My Father: Chronicles of a Dalit Textile Mill Worker in Mumbai

In the early twentieth century, Dalits of the Mahar caste began migrating to Mumbai, driven by the limited economic opportunities in rural areas and their marginal land holdings. Seeking employment in the burgeoning textile mills, this migration gradually diversified as Dalits pursued various non-textile roles by the 1970s. The representation of Dalits in the textile workforce declined from twelve per cent in 1940 to eight per cent by the late 1970s as many sought other fields. However, those unable to complete their education, such as my late father, Basvant Kamble, continued to find work primarily in the textile industry.

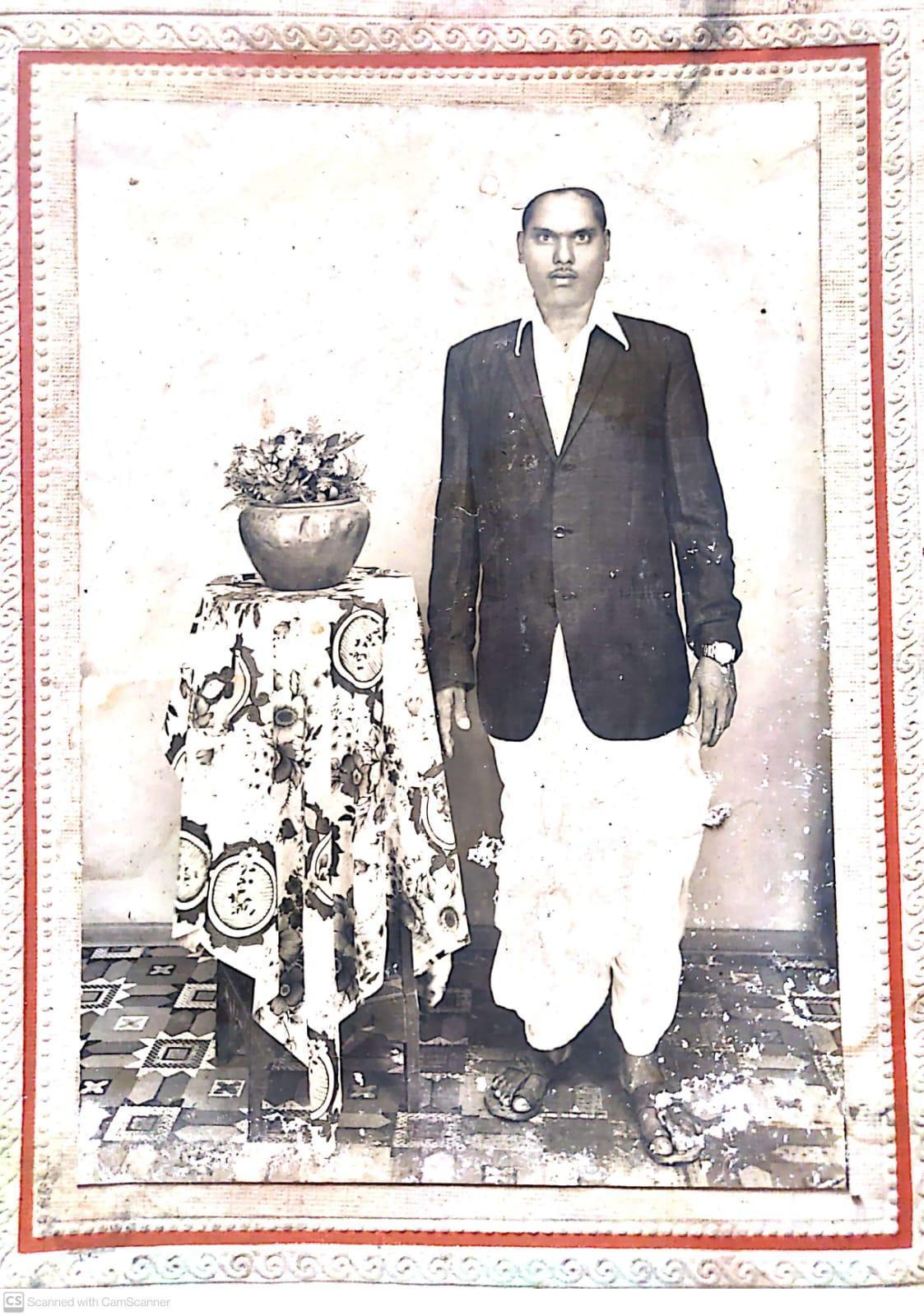

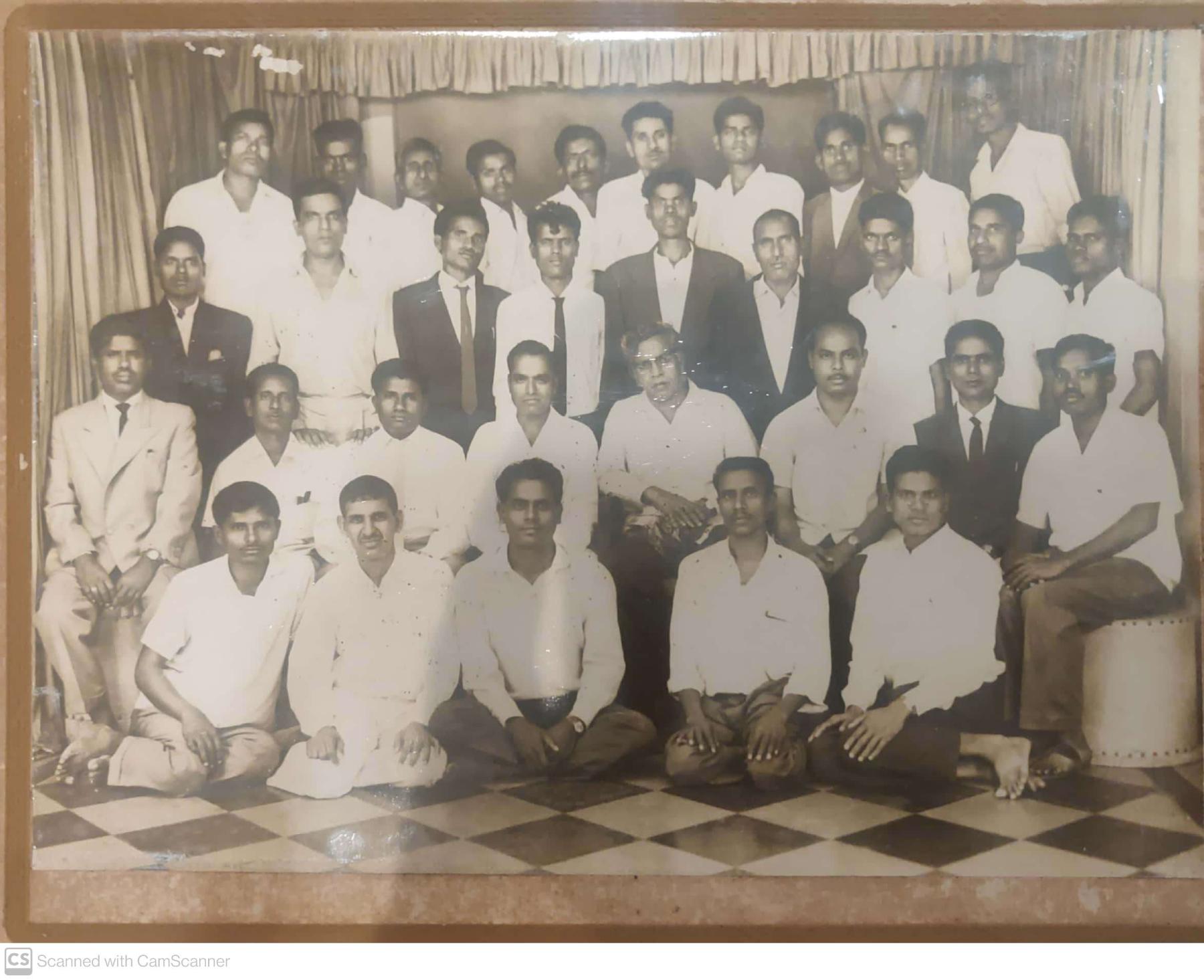

Basvant Kamble poses for a photo.

Kamble, born in a Dalit family on 18 November 1938, in Manwad near Kolhapur, grew up in this transitionary period. His father, Giryappa Kamble, who had some literacy in Marathi, had moved to Mumbai and settled in the B.D.D. Chawl on Delisle Road, a hub for textile workers. Following his father, Kamble’s elder brother joined the Khatav Mills, effectively freeing their family from traditional servitude to dominant caste landlords in Manwad. This migration also transformed Kamble's identity, shaped by the new socio-economic realities of the textile industry. Deeply influenced by Dr B.R. Ambedkar, he maintained a dignified appearance, adhering to Ambedkar’s message of self-respect and clean attire. Yet, he became a member of labour unions to protect his employment. I trace the journey of his transformation through receipts of his salaries and borrowings, membership cards to political organisations and photographs of his self-fashioning.

