Imagining Palestinian Statehood: Arabfuturism and the Scope of Radical Fictions

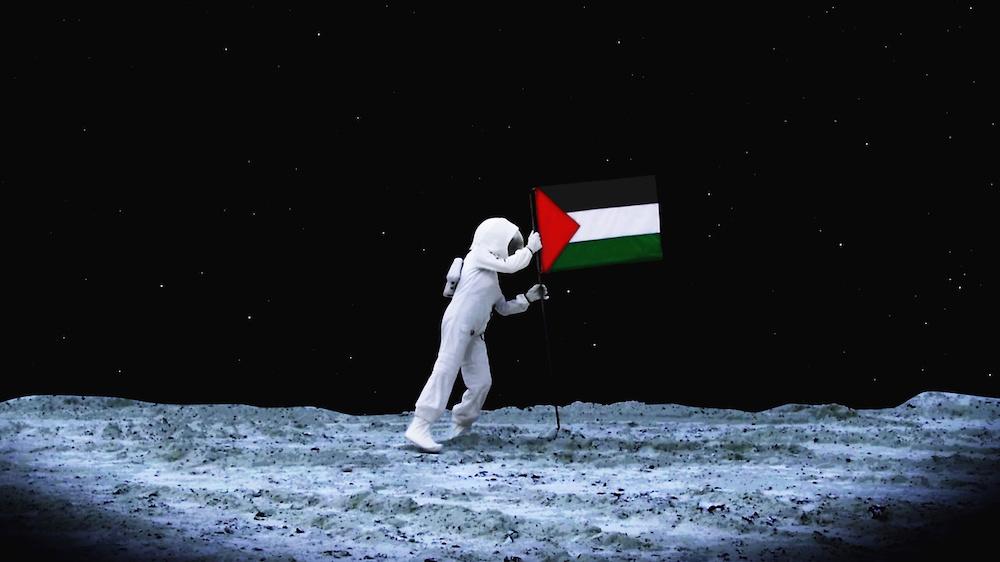

The narrative of triumph around the moon-landing is reserved for the white male body in historical memory, which is substituted here with a female Palestinian body in a radical revision of settler-colonial history. (A Space Exodus. 2009.)

In this second part of a series studying image politics in Palestinian films, we will be examining the idea of Arabfuturism in the works screened at “For a Free Palestine: Films by Palestinian Women” by Another Screen.

Coined by Jordanian artist Sulaïman Majali, the term “Arabfuturism” refers to the anticipation of a future beyond the hegemonic, Eurocentric representations of the pan-Arab world. In the specific context of Palestine, Arabfuturism and its mode of operation—science fiction—invites not only a rewriting of Oriental narrativisation, but also an exploration of Palestinian selfhood outside a life defined by persistent trauma. Primarily the domain of diasporic expression, Arabfuturism creates speculative futures as a flight from imperial definitions of identity. Like its progenitor, Afrofuturism, Arabfuturism emerges from the understanding that the apocalypse has already happened (as opposed to white tropes of science fiction where the narrative is geared towards one). Speculative fiction, then, opens up—for the dispossessed body—space for forms of fabulation that carry the potential for significant epistemological shifts. Although she has denied a conscious identification with Arabfuturism owing to its constantly evolving definitions, Larissa Sansour has emerged as an important filmmaker imagining models of Palestinian statehood—whose future in actuality is either prescribed or foreclosed.

Could the Palestinian body be a refugee still, only in outer space? (A Space Exodus. 2009.)

