A Fragmented History: Contemporary Filmmaking in Assam

Contemporary cinema from the Northeast reflects the ‘homegrown’ nature of the industry, helmed by the proliferation of digital and new medias, alternative sources of production and sustenance. (Left:) Poster for Khawnglung Run. (Right:) Poster for Crossing Bridges (Source: IMDb).

The cinemas from the Northeast region of India can be said to have had a fragmentary history. In the 1930s, Assamese cinema, however intermittent, pioneered the region’s filmic journey, witnessing a revival in the contemporary moment. Manipur too has a significant cinema culture, and while it has seen many changes owing to the socio-political situation, it ultimately succeeded in devising a working model of its own. The penetration of digital technologies has meant that the rest of the textured region has also made its presence felt in terms of both cinematic ventures as well as the discovery of alternate modernities with the proliferation of new media. Inheriting the characteristics of the region’s rich and complex history, this digital media culture is configured with an inherent local feature stamped on it. Crises mushroom multiple meanings, and in the case of northeast ‘regional’ cinema history, it produces a distinctive cinema of the homegrown.

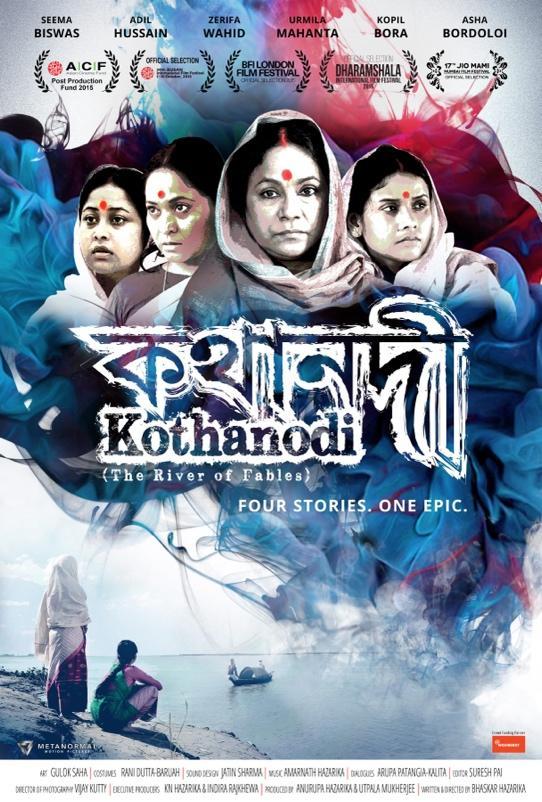

Poster for Kothanodi (2015) directed by Bhaskar Hazarika, which is an adaptation of Burhi Aair Sadhu, a popular collection of folk stories penned by Lakshminath Bezbarua.

The revival of Assamese cinema in the contemporary is rooted in its contentious past and aspirational present; its immense interaction with new technologies creates cinemas replete with a sense of homegrown aesthetics borne out of the realisation of the state’s perennial underdog identity. Assamese films had a slow start and attracted fewer audiences. Many factors contributed to the shunted development of the film culture in the state. This included the diversity in language and the ban on Hindi films. The latter crippled the local film-going culture. The Hindi juggernaut had eaten up all the regional films in its way. Bombay cinema found its influence even in cheaper, local popular films. These productions often used the Bollywood template to create fast films in order to keep the film market afloat.

Poster of Bokul (2015) by Reema Borah, which follows a young man’s return to his hometown.

In this environment, there emerged a motley band—consisting of both autodidacts and film-schooled individuals—who broke through the stunted cinema history of the region to generate a formal and aesthetic style. A significant contribution has been the popularity of DIY practices, which are responsible for the production of some of the most talked-about films from the region, specifically from Assam in recent times.

The last decade can be considered one of the most prolific periods in Assamese film production. Many of them are recognised and awarded for their excellence both nationally and internationally. One common factor in all of them has been their funding source, at least for their first venture. Filmmakers including Bhaskar Hazarika, Reema Borah, Kenny Basumatary and Rima Das, to name a few, all crowdfunded or self-funded their first films. Often, the success or visibility of their first film has led to them acquiring more funding for their subsequent ventures, but this, of course, is not the trend. I highlight the case of two of these films, namely Basumatary’s Local Kung Fu (2013) and Rima Das’s Village Rockstars (2017).

Still from Local Kung Fu 2 (2015), directed by Kenny Basumatary.

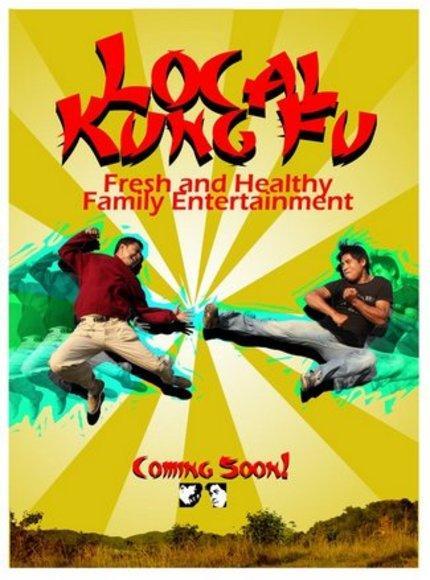

Basumatary’s individuality rests in his self-taught, self-made approach. This is best expressed in LKF not only in terms of its production but also its innate sensibility and DIY aesthetics. When asked, in an interview, how he managed to direct a film considering his lack of academic and professional training, he immediately replied, “YouTube and Google,” signalling towards the instructional role of online spaces despite the divisive politics that get re-imprinted onto digital visual cultures. For instance, journalist Ankur Pathak attributed his DIY sensibility to “creative austerity.” This creative austerity has been facilitated through digital technology—cheaper digital cameras, affordable editing software, tutorials from YouTube, etc. Shot on a minuscule budget of 90,000/- INR with the support of extended family and friends as actors, assistants and line producers, it can be inferred that a film like this would not have seen the light of day without digital intervention.

