Poulomi Desai: Race, Community and Image-Making

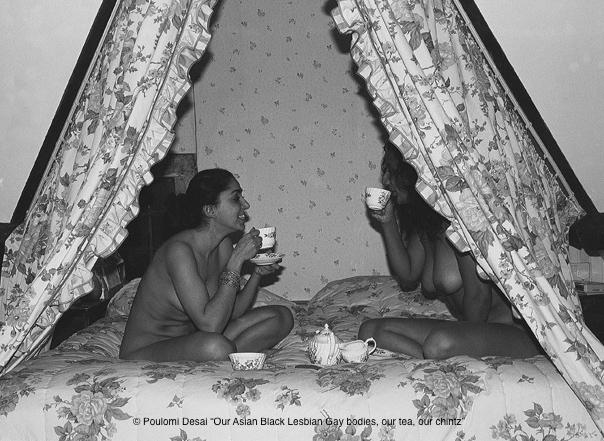

Two young girls sit on a rose-patterned chintz bed, sipping tea. Curtains of the same fabric shroud their nude forms as they smile, photographed amidst an intense conversation. One of the figures is Poulomi Desai, who shot this series as a teenager on the brink of legal adulthood, with her then partner. Part of Tate’s exhibition Women in Revolt!: Art and Activism in the UK 1970–1990, these figures playfully claim ownership over their brown, queer bodies as they indulge in ‘quintessentially British’ practices like tea drinking or buying chintz, highlighting their colonial origins. Here, Desai speaks about her artistic practice and working amidst these radical times in the UK.

From the series Our Asian Lesbian Gay Black bodies, Our Tea, Our Chintz (1989).

Desai started working at a tumultuous time in racial and feminist politics in Conservative-led UK, when, as Sutapa Biswas recalls in Shining Lights: Black Women Photographers in 1980s-90s Britain (2024), there wasn’t even another racial category beyond ‘Black’ and ‘White’. “Our understanding of ‘Black’ as a term was defined by political identification, as a way of recognising a shared collective history in terms of our coming from places that had been formerly colonised,” Biswas notes. The system was rigged negatively with various factors like underfunding for Black artists, especially women, to even showcase their work, let alone build a career—neither have many of their works received industry or academic attention.

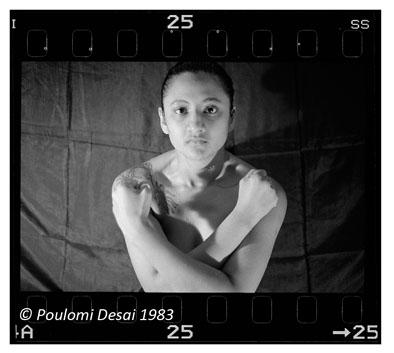

From the series Nothing Between Denial and Acceptance (1982).

Desai’s oeuvre moves between the performative and the visual—her first ‘artistic’ experience was at poetry readings, where she was taken by her politically engaged mother, where she did “rant-y” recitations inspired by punk. After moving from Hackney to Harrow—a hotbed of racist activities with the far-right group, the National Front, close to Harrow—she was on the lookout for community. She met Hardial Rai at The Commonwealth Institute, who suggested setting up an arts group in Hounslow, mentioning that activists from Southall would also join—Southall changed from being a space for the working-class white people to South Asian. So, the Hounslow Arts Cooperative Theatre (HAC) was set up. “Nearly every British-Asian actor you see on TV today—the older ones, probably passed through us at that time—like Sanjeev Bhaskar and Nina Wadia,” she said.

From the series Self Selling (1986).

Then, British TV was airing Nayi Zindagi, Naya Jeewan for immigrant Asians. “They would have ‘nice’ classical Indian music and English lessons,” she said. Desai recalled that “There were these stereotypes in TV comedy, in shows like Mind Your Language, where Asian actors and other immigrant actors who spoke like I do—or even posher—would put on false accents.” They highlighted this at HAC—through street theatre, they delved into the lives of British-Asian youth. When the late playwright Parv Bancil joined them, HAC became more professional. “When he started writing plays, we became a touring repertory,” she said, “One of our productions was a cabaret of vignettes and short sketches—we spoke about the political situation around race, sexuality and gender— that toured a lot.”