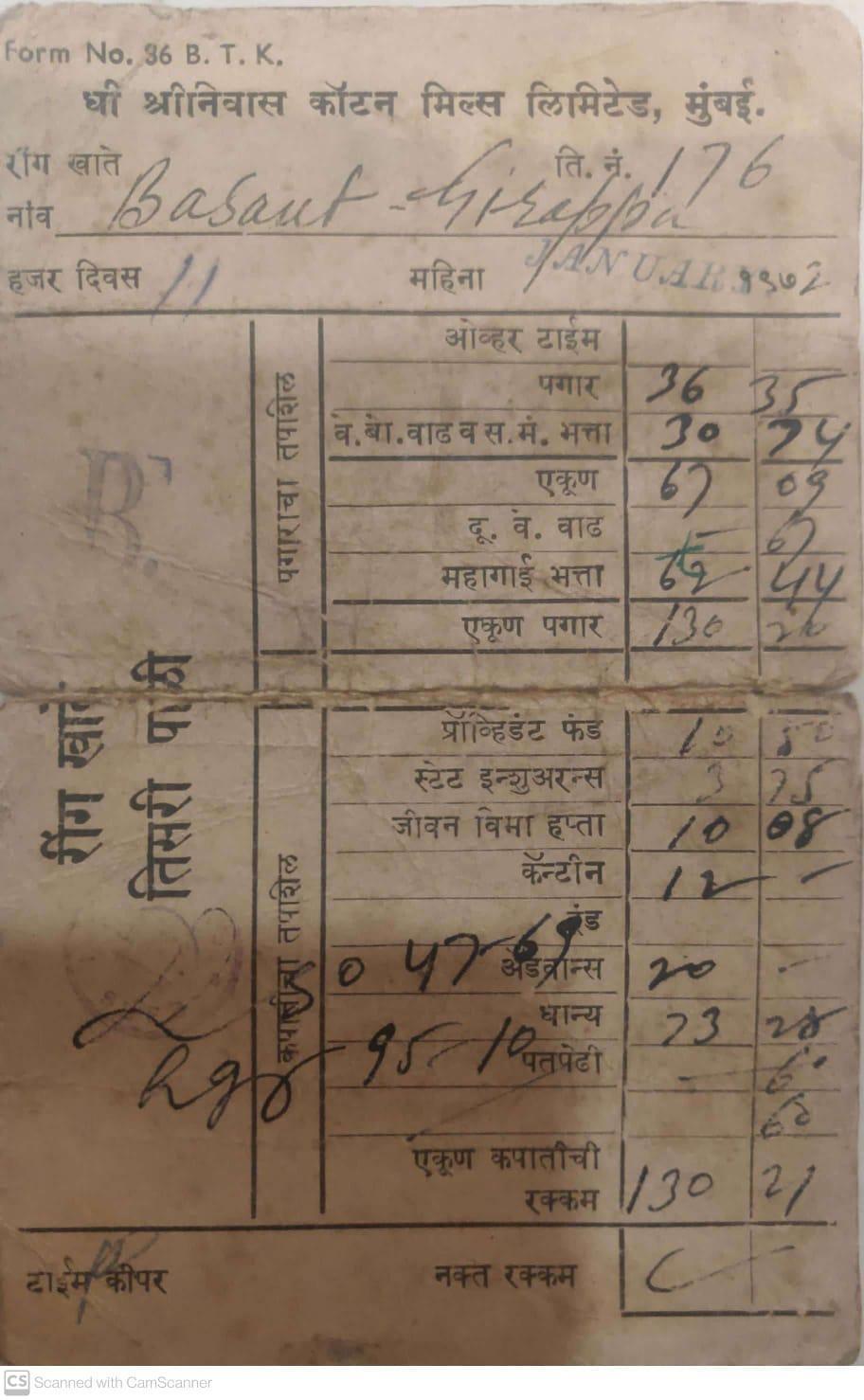

Basvant Kamble's salary slip from The Shrinivas Cotton Mills Limited, Mumbai. (January 1972)

