Reading Between the Signs: On Niharika Popli's If I Could Tell You

The title Sequence of the film.

Screening at the 9th edition of the Serendipity Arts Festival, If I Could Tell You (2024) is a non-fiction film by Niharika Popli about the lives of Surbhi and Charu, two working women from Delhi, who find themselves caught between the world of hearing and deafness. Charu, a deaf woman, grew up with a sister who was also deaf but a family that was not. Surbhi, a hearing person born to deaf parents, grew up with Indian Sign Language (ISL) as her mother tongue. Their experiences come together as intimate conversations about deafness, language, independence, body, dreams, family and society. The film centres these themes within their shared experience of being women.

Hardeep, a poet and artist, performs poetry in ISL.

The film gently guides us into the world of deafness through an introductory sequence of a poem performed in ISL by Hardeep, an artist and ISL poet. The poetry is first recited in ISL and then translated for viewers to understand. In doing so, the film allows for poetry to extend beyond words and for words to extend beyond a conventional notion of what language is. There seems to be a universality to certain gestures—like the heart beating, a bird flying or the act of breathing—that make sense to us even before the ISL is translated. This sequence sets the tone for the conversations that unfold through the film.

Charu is introduced to us while she meanders through traffic in her car. The limited visibility of disability rarely conjures up the image of a disabled woman driving herself around the city. We learn from her that she was introduced to ISL only when she was seventeen-years-old and up until that point she and her sister communicated through their own made-up signs.

Charu drives around Delhi.

For Charu, learning ISL was an entry ticket into the world that existed beyond the confines of her home, that she had been dying to be a part of. We see her in action, running a forum called “Deaf Women Too”, where she works to create a tightly knit community of independent and empowered deaf women. The visual of Charu in the driver's seat can be read as symbolising how she is driving the change she wishes to see in the world and pushing the boundaries that society has desperately tried to impose upon her.

Surbhi, having grown up with deaf parents, learnt only much later when she went to school that everybody did not sign at home. She begins to see her own lived experience as being different: “It was as if I was part of two very different worlds, the deaf world and the hearing world.” She opens up about the challenges that come with being a CODA (Child of Deaf Adults) and how her parents' dependence limited her experience of independence.

(Left) Surbhi with her parents. (Right) Charu with her family.

The contrasting experiences of Charu and Surbhi come through in their discussions about family. While Surbhi, as a CODA, was constantly relied upon by her parents, Charu had the opposite experience, with her parents viewing her more as a dependent. We see how having language allowed Surbhi to communicate with her parents and for them to communicate back to her. With Charu’s parents and brother having limited fluency in ISL, both she and her sister always found themselves struggling to keep up with conversations at home, grasping only half the story on most occasions. She shares how “...not having language as a kid really messes with the development of your brain. It is like you are missing a part of yourself, your identity, and there is this whole sense of community that you are left out of.”

Sreelekshmi, a Mohiniattam dancer, moves without music.

The film extends the idea of deafness by drawing connections to dance, gestures, make-up, poetry, art, theatre, acting, movement and expression. We see Sreelekshmi, a Mohiniattam dancer, dancing and moving, not on stage but in the middle of a road. There is no music, only the faint ambient sounds of a city waking up. Sreelekshmi also shares how she was always pulled up as a child for not talking. Dance and movement helped her to express that which she could not express in words.

