The Tokyo Trial: “Victor’s Justice”?

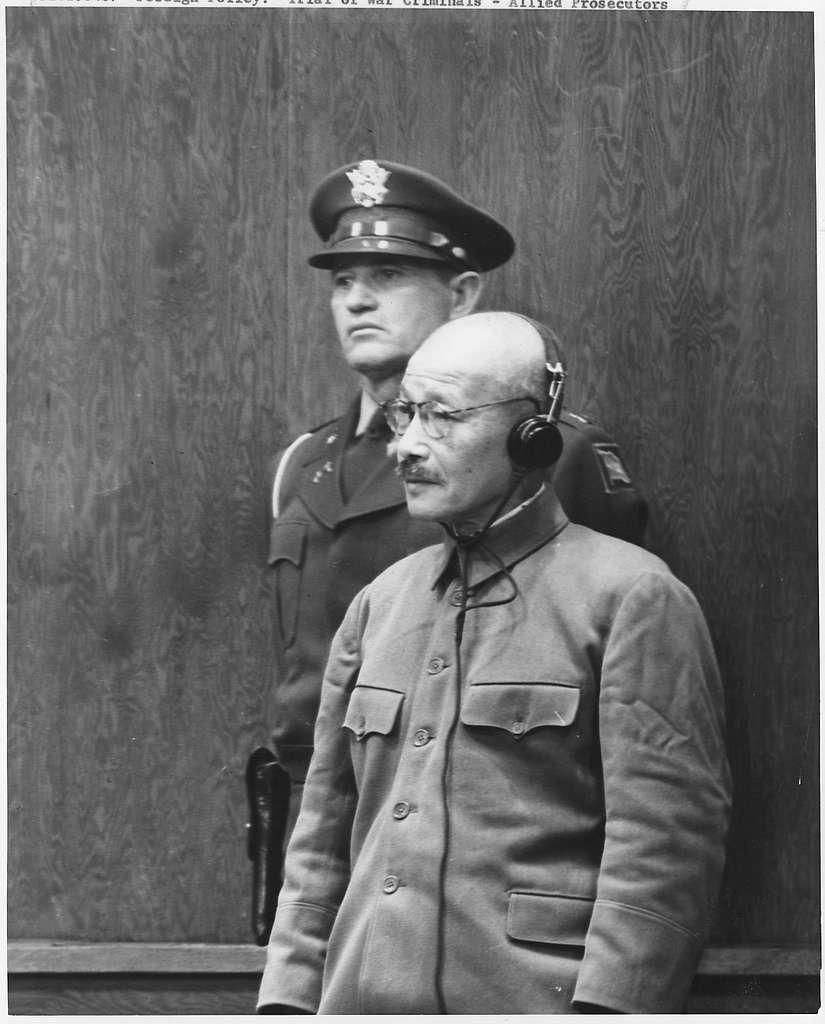

Tojo, Former General, Premier and War Minister for Japan between December 1941 and July 1944, was amongst the accused sentenced to death by hanging by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East. (Image courtesy of PICRYL.)

In the first part of this essay, we saw how W.E.B. Du Bois’ concept of “the colour line” can explain why atrocities that were being committed by the West onto the colonial peoples went without consequence, but provoked a stringent response when committed in Europe during WWII. Thus, the Nuremberg Trials, held by the Allies against representatives of Nazi Germany, laid the foundations of international criminal law. Soon after, and taking Nuremberg as its precedent, the International Military Tribunal of the Far East—also known as the Tokyo Trial—persecuted twenty-eight Japanese officials for crimes committed in the period between the 1928 Pact of Paris and the end of WWII in 1945.

Promotional poster of the docu-drama Tokyo Trial.

The riveting four-episode docudrama Tokyo Trial (2017) demonstrates how these trials were intended to discuss the “right step for humanity to take” by universalising law as founded in Nuremberg. Repetition of the Nuremberg verdict was thus imperative. In the second episode, the New Zealand representative, Sir Erima Northcroft, says: “If the Tokyo tribunal does not strictly adhere to Nuremberg principles, it would mean passing judgement on the Nazis was a mistake. We cannot let that happen.”