In the 1970s, the Mumbai textile sector was in decline, paying meagre wages that barely supported the workers. For instance, in January 1972, Kamble’s pay was reduced to zero after deductions, despite working eleven days that month and initially earning Rs. 130. Numerous reductions were made for Provident Fund (Rs. 10), State Insurance (Rs. 10), Life Insurance (Rs. 10), Canteen charges (Rs. 12), Advance payments (Rs. 20) and Grain Shop expenses (Rs. 73). Similarly, in March 1977, despite working twenty-seven days and earning Rs. 618, after deductions totalling Rs. 578, he was left with only Rs. 40. This ongoing financial strain forced Kamble to rely on borrowing to manage daily expenses, resulting in growing indebtedness over time.

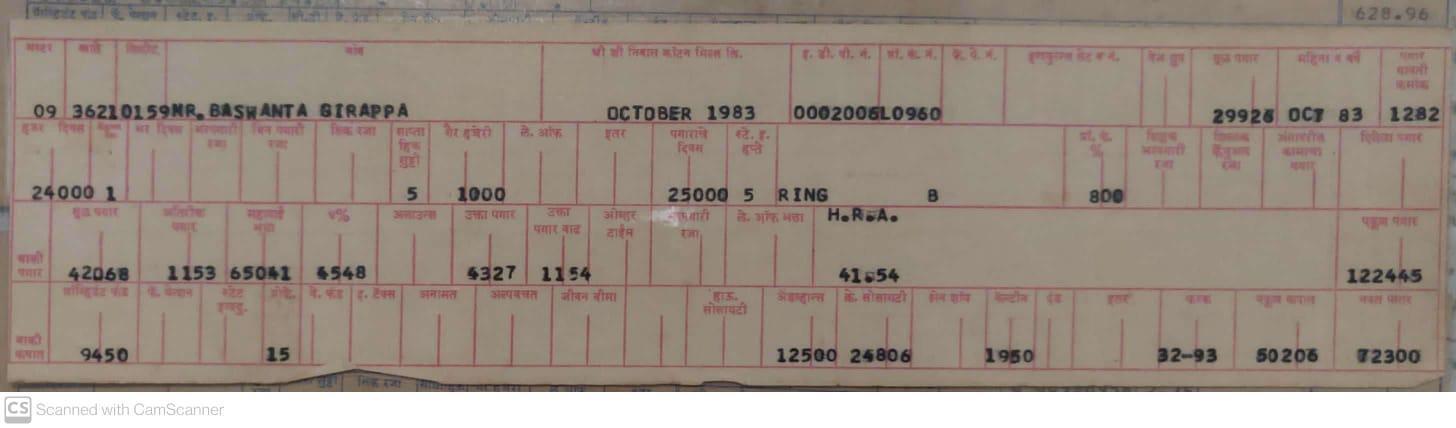

Basvant Kamble's salary slip from the Shrinivas Cotton Mills Limited, Mumbai. (October 1983)

The textile strike of 1982 significantly worsened conditions for Dalit workers, who already faced limited or no land ownership. When mills closed, they were left jobless, which led to their further marginalisation as they often lacked alternative employment opportunities and resources to fall back on. By October 1983, Kamble received Rs. 1,224 for his work; however, after deductions of Rs. 502, he took home Rs. 723.

