Forensic Time and Territorial Dislocations: Exploring the Trauma of Exile through Google Earth

This is the first of a three-part series studying image politics in Palestinian films that were available for public viewing from 18 May to 21 June 2021, on Another Screen, the streaming arm of the United Kingdom-based feminist journal, Another Gaze. This programme was part of “For A Free Palestine: Films by Palestinian Women,” curated by Daniella Shreir.

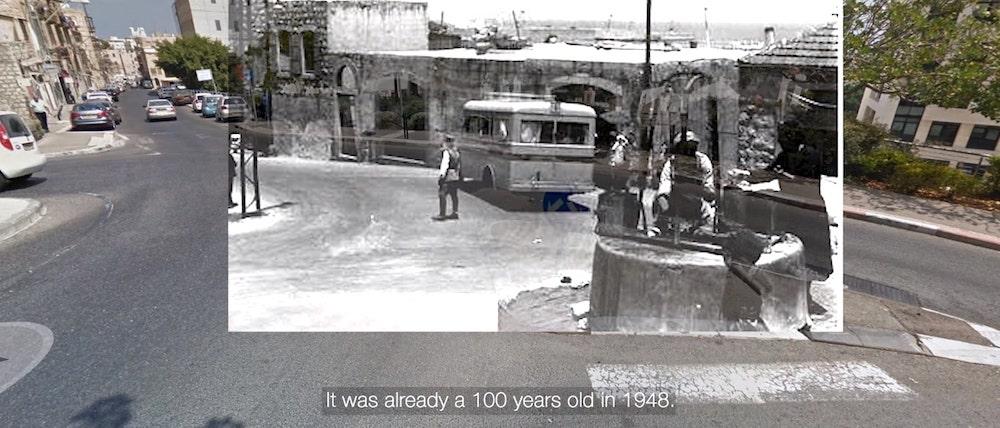

Temporal juxtapositions are activated through placement of twentieth-century photographs on a Google Street View of Haifa. (Your Father Was Born 100 Years Old, and So Was the Nakba. 2017.)

In Forensic Architecture, Eyal Weizman writes that the digital image is essentially composed of a grid constituting pixels: "This grid filters reality like a sieve or a fishing net. Objects larger than the grid are captured and retained. Smaller ones pass through and disappear." This partial illegibility applies to satellite photography, especially of conflict zones. Google Earth and other public mapping software often take the liberty of redrawing territorial borders based on the user’s location—such as the former’s marking of Kashmir as a “disputed” region when seen from outside India but completely under Indian control when viewed from within. This points to Google’s flexibility of positions, which often panders to the occupying power. For instance, it does not mark illegalised areas or their access roads in Palestine, in line with the policy of the Israeli state since its establishment in 1948.

During the most recent attacks on Palestine by Israeli Defence Forces in May 2021, it was noticed internationally that the satellite imagery of these areas was degraded and therefore, inaccessible for study. The calculated obscurity of geodata—used to analyse illegal expansions and human rights violations—is an attempt at obscuring the relations between intimate images from the ground and their confirmation through aerial gaze. When not tampered with, Google Earth reveals the history of ethnic cleansing of the indigenous Palestinians through changes recorded in the topology over multiple captures.

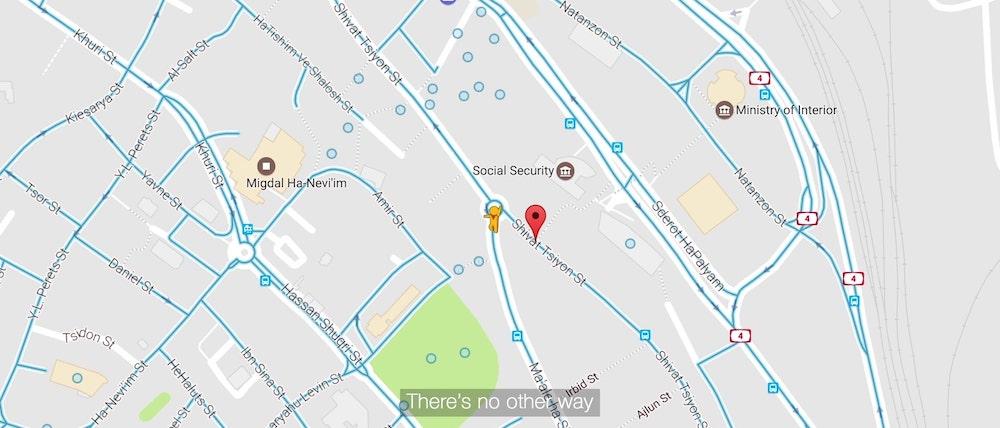

Motivated by an urgency, the disembodied voice begins her search for the homeland she knew; the virtuality of the map indexing its impossibility. (Your Father Was Born 100 Years Old, and So Was the Nakba. 2017.)