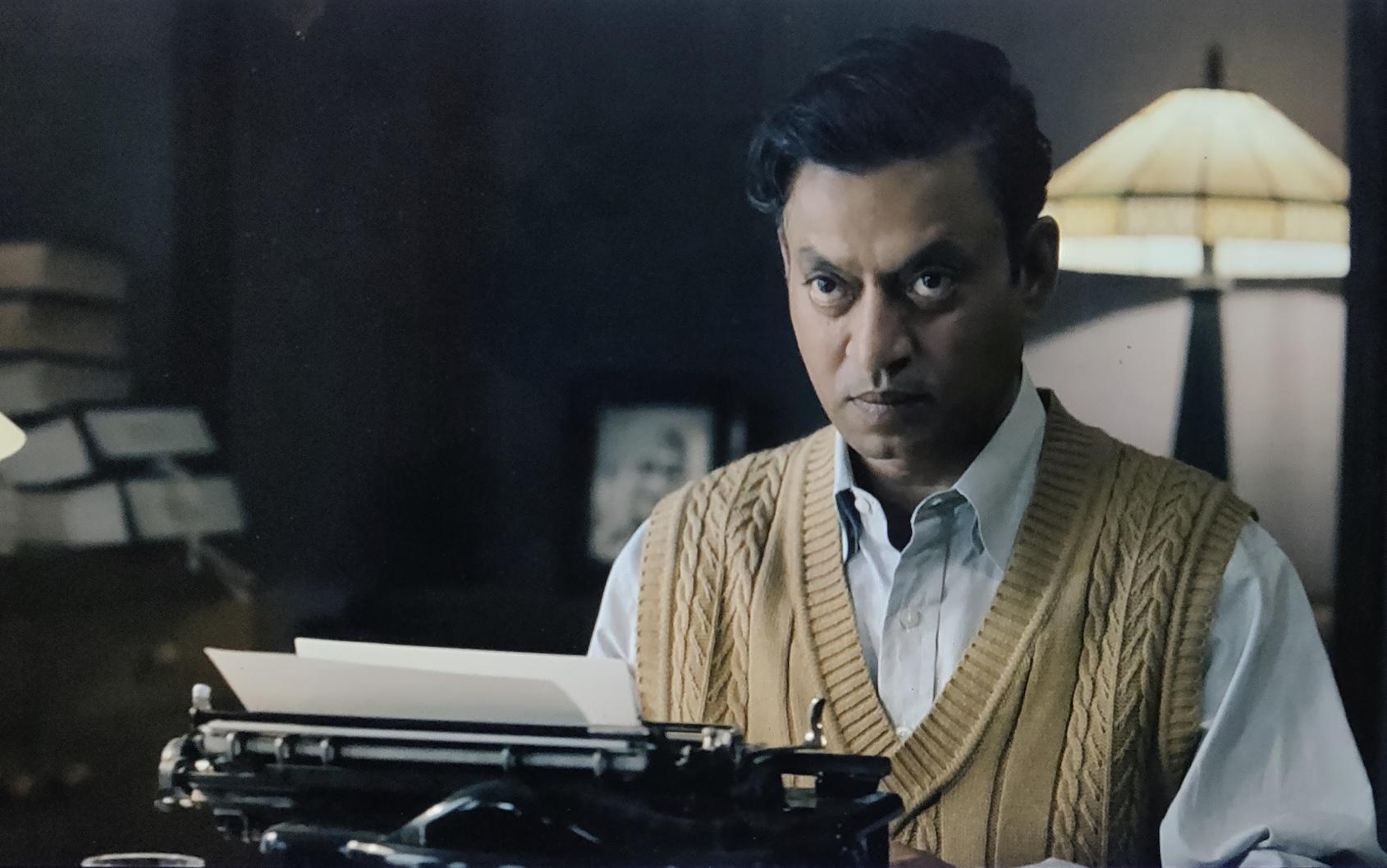

Justice Radhabinod Pal gave a dissenting verdict in the Tokyo Trial.

This statement comes soon after the Indian appointee to the tribunal, Justice Radhabinod Pal—played by the late Irrfan Khan—motioned for the acquittal of all defendants on all counts. Arguing against retroactive criminalisation, Pal questions the validity of the charge of crimes of aggression. While he condemns Japan’s actions across Asia as “devilish and horrid,” Pal contends that the Japanese officials who committed these atrocities were tried in local courts and given sentences. Thus, while the 1928 Pact of Paris—to which Japan was a signatory—condemned war, “it does not provide legal ground for criminalising war… and it certainly doesn’t say anything about individual perpetrators.” In other words, it was not until Nuremberg that war was considered a crime. Under these circumstances, convicting the defendants, Pal contended, would be seen as “revenge,” or victor’s justice.

Japanese defense counsel Mr Kiyose challenges the authority of the tribunal.

The fact that the Pact of Paris did not consider war to be a crime was precisely the basis for defence counsel Mr Ichiro Kiyose’s challenge to the authority of the tribunal to try crimes against peace, as shown in the first episode. The captivating courtroom scene follows another defence counsel, Mr Ben Bruce Blakeney, who argues,

“Killing in war is not murder follows from the fact that war is legal. This legalised killing, justifiable homicide… however repulsive, however abhorrent, has never been thought of as imposing criminal responsibility. If the killing of Admiral Kid by the bombing of Pearl Harbour is murder, we know the name of the very man whose hands loosed the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. We know the chief of staff who planned that act, we know the chief of the responsible state.”