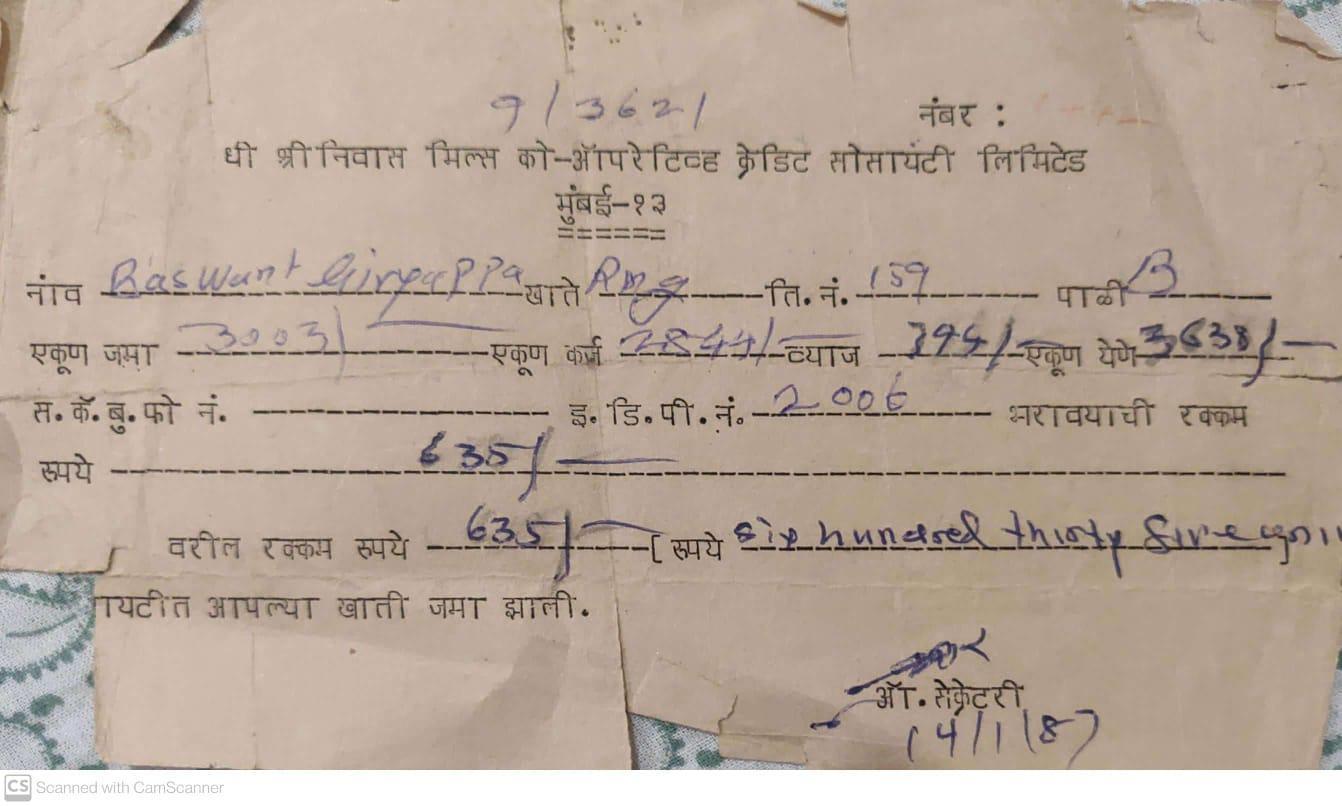

Basvant Kamble's personal loan document from the Shrinivas Mill Cooperative Credit Society Limited. (January 1987)

Amid the strike, when he joined the mill, he had to borrow Rs. 2,844 from the Shrinivas Mills Co-Operative Credit Society to meet his basic needs. The strike ultimately benefitted mill owners, who sold mill lands for commercial use, leaving the workers with unpaid dues and embroiled in a lengthy dispute between the builders Lodha and Hiranandani over property rights for the Shrinivas Mill.