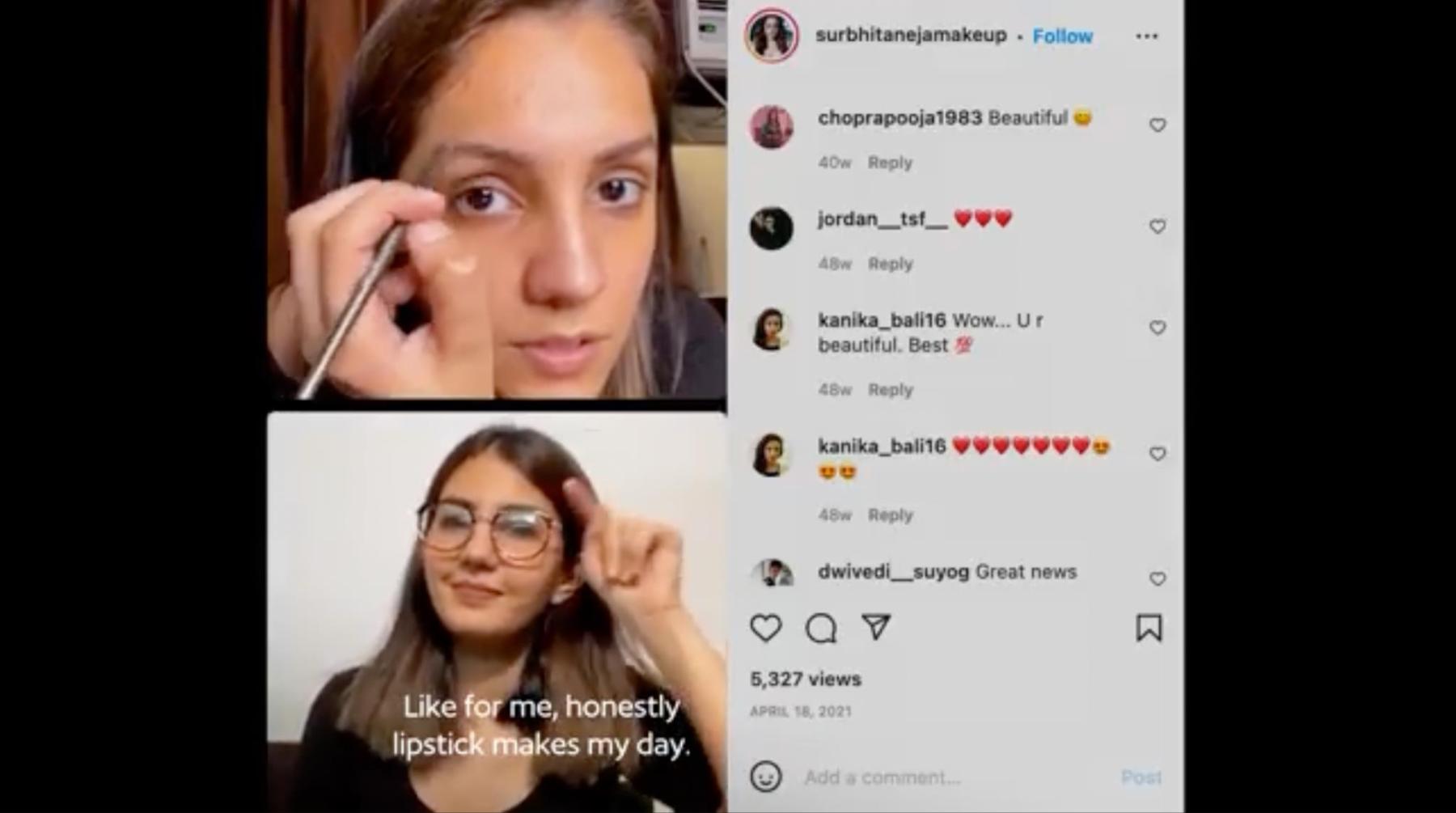

Surbhi’s Instagram make-up tutorials with her sister.

Surbhi's work as an interpreter in the advocacy space weighs on her given the intensity of cases she often has to encounter. She uses make-up as an escape from all that she finds heavy in life and as a means to be joyful. Surbhi and her sister’s dream to open a make-up salon segues into the world of drag, with make-up becoming a tool to escape the harsh realities of the world. We are introduced to Ayushman, known as Lush Monsoon, who speaks about how make-up gives them the confidence to reveal parts of themself that they would be reluctant to express as Ayushman.

Ayushman aka Lush Monsoon.

Through a visual sequence of play in gestures, we are introduced to Lauren, an actor and drama teacher. They share how theatre allowed them to use their body to express emotions that they was not able to verbally articulate. They find that “in movement there was such an honest and authentic depiction of my feeling.”