Palestinian filmmaker and media artist Razan AlSalah takes the tool of cartography and counters its imperial roots to reinterpret optical regimes of violence. Using data as image, the film, Your Father Was Born 100 Years Old, and So Was the Nakba (2017) replaces the spatial logic of domination with an earnest navigation by a dispossessed person. The spectral, disembodied voice of AlSalah’s grandmother—a Palestinian refugee in Lebanon, who was never able to return to her hometown—swims through the Google Street View images of the town of Haifa, but the streets are no longer recognisable. She wanders through cyberspace in search of her house and for her son, Ameen, who is imagined as a little boy. As the gaze shifts around the streets, the images pixelate and distort as photographs of people from before the Nakba (the mass exodus of Palestinians from their homes in 1948) are occasionally superimposed on the current streets for comparison. This acts as a discomforting reminder of the trauma of the first generation of refugees. Here, Google Street View—a colonial tool of image-making—offers an illusion of access to a “home” impossible to return to, other than through digital trespassing.

The absurdity of the search is embedded in the image. (Your Father Was Born 100 Years Old, and So Was the Nakba. 2017.)

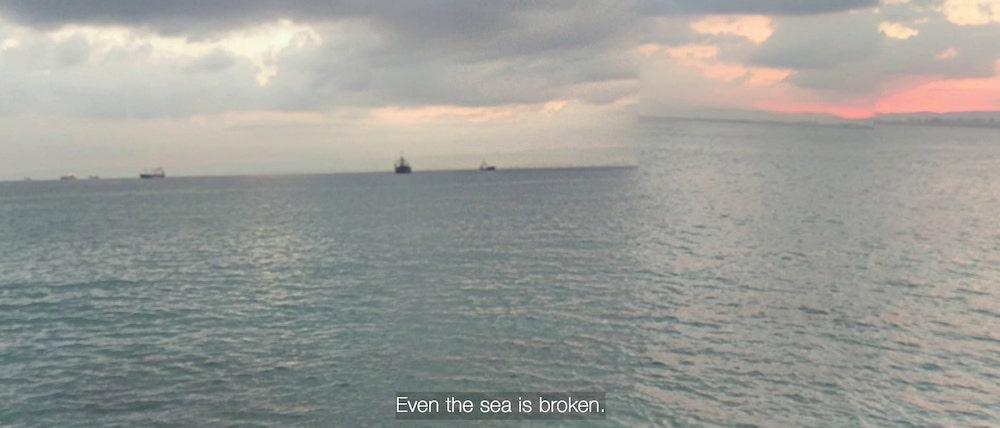

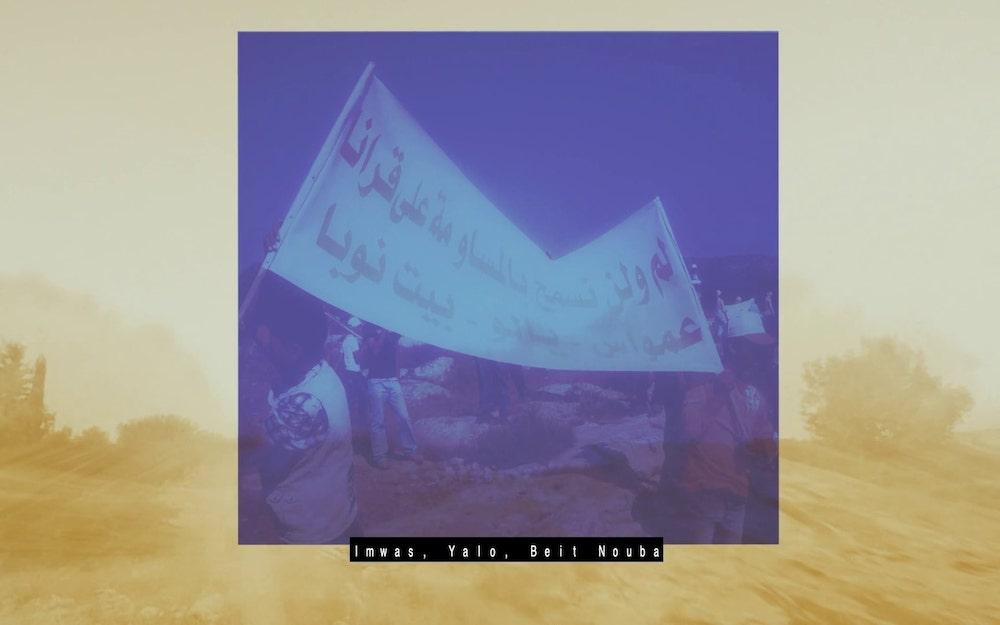

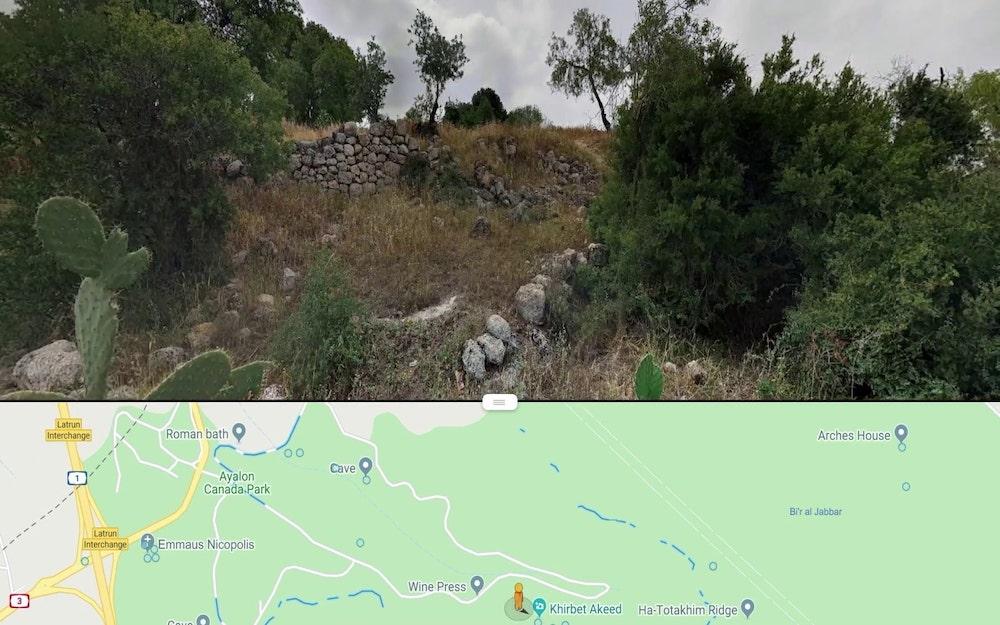

Another of AlSalah’s works, Canada Park (2020), inspects a particular event of erasure. In 1967, Israel razed Palestinian villages to the ground and undertook a project of afforestation to effectively keep the former inhabitants from returning to their land. Even in the recreational process of building a “public” park, indigenous species were replaced with fast-growing plants such as pine, which served to accelerate the erasure. The demolished villages were thus rendered invisible in the abundance of foliage. In his book, Weizman talks about how contemporary colonialism operates by covering up the traces of its own violence—by erasing the traces of its erasures. Through an experimental video essay, AlSalah explores the materiality of disappearance by overlapping Google Street View images of the park with colonial landscape photography of its former avatar (which was also a holy site). In the “greenwashed” scape of the Canada Park, she reinserts images from the unsuccessful March of Return in 2007, thus actively orchestrating a dialogue with the violence that has been invisibilised.

