Janin, Jenin, Jenin: The Legacy of a Camp

Bakri reunites with an interviewee from his 2002 film. Screenshot from Janin, Jenin.

In July 2023, shortly after the intensive 48-hour Israeli military incursion at the Jenin refugee camp in the West Bank, Palestinian filmmaker and actor Mohammad Bakri visited the area to record the testimonies of the survivors. It eventually led to his recently completed film Janin, Jenin (2024), a sequel to his banned 2002 documentary Jenin, Jenin. In the new production, Bakri reconnects with the interviewees from the prequel, recalling the persecution he faced surrounding the controversial film, and captures witness accounts of the recent offensive upon the camp. This time, however, he was careful about not revealing the face of any Israeli Defense Force (IDF) soldier, for it was only a few seconds of a soldier’s onscreen presence in Jenin, Jenin (2002) that the military used for a defamation suit against Bakri. Though Israel’s Supreme Court overturned the immediate ban on the film in 2003, this defamation suit ultimately resulted in a permanent ban, a hefty fine and the confiscation of the work’s every available copy in 2021.

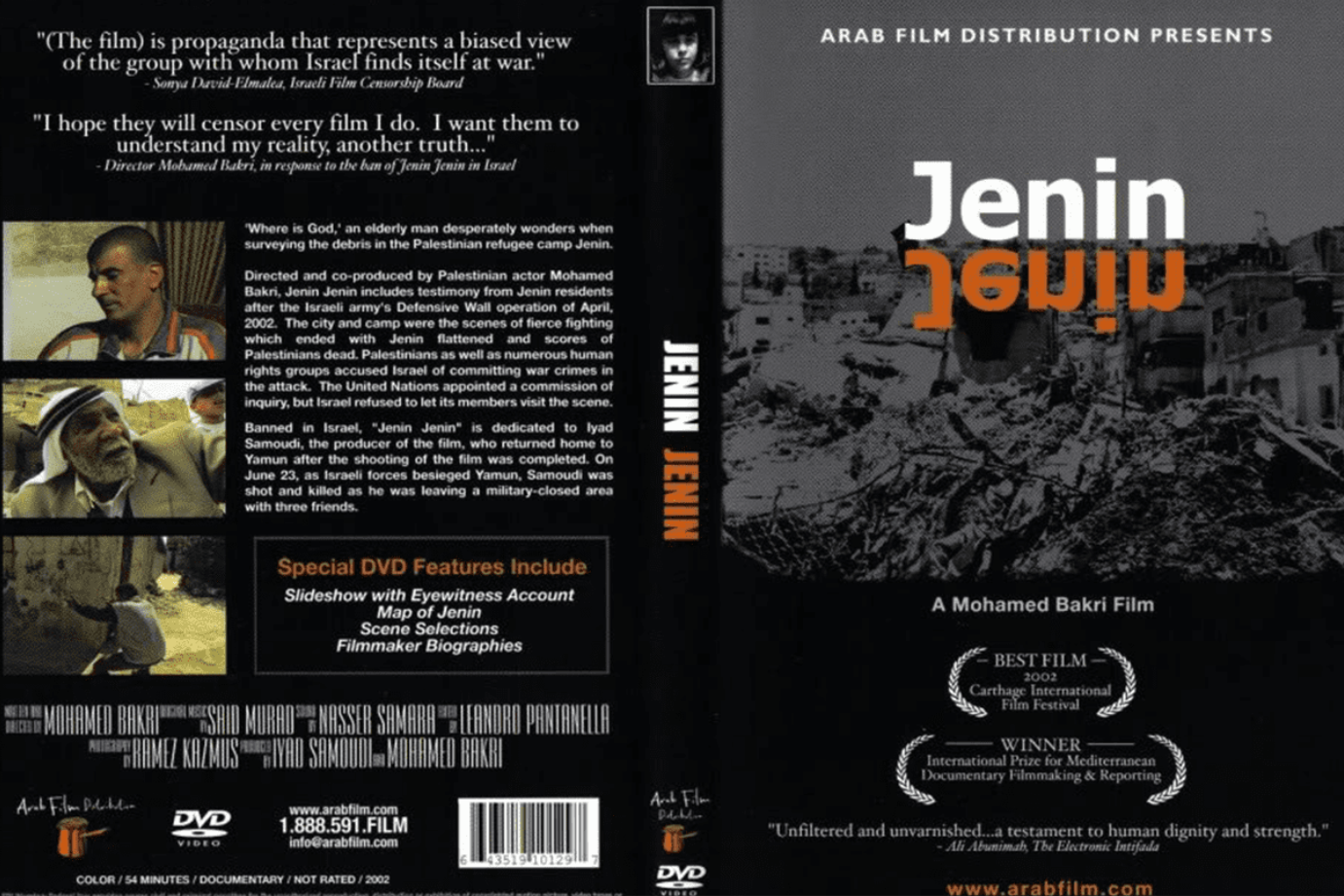

DVD Cover of the banned film.

Last August, the Israeli Police also banned Bakri’s new documentary when he tried to screen it in Jaffa’s Al-Saraya Theatre. The first word of this film, “janin (جانين),” signifies foetus or an embryonic stage in Arabic, which, according to the director, reflects the generations of resistance that the Jenin refugee camp has birthed against the ongoing Israeli occupation of the West Bank. This spirit is unforgettably reverberant in Bakri’s first cinematic record of the camp, so much so that what seemed to have distressed the IDF is not that it disclosed a soldier’s identity or recorded oral accounts of the military’s brutality but rather the interviewees’ undismayed commitment to strengthening solidarity in the camp and their resoluteness to fight back.

The young girl from Jenin, Jenin.

“The camp is our soul, our life,” claims an early-adolescent girl as she trudges through an expanse of bombarded buildings in ruin in one of the opening scenes of Jenin, Jenin. The camera captures the aftermath of the Israeli military siege of the Jenin refugee camp in 2002, which was a part of Israel’s historically notorious Operation Defensive Shield at the height of the Second Intifada (2000–05). With her keen stare addressing the interlocutor behind the camera, this young girl is one of many unforgettable characters from the documentary. She speaks at length about the steadfast morale of the people in rebuilding the camp even after endless encroachments, embodying unsparing resolve as she makes several revolutionary proclamations. In a scene that has become iconic over the years, she states, “I’d like to say something that has nothing to do with hope or anything like that. But to the Israelis, I have to say, ‘Proud as eagles, we will live. Erect as lions, we will die.’ May each Israeli bear this in mind.”

Scene from Jenin, Jenin.

The history of insurgency in Jenin dates back to a time before it was a designated “refugee camp” for Palestinians violently evicted from their land, i.e., before the foundation of the state of Israel. It was at the heart of the 1936–39 Arab Revolt in Palestine against the British Mandate authorities, prompted by the killing of the regional anti-colonial activist and religious preacher Izz ad-Din al-Qassam. Qassam struggled against the British and opposed Zionist schemes in Palestine that were encouraged by the British Mandate since its 1917 Balfour Declaration. The British responded to the uprising by blowing up a quarter of Jenin in 1938; Jenin has since become a symbol of Palestinian resistance. It came under complete Israeli occupation after the 1967 Arab-Israeli war and was one of the most targeted areas by the Israeli military during the First Intifada from 1987 to 1993. During the Second Intifada, from 2000 to 2005, the camp became the epicentre of the Palestinian armed resistance. It was primarily in response to the IDF’s aggressive onslaught on civilians in 2002 based on alleged military reports that Jenin was the “factory of suicide bombers.” Then on, resistance fighters from this community have patrolled the streets of the camp day and night to guard against unpremeditated incursions of the military.

A middle-aged Palestinian interviewee in Bakri’s 2002 documentary resoundingly highlights the camp’s legacy when he declares: “They wanted to terrorise us. Instead, they strengthened our will.” He also repeats with equanimity that “Israel is the loser, not the Palestinian people.” It is because he believes that the Palestinians can in some way rebuild everything they have lost, including their homes, lives, families, etc. But it is next to impossible to dispense with the circle of hatred and violence initiated by Israel. Even his eight-year-old son has overcome his fear of the overhead sound of military airplanes and can tell the difference between 500 and 800-calibre bullets or between M-16s, Kalashnikovs, tanks and so on. Every child in the camp, the interviewee claims, has learned to “reply with courage and confidence” when asked about the occupation.

