloid images for the first time simultaneously underscores the alluring and democratising force of cinema—its power to organise collectivity through shared viewership and disseminate ideologies among the masses. In Thamp̄, Aravindan links the enchantment of cinema to other pre-existing forms of spectatorship such as the carnival, the circus, the seasonal festival and the ritual performance. The film contrasts the audience's passive reception of the circus with the lively communal spirit evoked by the ritual dance at the local temple festival.

The original title of Aravindan’s film, Thamp̄, translates from Malayalam as “the tent.” Taking its cue from the title, the visuals of the film developed by cinematographer Shaji Karun focus on the billowing umbra of canvas tents fluttering under the coastal canopy, alongside exquisite black-and-white footage of the silver filigree of light seeping in through the alcoves of an ancient banyan tree. As the acrobats and stunt-cyclists practise their repertoires under the circus tent, elsewhere in the village, the young musician and mystic rehearse their songs under the shade of the banyan tree. One is lulled into a hypnosis of monochromatic calm, bringing to mind a more recent film 1956, Central Travancore (2019), directed by Don Palathara, with its diegetic soundscape of insects trilling at night and the patter of rain falling on banana leaves in the high-range forests of Kerala.

In the 1970s, regional films made by arthouse directors were attributed to the emergence of film society movements in India—directors like Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, Ritwik Ghatak, Shyam Benegal and Kumar Shahani were forging an alternate paradigm for cultural aesthetics through parallel cinema, as they were highly critical of the existent socio-economic and political views shaping the nascent postcolonial state. Aravindan, along with Adoor Gopalakrishnan, pioneered the film society movement in Kerala that was instrumental in evoking social consciousness in the post-independence era.

Compared to regional cinema produced in other states, the new wave of Malayalam cinema belonging to the same period were singular in their representation of social realism using melodrama, which highlighted the intersection of caste and class hierarchies. Aravindan explained his political alignments in an interview where he states that “the real movement is not in the cities, it is in small towns and villages.” In Thamp̄, the injunction of feudalism and postcolonial capitalism is represented through the character of the landlord Bindi Menon, who has returned with capital gains from his ventures in Malaysia. While Menon continues the legacy of exploiting workers at the factory and women within the household, his spiritually inclined son is eager to escape the patriarch and finally leaves the village with the circus troupe.

Thamp̄ has only recently been revived from the archives and contends to be one of the exemplary films representing parallel cinema from 1970s India. It premiered at the Cannes Film Festival a few years ago after it was restored in 4K from its original 35mm print at the National Film Archives of India (NFAI) with the support of the Film Heritage Foundation in collaboration with Martin Scorsese’s Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, and Cineteca Bologna.

To learn more about parallel cinema in India, read Kshiraja’s essay on John Abraham’s Amma Ariyan (1986) and Sucheta Chakraborty’s reflections on the restoration of Shyam Benegal’s Manthan (1976) as well as Ankan Kazi’s piece on the role of filmmaking collectives in India.

All images are stills from Thamp̄ (The Circus Tent, 1978) by Govindan Aravindan. Images courtesy of the Barbican Cinema, Rewriting the Rules: Pioneering Indian Cinema after 1970.