Archives of Agrarian Unrest: The Sivalokathyagar Temple

Since the ninth century CE, and over the course of their 400-year rule, the Cholas filled the deltaic region of the river Kaveri with a highly concentrated network of stone temples with intricate sculptures. A typical South Indian temple is seen as a remnant of a bygone era of cultural and technological supremacy. However, they have also played a significant role in defining social roles based on caste and acted as spaces for political contestations with agrarian communities in South Indian society.

The Brihadeeswara temple, located in Thanjavur, is the tallest structure constructed in the year 1000 CE by Rajaraja Chola I. In popular imagination, the temple is constantly used as a symbol to evoke cultural pride. (Image by author)

The granite stones that make up the temple structures act as archives of agrarian unrest. Etched on with records of donations made to temples (in forms of cattle, men, women, land and metal), they document details about land transfers, measuring rods, floods and droughts, human sacrifices and, most interestingly, unrest and rebellions.

An eleventh-century inscription that documents agrarian resistance inscribed on the walls of Sivalokathyagar temple at Achalpuram village. (Image Courtesy of Gopinath Sricandane)

One such record is inscribed on the stone walls of the Sivalokathyagar temple at Achalpuram, a village in the Kaveri delta. The event in question was an instance of unrest in 1177 CE under the reign of Rajadhiraja Chola II. The inscription records the resolution that the village administrative body arrived at in order to address the concerns of tenants of the village. Though a majority of such inscriptions are published by the Archaeological Survey of India and are publicly accessible, visiting the temple and the village where the inscription is inscribed forms an important part of the research process. The act of seeing and documenting during field visits provides an understanding of the landscape, its ecology, and the continuing impact of these forgotten histories on the people who inhabit this land.

Even though temple inscriptions can act as public records and primary sources of history, until recently, entry to temples was only accessible to upper castes. Here, a child visiting Achalpuram temple develops curiosity about the inscriptions after witnessing our team’s attempts to read them. (Image Courtesy of Gopinath Sricandane)

Achalpuram is one of many villages that were known as Brahmadeyas. Along with agricultural land, these villages were donated to Brahmins by turning the existing owners into cultivating tenants (ulukuti / உழுகுடி). On the one hand, tenants now had to pay a share of 60 percent of the total produce from the land as tax. On the other, Brahmins received concessions on the tax they paid to the king, such that these lands began to be called tax-free lands (iraiyili / இறையிலி).