The hearing and speech impaired interviewee from Jenin, Jenin.

A hearing- and speech-impaired young man also appears in Bakri’s film, as he takes the director around the camp to show how and where the Israeli forces murdered ordinary civilians. The camera follows him through every enactment of machine guns, fighter planes and bombings, which Bakri brings to life in the film with an overlaid soundtrack. In a synaesthetic sense, the young man’s gestures turn into sound, and the sound into evocations of horror. Bakri reunites with this young man in Janin, Jenin, whose son has joined a militant resistance group. The early-adolescent girl from the 2002 film, whom Bakri later identified as Najwa in interviews, also appears in the recent sequel—now resettled out of the camp.

Jenin, Jenin relays the torrential force of the interviewees’ indelible conviction and uncensored assertions. Their voices ring evermore loudly now, considering the Fatah-run Palestinian Authority’s (PA) recent raids in the area and its failure to win the trust of Jenin’s residents. The PA, one must remember, is the obnoxious child of the conciliatory Oslo Accords signed between the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) and the Israeli state leaders in 1993. In it, Israel acknowledged the PLO as the rightful representative body of the Palestinians, and the latter agreed to put an end to the armed struggle in exchange for a Palestinian state alongside Israel by 1999. Both agreed to establish the PA as an "interim" civil governance body over the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, with the former leader of the PLO, Yasser Arafat, as the first President of the PA. In fact, in a speech at the Palestinian Legislative Council on 15 May 2002, Arafat repudiated Palestinian resistance in Jenin, or “Jeningrad,” as he called it, after Leningrad.

However, many Palestinians, including intellectuals like Edward Said, criticised the signing of the Oslo Accords for PLO’s appeasing approach toward Israel and for surrendering the resistance movement without any concrete claim to Palestinian nationhood, reallocation of land and resources or reassurances about the curtailment of expanding Israeli settlements. The five-year Peace Process, which was supposed to follow the Oslo Accords and work toward the Two-State Solution (the formation of the independent states of Israel and Palestine), fell apart in less than two years due to recommencing rounds of Israeli encroachments. Over the years, the PA’s unpopularity among the Palestinians has also burgeoned because of administrative corruption, complete failure to protect the lives and interests of civilians as well as complicity in the Israeli occupation.

Jenin in 2002.

Several armed factions, primarily the 2021-formed Jenin Brigades, have autonomously taken up the task of defending the camp. The PA’s security operation in Jenin—its attack on the Jenin Brigades as well as its siege of the Jenin refugee camp since December last year—is a coordinated effort with Israel to crackdown on armed resistance. However, by sticking to its mandate under the fossilised Oslo Accords despite the ongoing genocide against Palestinians, it is effectively targeting Palestinian resistance and supporting Israeli occupation.

Recently, in the face of the PA’s losing control over the northern regions of the West Bank, the Israeli Army has announced plans for the complete dismantling of the Jenin, Tulkarm and Nur Shams refugee camps. This new wave of force is part of its ongoing military operation in the region that began earlier this year. Perhaps, at this point, one can only fall back upon the ordinary residents’ stern determination, moral clarity and legendary commitment to their camps. To recall the middle-aged interviewee from Bakri’s Jenin, Jenin: “We made a legend thanks to our faith and not our weapons. I swear to God. We resisted with our faith and will.”

Scene from the film.

To learn more about images chronicling the Palestinian genocide, read Asim Rafiqui’s two-part essay on his experience of being a journalist in Gaza in 2009, Santasil Mallik’s review of Against Erasure: A Photographic Memory of Palestine before the Nakba (2024) co-edited by Sandra Barrilaro and Teresa Aranguren, Kshiraja’s essay on Yousef Srouji’s film Three Promises and Ankan Kazi’s reflections on Abdallah Al-Khatib’s Little Palestine: Diary of a Siege (2021).

All images are screenshots from Jenin, Jenin (2002) unless mentioned otherwise. Images courtesy of the director.