Reporters ask the Tribunal President if he will press charges against U.S. President Truman for bombing Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

As if to make clear the implication of the defence statement, this scene is followed by a reporter asking the tribunal’s president, William Webb, “Are you going to press charges against President Truman for the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki?” Herein returns “the colour line.”

Justice Röling and General Zaryanov discuss Napoleon.

The Tokyo Trial was beginning to reveal the double standards of the West; the encounter between Justice Bert Röling from the Netherlands and Major General Ivan Michyevich Zaryanov from the Soviet Union in the third episode is instructive. When asked why he was reading about Napoleon, Röling says that although Napoleon waged aggressive war, since there was no law against it, he was not executed but exiled to Elba. General Zaryanov retorts, “It is more likely that the kings and emperors of Europe saved him because they didn’t want to see themselves beheaded every time they lost a war.”

Justice Pal prepares his 250,000-word dissenting judgment.

Soon after the meeting with the General, Röling is shown with Justice Pal, who argues that it was only after the end of the Edo period in 1868 that Japan moved from being an isolationist to imitating Western nations, “most of whom were expanding and colonising for economic profit,” putting them “at odds with those they were imitating.” Justice Pal’s arguments against the persecution of the defendants echoes Du Bois’ explanation for Japanese resistance against the accumulation of new wealth on an unprecedented scale in Europe which comes from “Asia and Africa, South and Central America, the West Indies and the islands of the South Seas.”

In “The African Roots of War” (1915), Du Bois delineates the role of Japan in disrupting European imperialism, worth quoting in length:

“Japan has apparently escaped the cordon of this color bar. This is disconcerting and dangerous to white hegemony. If, of course, Japan would join heart and soul with the whites against the rest of the yellows, browns, and blacks, well and good…But…there are signs that Japan does not dream of a world governed mainly by white men. This is the ‘Yellow Peril,’ and it may be necessary, as the German Emperor and many white Americans think, to start a world-crusade against this presumptuous nation which demands ‘white treatment.’”

Justice Pal and Röling discuss colonialism.

Pal’s views that Japanese actions during WWII must be viewed within the context of European colonisation and exploitation of the Asian-Pacific peoples are further clarified in an endearing scene between Pal and Röling in the second episode. Pal says:

“Here in Tokyo we are talking about justice in the modern world. And yet a large part of Asia is still colonised by the West… So what gives the Dutch, the English, the French, or the Americans, the right to judge the Japanese for their claim that they wanted to free Asia?”

Further, Pal asks Röling to consider Dutch suppression of Indonesians in the “so-called Dutch East Indies,” including the sending of 100,000 soldiers. However, Röling’s defensive response that “we have tried to bring them prosperity… With all the chaos, we had no choice… Do you ever stop banging the same drum (of colonialism)?” makes Pal chuckle and sarcastically remark, “Your colonialist spirit is alive and well… We bang drums while you send troops to fight so-called terrorists. In reality, they are freedom fighters who want to reclaim their country.”

China's Justice Mei insists that the Tribunal must concern itself with the actions of the Japanese, not the Americans.

Although historic, Pal’s dissent was unable to prevent the persecution of the twenty-eight Japanese officials owing to the Tribunal’s majority judgement. The tribunal’s verdict was meant to further the law towards greater justice, but it would be fifty years before the International Criminal Court (ICC) would be set up in 1998. Significantly, America and Israel are still not members of the ICC since, they claim, it compromises their national sovereignty. Justice Mei, from China, dismissed Mr Blakeney’s arguments against America on the grounds that “We’ve been appointed to judge Japanese war criminals, not the actions of the Americans. That may be for a future tribunal.” Yet nearly eighty years later, that future still awaits, even as the West’s civilising mission continues unabated.

What is the valence of Justice Pal’s position today, then, particularly in the context of South Africa’s genocide case against Israel at the International Court of Justice (ICJ)? Was the Tokyo Tribunal’s concern for future world peace reserved for Europe, setting a precedent for the impunity of crimes committed by the West in Asia, Africa and the Middle East? Does the ICC protect universal human rights, or does it demonstrate the continued existence of Du Bois’ colour line? I will explore these questions in the third part of this essay.

In case you missed the first part of the essay, read it here.

To learn more about contemporary practices that interrogate the multivalent histories, watch a two-part conversation with filmmaker Mariam Ghani on the Afghan Film Archives, Mallika Visvanathan’s essay on the practice of Amar Kanwar and Ankan Kazi’s report of a panel discussion exploring communal and partition violence in Eastern India.

All images are stills from Tokyo Trial (2017) unless mentioned otherwise.