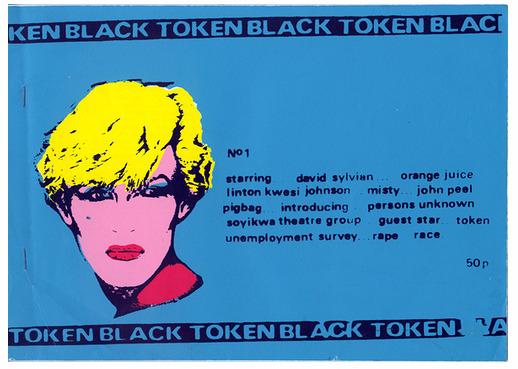

White people did not understand them and neither did Asians. They would ‘gate-crash’ weddings where she would persuade them to add their productions and events to the event roster. She said, “There were quite a few scandals… They were expecting a nice little Asian group to tell a story about a village—but we would talk about the hypocrisy of our leaders and things happening in our communities.” Leaving school at fifteen, she focused on HAC, which then had a zine titled “Token Black.” Her political performance continued with groups like the Sycophantic Sponge Bunch and a spoof metal band called ‘The Dead Jalebis’—the latter became residents at Waterman’s Arts Centre and programmed musicians like Nitin Sawhney, providing a much-needed showcase space for Black and brown artists.

Token Black zine.

In 1976, the murder of an Asian teenager in Southall propelled five Asian students to start Tara Arts. Black artists were involved in various protests during the ’80s and Desai became involved with feminist groups like Southall Black Sisters and anti-police harassment groups like the Southall Monitoring Group. Desai spoke about how they were“...literally being part of anti-fascist action. There were racist attacks and murders, and the anti-Nazi league had started up.” She recalls, “There was proper street fighting. I used to wear steel toe-cap boots.” HAC artists worked on banners as part of their creative practice, which was then taken to the streets.

Oppressive white, middle-aged men at the Chambers of Commerce were turning down business proposals by marginalised communities and assigning Black people housing in the most racist areas. A need for structural changes and wanting a place of her own led Desai to become an officer in the Race Equality Unit for the London Borough of Ealing in 1987. “We had units that looked up immigration violations by the state, we could stop discriminatory interviews… We poured money and resources into Black areas, which had always been under-resourced”, she said.

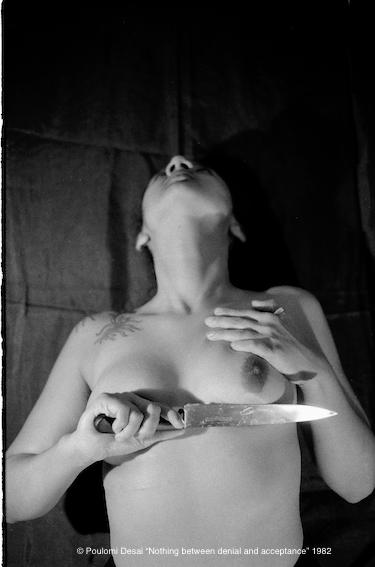

She was also exploring her sexuality and photographing her friends—which would become the series From the Coffee Table to the Kit(s)chen (1987). A little earlier, in the photo series Nothing Between Denial and Acceptance, she hides her breasts and attempts to cut them off. “I used to bind my boobs and go to clubs,” she recalled, “I presented as a man. It was a denial of the idea of being forced to be a girl, maybe.” Taous Dahmani writes in Shining Lights that Black women photographers who documented activism in the ’80s and ’90s were aware of the politics of representation: “By making their own images, Black women photographers broke the monopoly that others had over the representation of their own lives.”

From the series Nothing Between Denial and Acceptance (1982).

Programming events for gay people at the Unit led Desai to Shivananda Khan, who had set a legal precedent by getting asylum for a Pakistani gay man even after the Home Office refused it. Khan wanted to set up a South Asian gay group. Khan said she already knew people like Pratibha Parmar and Sunil Gupta. Desai asked Khan, “why don’t you set up a meeting? The first meeting was at a pub—I arranged for a grant.” SHAKTI was founded, and disco nights arranged to fund the group and because South Asian people were stopped at gay clubs and questioned. “A lot of the mainstream LGBT community then was racist,” she recalled, “We had to set up our own safe spaces—we even had Hindu priests from Leicester.” With the AIDS crisis came a new wave of discrimination as London Lighthouse, which was an HIV centre, propagated racism and Khan stepped in to help. During that time, a connection to India was made through the LGBT magazine Bombay Dost and SHAKTI’s publications started getting circulated here. Before she left the management of SHAKTI to focus on the art scene, she helped found the Naz Foundation, which would become significant in the decriminalisation of Section 377.