Canada Park—extending from no man’s land into the West Bank—as it stands after the afforestation drive. Its digital index is progressively rendered illegible in the film to reveal invisibilised histories. (Canada Park. 2020.)

Palestinian villages were erased in a strategic drive by the Israeli state to widen the Jerusalem corridor through the creation of Canada Park. The juxtaposition of the photograph from the 2007 March of Return against the current landscape indicates instances of collective resistance against institutional omission. (Canada Park. 2020.)

AlSalah uses the space of suspension afforded by Google Earth to counter the mythologies created by a militarised ethno-state—myths that have actuated the capitalist and geopolitical expansionist ambitions on Palestinian land. Appropriating a colonial tool of surveillance, the artist confronts the epistemic violence of imperial mapping by exploring the incremental violence of substitution. She uses the limitation of impenetrability in the digital sieve to visibilise fractured temporalities in the image—an act of resistance against historical appropriations of space. Using the distortions characteristic of satellite photography, the artist questions the interplay of memory and material ontology, while dissecting landscapes to visually register the events of erasure. In this translation from terrain to pixel, the earth becomes an “…embodiment of forensic time” (Weizman), its entanglements of territorial politics playing out on historical, geographical, as well as molecular scales.

Mapping Canada Park on Google Street View as it stands permanently altered through afforestation. (Canada Park. 2020.)

To read more about image-making practices using Google Street View, please click here and here.

To read the other parts in this series, please click here and here.

All works by Razan AlSalah. Images courtesy of the artist and Another Screen.