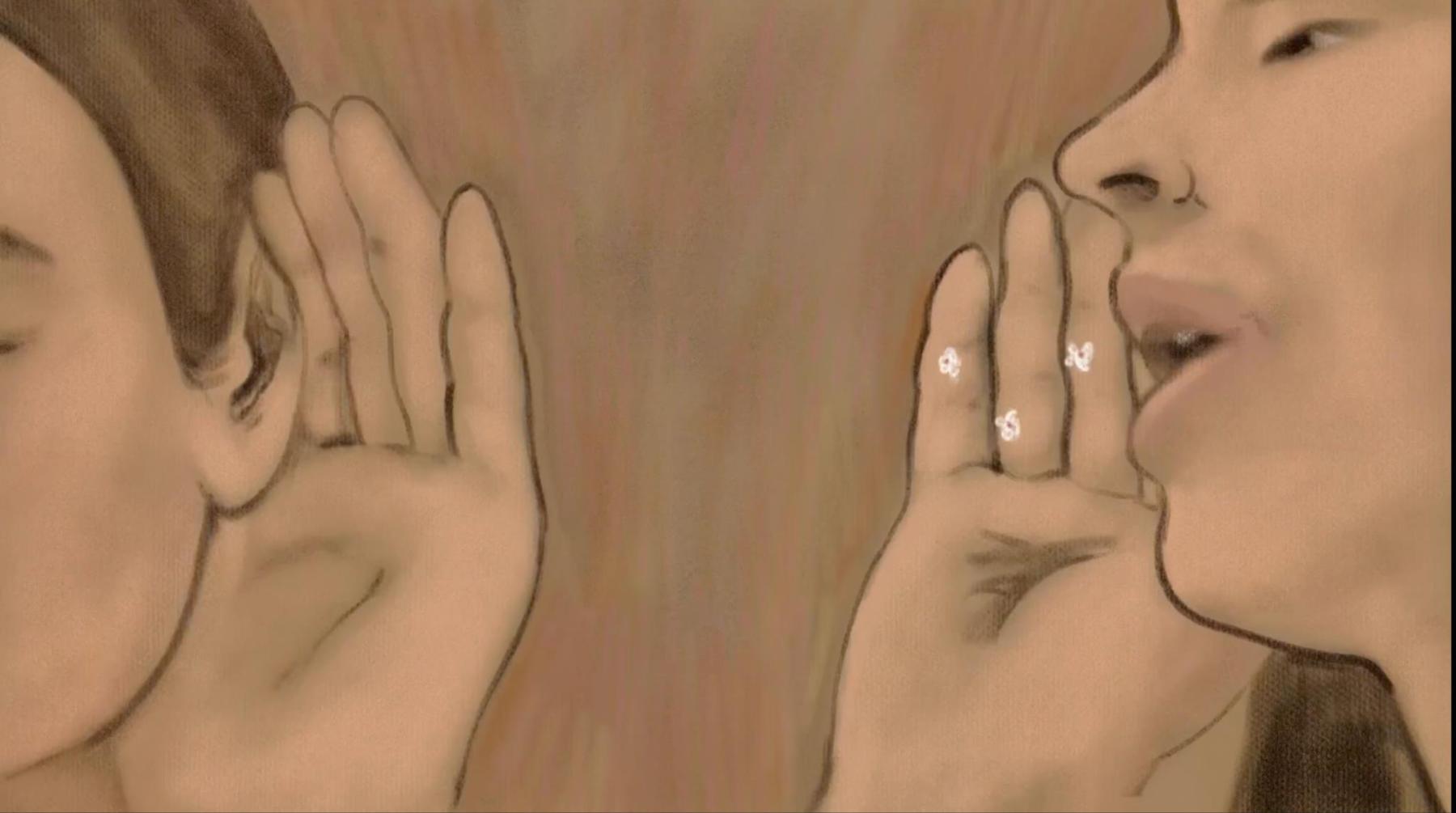

If I Could Tell You also interestingly weaves together multiple visual styles and elements. The film is punctuated by animated sequences created by Pakhi Sen that visualise the unspoken and the unsaid. Stylistically constructed sequences are broken by visual montages of Zoom calls and meetings, screengrabs from social media and Instagram handles, as well as photographs from family archives.

Awareness session on dowry by Deaf Women Too.

The film deviates from the conventional interview editing styles that employ visual cutaways to represent what is being spoken. With Charu and Surbhi and many of the other characters in the film signing, the choice to stay with them seems to be a conscious one made by the filmmaker to force the audience to listen and be completely present. There is a whole section in the film where Charu observes the boredom that the cinematographer seems to be experiencing as a result of not following the conversation. She extends solidarity to him by sharing how she is often stuck in a similar position around her family when they converse without signing. This candid, almost behind-the-scenes moment,which was thankfully not discarded by the filmmaker on the edit, seems to capture so much of what the film is trying to relate to the viewer.

Still from If I could Tell you of Charu(R) and Surbhi(L)

Through the experiences of these many women, the film makes us familiar with the world of the deaf. By the end of the film, we realise we can listen without hearing and speak without talking, allowing for us to not only redefine our idea of deafness but also relook at our own conditioned ways of speaking and listening. We begin to see how the experience of the world is not limited by deafness; it is the experience of deafness that is limited by the world.

Animation sequences by Pakhi Sen.

To learn more about artists responding to the representation of differently abled persons, read Arti Das’ essay on Salil Chaturvedi’s Places My Chair Likes to Go (2022) exhibited at the Serendipity Arts Festival 2022 and Arushi Vats’ essay on Shweta Ghosh’s We Make Film (2021).

To learn more about this year’s edition of the Serendipity Arts Festival, watch the walkthrough of the exhibition Carbon (2024) with Ravi Agarwal and David Verghese, an interview with Dayananda Nagaraju and Niranjan NB as they speak about their project The Everlasting River (2024) and Aparna Chivukula’s essay on Ghosts in Machines (2024) curated by Damian Christinger.

All images are stills from If I Could Tell You (2024) by Niharika Popli. Images courtesy of the artist.