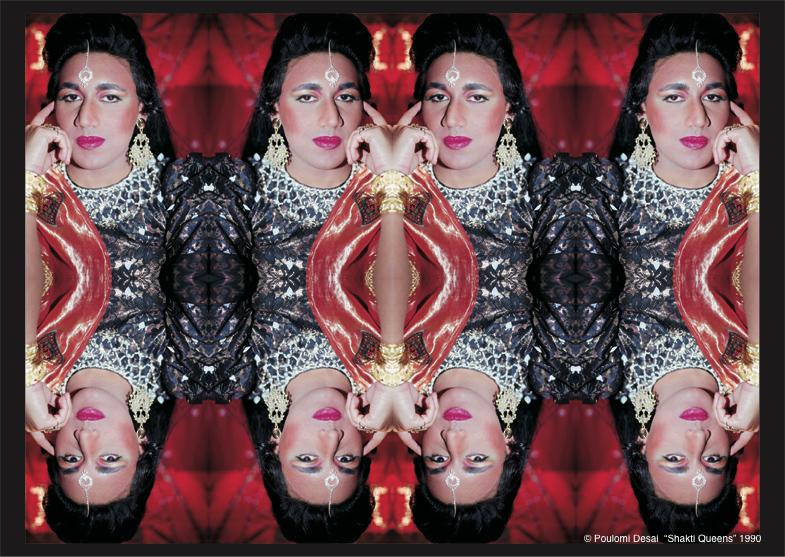

From the series Shakti (1990).

Desai’s practice moves beyond a linear trajectory to more of a response to sociopolitical issues happening around her. Operating beyond conventional gallery spaces, much of the work she did was to change the mass mindset on an everyday level. Community practices are significant to her work, like many artists such as Roshni Kempado— who founded Autograph the Association of Black Photographers—and also organisations like Cameraworks, who held workshops, teaching young people from marginalised communities about photography. “I view community practice from a political sense, like the way people perform together on the streets. That was our trajectory rather than as an individual artist trying to get into the Venice Biennale,” she said. After the Brixton Riots, money was poured into the area to stop riots and Desai joined the Lambeth Community Play, which culminated in a street theatre production and workshops. In 1993, Autograph commissioned her for a workshop where she worked with a group of women in Dhaka to become active participants in image-generation. Kempado writes in Shining Lights how the self-portraits which had been fragmented and painted upon, reflect a fluid notion of identity, which would remain across Desai’s work.

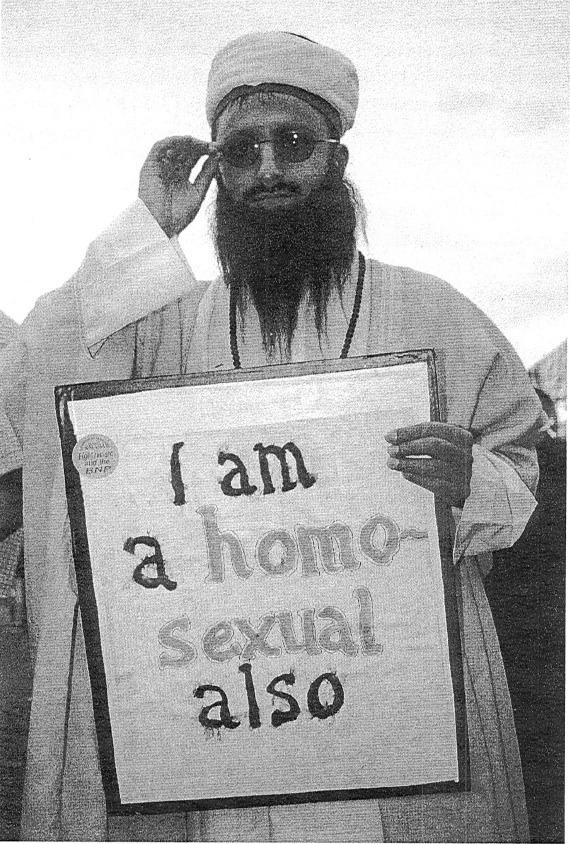

From the book Red Threads: The South Asian Queer Connection in Photographs (2003) by Poulomi Desai and Parminder Sekhon.

To learn more about South Asian diasporic artists navigating Britain’s racial and queer politics in the mid to late twentieth century, read Samira Bose’s reflections on Rasheed Araeen’s archive and Annalisa Mansukhani’s essay on Sunil Gupta’s retrospective show Come Out (2024). Also read Ankan Kazi’s piece on a panel discussion reflecting on the impact of print and digital cultures on photography as part of the conference Concerning Photography (2021).

All works by Poulomi Desai. Images courtesy of the artist.