Sansour takes the premise of the moon-landing—a historical event from 1969 that has survived through imaginative iterations in popular culture—to create A Space Exodus (2009). In this film, she performs the planting of a Palestinian flag on the surface of the moon, while a disembodied voice declares, “One small step for a Palestinian, a giant leap for mankind.” The film draws its visual syntax from Stanley Kubrick’s influential work, 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), and reconfigures it in the Palestinian political context, where a body from the margin occupies the image and enacts the event. Astronauts, spaceships and intergalactic travel have historically been markers of white expansionist ambitions. Their appropriation by Sansour on film dislocates the colonial context of the Space Race to rethink Palestinian subjectivity through a supremely utopian lens. As writer and researcher Lama Suleiman points out, the premise also leads one to imagine a possible case of expulsion of the Palestinian body out into space because it could not be accommodated on earth. In this case, the triumphalist legacy of the event gives way to a grim future of seeking refuge in outer space. Thus, it effectively draws our attention to the genre’s underlying conflict with the perimeters of hyperbolic imagination.

Growing the cherished olive in the interiors of Nation Estate; the tree serves as a symbol and object of remembrance from Palestinian life on land. (Nation Estate. 2012.)

The building re-enacts historical landmarks such as the al-Aqsa mosque on the floor of Jerusalem city, which thus acquires the character of an artefact in a sterile scape akin to a museum. (Nation Estate. 2012.)

Back on earth, Sansour explores Palestinian statehood through the imagination of a colossal skyscraper that houses entire Palestinian cities and their inhabitants. In Nation Estate (2012), the compression of the Palestinian peoples into one building through the erasure of horizontal land proffers a vertical solution to the problem of occupation. Each city has its own floor, and intercity trips previously disabled by military checkpoints are now accomplished through elevator rides. The intended irony of “living the high life” in atomised pockets is revealed in the relegation of Palestinian bodies to a high-rise monument in literal separation through the Apartheid Wall that lines its circumference. Markers of Palestinian life are conveniently condensed into symbols as residents saunter through simulations of open landscapes indoors, creating an anxiety around the visible absence of community. The Palestinian identity is no longer located in shared trauma, but a denial of ancestral history through its relegation to the status of an artefact; it is a utopia rooted in amnesia.

In a playful re-enactment of Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper, Sansour uses the fictitious trademark of porcelain to accord Palestinian statehood equal status at the table with other, more visible histories. (In The Future They Ate From the Finest Porcelain. 2016.)

Going deeper into the earth, Sansour explores archaeological militancy as a tool of contemporary warfare in the film, In the Future They Ate from the Finest Porcelain (2016). A group of “narrative terrorists” makes underground deposits of superlative porcelain—its age manipulated through chemical maneuvers—in the hope that these objects will be discovered by future archaeologists. Carrying the mark of the keffiyeh (symbolic of Palestinian nationalism), the aim of the porcelain is to make claims to the population’s vanishing lands in a future that will validate their presence, orchestrating a myth around nationhood through historical intervention. In a reversal of settler-colonial extraction and erasure, the film uses archaeology and archives—tools of imperial knowledge production—to reconfigure history through deliberate falsification as an act of reclamation in absentia.

At one point, the film features a heavy downpour of porcelain—an apocalypse of “ceramic rain” that is likened to the Biblical plague. (In The Future They Ate From the Finest Porcelain. 2016.)

Arabfuturism thus makes use of science fiction to not only create self-determined representations, but also dislodge its extant parameters to create impossible futures in light of the lived genealogies of marginalisation. In its foregrounding of the histories of the vulnerable, Arabfuturism has affinities with Indigenous Futurisms as they confront colonial ramifications through reimaginations of tribal sovereignty. Subash Thebe Limbu has talked about Adivasi Futurism in the South Asian context. Here, the discourses of indigeneity, technology and modernity intersect in the common drive towards dismantling Brahmanical patriarchy and casteism that have been historically detrimental to the existence of Adivasis. Arabfuturism partakes in the radical fictionality that issues from indigenous struggles. It assembles speculative narratives that cumulatively counter the colonial archive through the virtual, the anticipatory and the future conditional. In the context of Sansour’s work, it imparts the notion of Palestinian statehood a performative veracity.

To read the final part in this series, please click here.

All works by Larissa Sansour. Images courtesy of the artist and Another Screen.