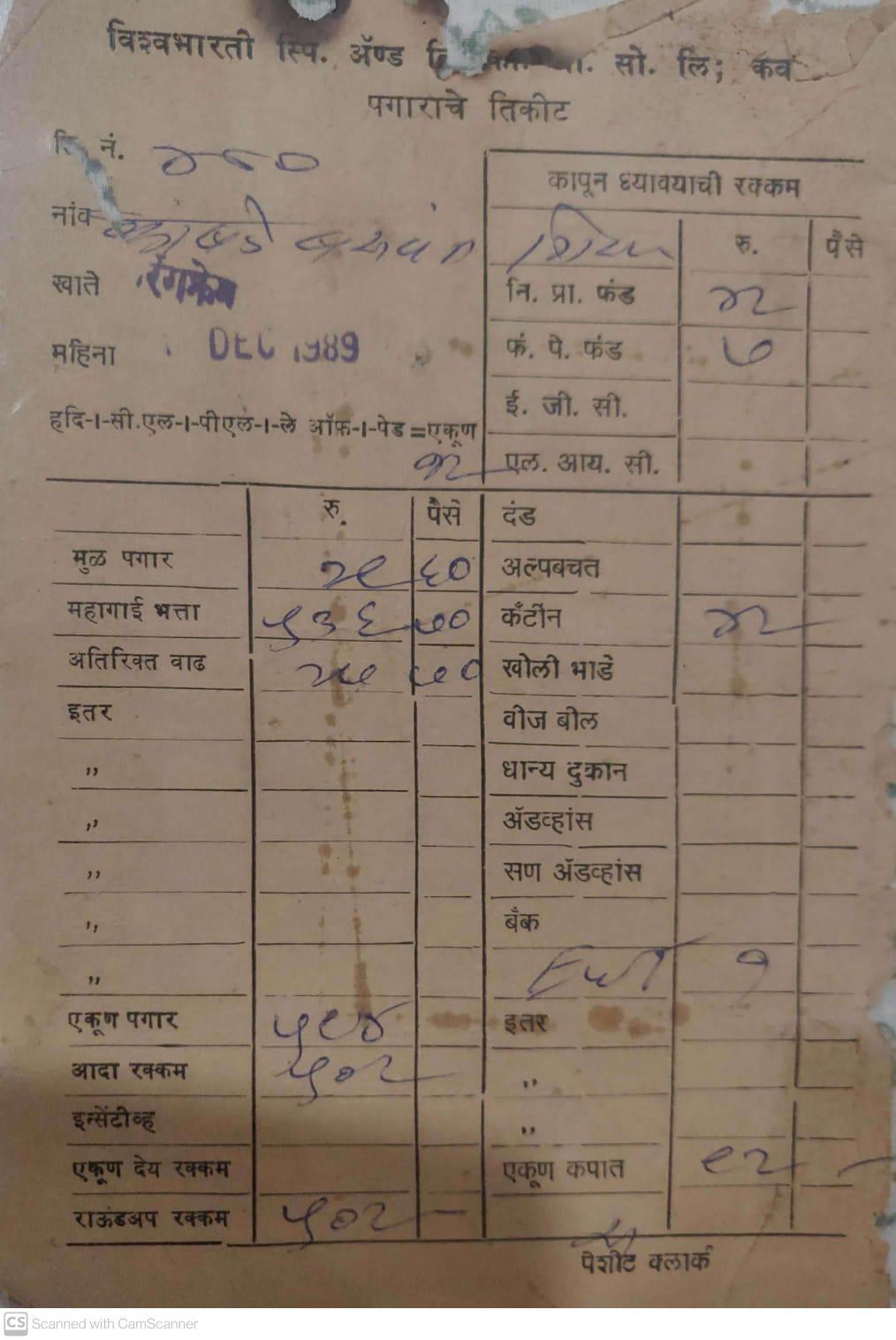

Basvant Kamble's salary slip from Vishwabharati Spinning and Weaving Cooperative Society, Kowad, Bhiwandi. (December 1989)

Following his job loss, Kamble relocated to Kowad near Bhiwandi and joined the Vishwabharati Spinning and Weaving Cooperative Society, which offered substantially lower wages than textile mills in Mumbai. By August 1990, he was earning Rs. 1,247, an amount he had last received in Mumbai’s Shrinivas Mill in 1983. The closure of this weaving mill in 1994 led him to return to Manwad, where he initially began his working life under oppressive caste hierarchies.