Poster of Local Kung Fu (2013) by Kenny Basumatary.

Basumatary narrates how, even after his script was among the top six at the Sankalan script lab-cum-competition, held by the Mahindra group in Mumbai, LKF could not get a financer. Tired of waiting for someone to fund his film, Basumatary decided to shoot and produce the film on his own after his mother gave him a part of her savings. Following a screening at the Osian Festival, the film circulated extensively through social media conversations. This, along with word-of-mouth, drew a cult following for the film, which led to the the film’s wide circulation across pirated networks. Later, Shiladitya Bora, the director of one of India’s largest film distributors, PVR, released it on PVR Director’s Rare.

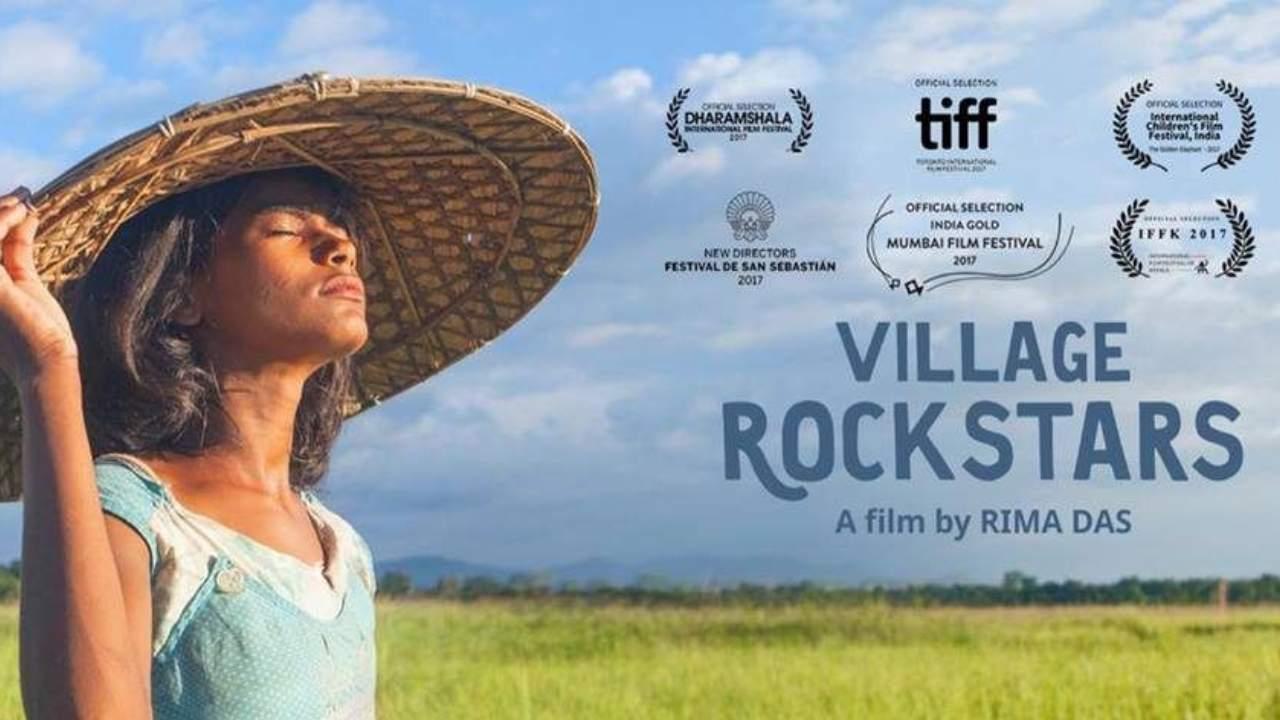

Poster of Village Rockstars (2017) by Rima Das, a coming of age story around a young girl’s ambitions amidst the burgeoning turmoil in her village.

Similarly, Rima Das’ Village Rockstars was produced with the director-producer’s resources. From the costumes to the film's editing, Das was single-handedly responsible for the film beyond her role as the director. The filmmaker went on to produce another film, Bulbul Can Sing (2018), which the audience received warmly. Bhaskar Hazarika’s Kothanodi (2015) was also produced solely on crowdfunded sources without the backing of any formal organisation.

Poster of YouTube series Kritikal Kouple. (Source: India Today.)

The homegrown cinema of Assam required certain provisions for its mobilisation, the primary being the easy manipulability of the digital medium. It allowed for cheaper technology to make films; YouTube and Google provided easy access to learning resources; crowdsourcing became a convenient way to get funds; and social media allowed for broader promotion. These factors together allowed the filmmakers, producers and distributors to exercise and thrive in their cultural identities, local ethos and practices, thus heralding a return to the homegrown.

To learn more about Assamese film and new media cultures, read Anoushka Prasad’s review of Priya Naresh’s documentary Small-Time Cinema (2022) and Sagorika Singha’s essay on the influencer as content creator in the case of Dimpu Baruah.