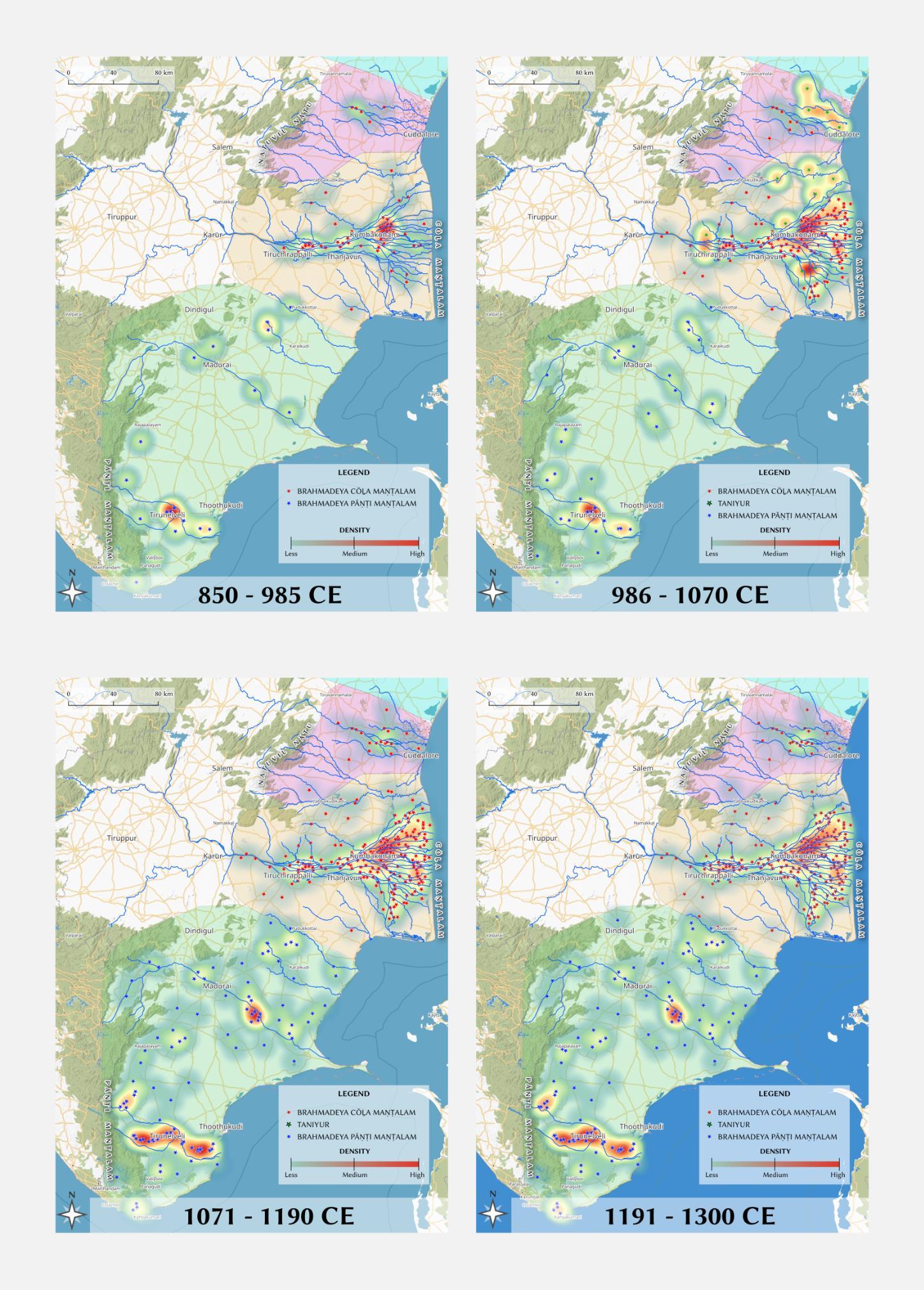

Map showing the increase in number of Brahmadeya villages (villages that were donated to Brahmins) between 850 and 1300 CE in four stages. (Map created by Ganesh Gopal)

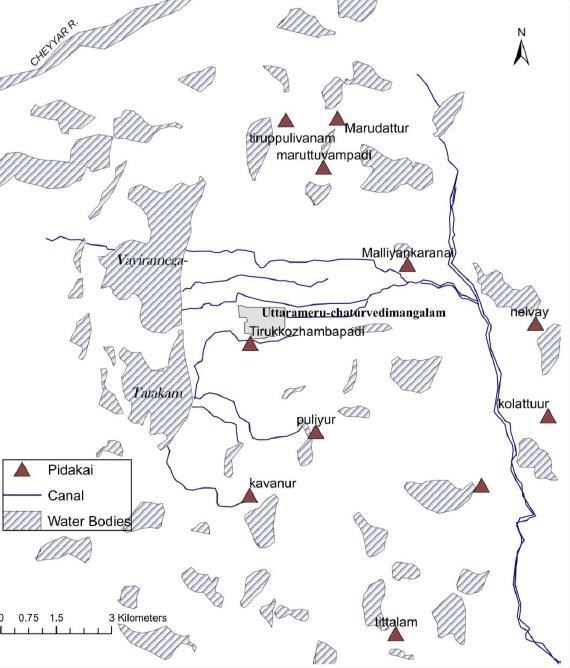

Brahmins did not engage in any physical activity that related to cultivation, owing to the graded hierarchy in work and their ritual purity. In fact, one of the clauses in the Achalpuram inscription even says that Brahmins should not be involved in cultivation. Spatial segregation among castes was also clear, with the Brahmins living at what was called Ur (ஊர்) surrounding the temple, while the tenants and servicing castes lived in satellite settlements around the Ur called Pidakai.

Map of Uttaramerur Village, which used to be a Brahmadeya. At the centre is the Brahmin settlement or Ur. Settlements of tenant cultivators or Pidakai are far away from the main village and are tucked between lakes and paddy fields. (Map created by Y. Subbarayalu)

The Achalpuram inscription begins by saying that the following is to the attention of tenant cultivators who live in separate quarters (pidakai / பிடாகை) around the main Brahmin settlements. Tenant cultivators were agrarian communities that were called Vellalas. As per the inscription, there seems to have been an increase in the rent, which the cultivators resisted. While the inscription only records the final resolution and not the process of negotiation, some inscriptions in surrounding areas even go on to record that the tenant cultivators migrated out of the village in protest of increased rent and forcible collection methods.

Large granaries in Srirangam temple stored paddy that tenant cultivators paid to the temple as rent for cultivating in the temple land. Temples, even today, remain the largest landowners in the whole of Tamil Nadu. (Image by author)

The Achalpuram inscription goes on to record the new decreased rent as a result of the protests and thus acts as evidence of peasant resistance in the region. Rent on wet irrigated lands was higher in comparison to dry rain-fed lands, as the former was more fertile and amenable to paddy cultivation. Paddy played a central role in the medieval Chola economy, as it also acted as currency, hence the higher value. Taxes and wages were often paid in the form of paddy. These agrarian relations that were established by the Cholas continue to exist in the present, having survived the several regimes that followed.

Women agricultural labourers transplant paddy as the landowner, clad in white veshti and shirt, walks on the bund. (Image by author)

Achalpuram stands out as a rare case in the history of Chola temple architecture where moments of resistance by tenant cultivators—who had little to no control over the Brahmin temples—have found a place on the temple walls. While temple inscriptions discuss the lives and roles of the intermediary castes such the Vellalas, agrarian tenants and servicing castes remain undocumented. Moreover, the inscription fails to give us detailed information about the lives of landless labourers and formerly enslaved people whom medieval society deemed as “untouchable”. As seen above, it could be fairly argued that cultivation was possible mainly because of the hard work and toil that these labouring classes rendered for minimal or no pay. Hence, temple records become crucial evidence in understanding peasant unrest in precolonial South Indian society, as well as continuing agrarian relations today.

To learn more about revolutionary agrarian imaginations, revisit Kamayani Sharma’s essay on Gurvinder Singh’s Trolley Times (2023), Anisha Baid’s conversation with Savitri Sawhney on Pandurang Khankhoje, Ankan Kazi’s essays on Munem Wasif’s Seeds Shall Set Us Free II (2019) and Jahnavi Phalkey and Laurie Sumiye’s The Gold of a Yellow Plant (2021) as well as Annalisa Mansukhani’s reflections on Dharmendra Prasad’s practice.