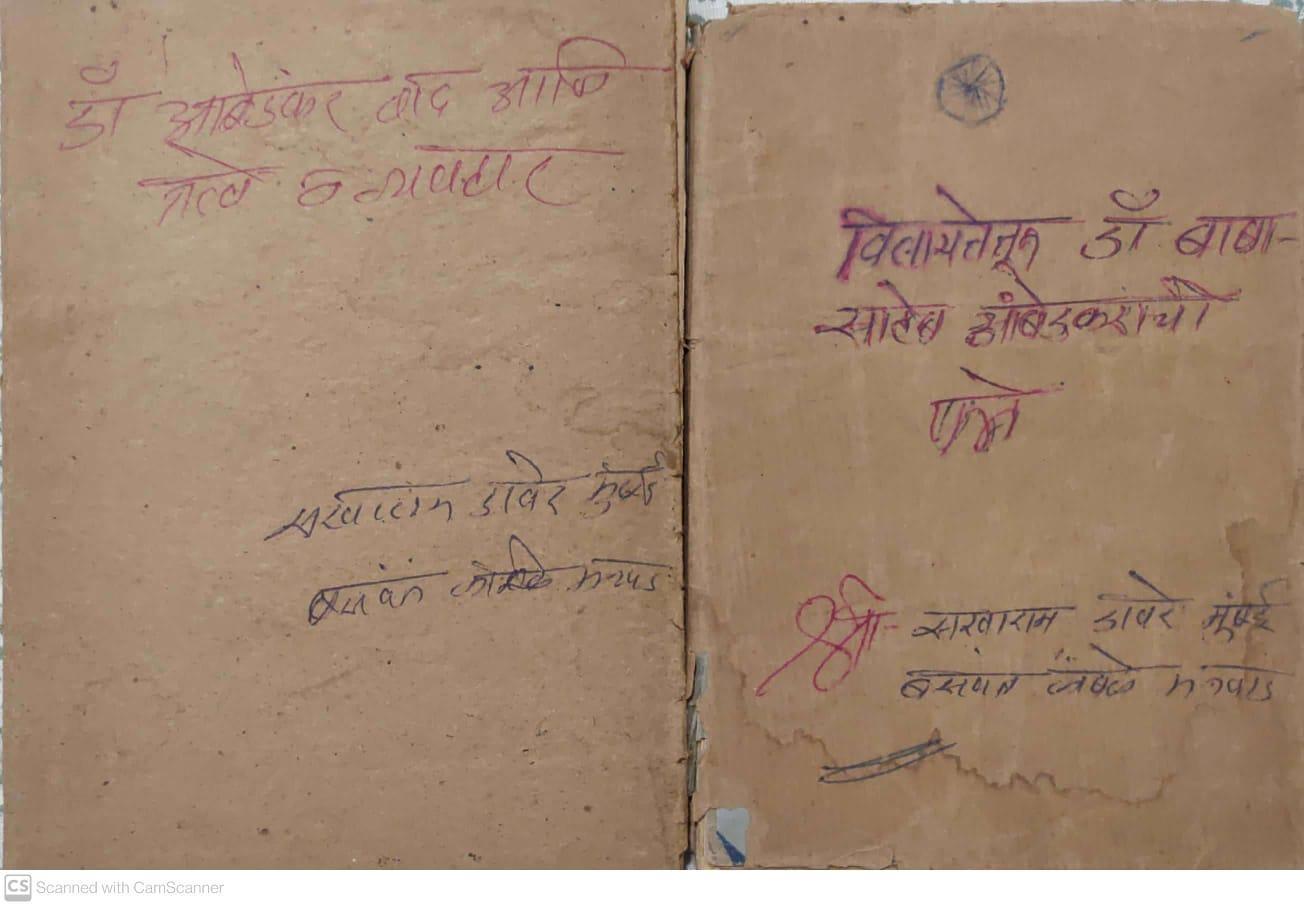

Books on Dr B R Ambedkar (Left: Dr Ambedkar Philosophy and Debate, Principal, and Practice, Right: Letters of Dr B.R Ambedkar from Foreign Land).

However, his time in Mumbai and exposure to the writings of Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar and the Dalit movement broadened his worldview and encouraged him to prioritise education for his children. By the 1990s, due to the Dalit movement's influence, reservation policies were implemented, enabling his two elder sons to secure positions in the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) and the Brihanmumbai Electrical Supply and Transport Undertaking (BEST) in the city, marking an improvement in their socio-economic circumstances. He maintained a friendship with Sakharam Davre, a former associate of Dr Ambedkar, who lent him various books, furthering Kamble's knowledge despite his limited formal education.

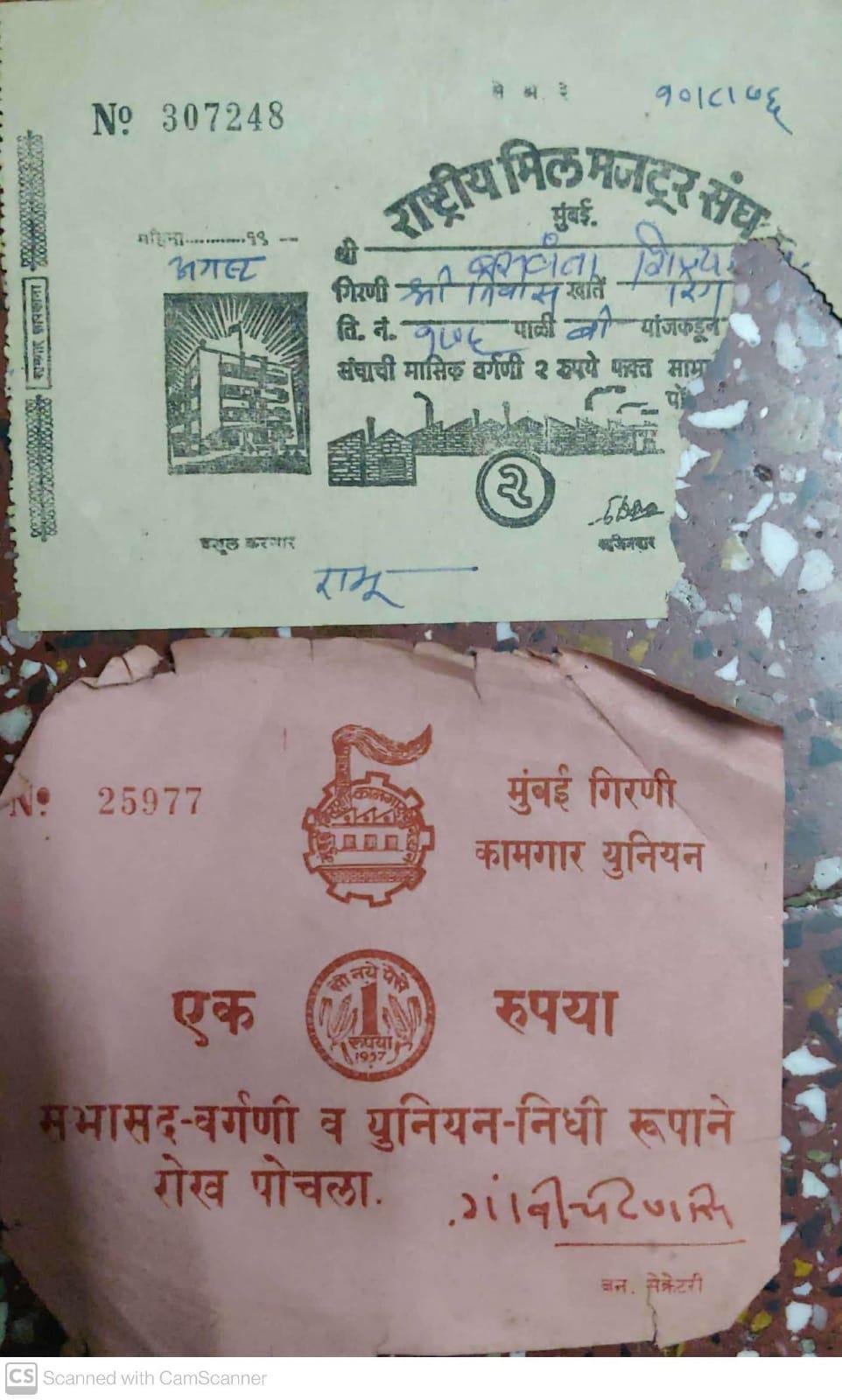

Receipt of Union Membership by Basvant Kamble, (Top- Rashtriya Mill Mazdoor Sangh, Bottom – Mumbai Girni Kamgar Union).

Navigating labour union politics, Kamble carefully balanced his associations, becoming a member of both the Rastriya Mill Mazdoor Sangh, a legal union, and the Mumbai Girni Kamgar Union, thus ensuring he remained politically neutral and safeguarded his employment interests.

Kamble’s passing in 2013 at the age of seventy-five marked the end of his journey—a life that encapsulated the struggles of Dalit workers from rural villages to urban mills and, ultimately, back to the village. His life story reflects a broader narrative of migration, labour and resilience among Dalit textile workers, highlighting their struggles against economic precarity and caste-based discrimination within industrial labour sectors. Kamble’s story is emblematic of a generation of Dalit workers who sought liberation from caste oppression through industrial employment, only to face new forms of economic and social challenges within urban industries.

Dalit Mill Workers posing for a photo ( Basvant Kamble- Extreme Left from Top Second Row) Image courtesy ofHitesh Kamble.)

To learn more about struggles against caste-based discrimination, read K. Sajaya’s ode to Professor G.N. Saibaba, Ankan Kazi’s essay on Dalit Camera, Sukanya Deb’s conversation with Vishal Kumaraswamy and Akash Sarraf’s review of Kathal - A Jackfruit Mystery (2023).

To learn more about the mill workers’ struggle in Ahmedabad, read Arushi Vats’ essay on Parthiv Shah’s documentation of the mills.

All images are from the Personal Collection of Babasaheb Basvant Kambale unless mentioned otherwise.