While We Watched: “Godi Media” and Ravish Kumar’s Dissent

Recipient of the Peabody Award 2024, Vinay Shukla’s documentary film, While We Watched (2023), is a sensitive portrayal of former NDTV journalist Ravish Kumar, amidst the rise of what Kumar labels pejoratively as “Godi Media.” Quite literally translating to lapdog media, Godi Media refers to the meteoric rise of sensationalist print and news channels over the last decade, and their role in driving public perception in favour of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s dangerous religious fundamentalism masked as nationalism. Set in the years preceding the 2019 general elections and its immediate aftermath, While We Watched depicts the transformation of the Indian public from viewer to spectator, and of TV news channels from truth-seekers to purveyors of perverse enjoyment.

.png)

Ravish Kumar holds fort, persisting in drawing the viewer towards the truth.

While We Watched follows Kumar and his team’s efforts to air NDTV Hindi’s much-loved flagship weekday prime-time show during a dark period in the history of Indian TV news media, which was busy shoring up the recruitment drive of Indian youth into the Modi government’s fascist project grounded in a polarising discourse of Hindu-Muslim antagonism. Shukla’s documentary is a testimony to the importance of bearing witness and the necessity for the emergence of a new political subject, especially when it seems impossible. To see this journey from the vantage point of the 2024 Lok Sabha elections—the first election since 2014 in which the BJP has not won enough seats to form government on its own—is to reinvigorate the potential and responsibility of not only the journalist but also, and in equal measure, the viewer, for the protection of that prized fundamental democratic principle—freedom of thought. For, as Kumar mentions in his YouTube video titled “The first time that Modi will face a Leader of Opposition in Parliament”, this is “the first election in which the Indian public gave the nation not a government but an opposition.”

NDTV Hindi team producing Kumar's weekday prime time show.

The hostile environment in which Ravish Kumar and his team were trying to conduct honest journalism and adhere to the truth is depicted through a juxtaposition of NDTV’s struggle to procure bites owing to a lack of reporters, with an intelligent selection of short clips capturing nationalistic jingoism portrayed across mainstream national news channels. This is interspersed with footage of death threats to Kumar, ranging from accusations of being an “anti-national” to “urban Naxal”—which gained currency in 2018 in the wake of the crackdown on activists in the Elgaar-Parishad case in Maharashtra and has since been used to damn any dissent against the Modi regime—all driven in no small measure by the same media that Kumar suggests must be scrutinised for betraying the Indian public. The effect is to serve as a painful reminder of the speed at which reason deteriorated as the raison d’être of journalism.

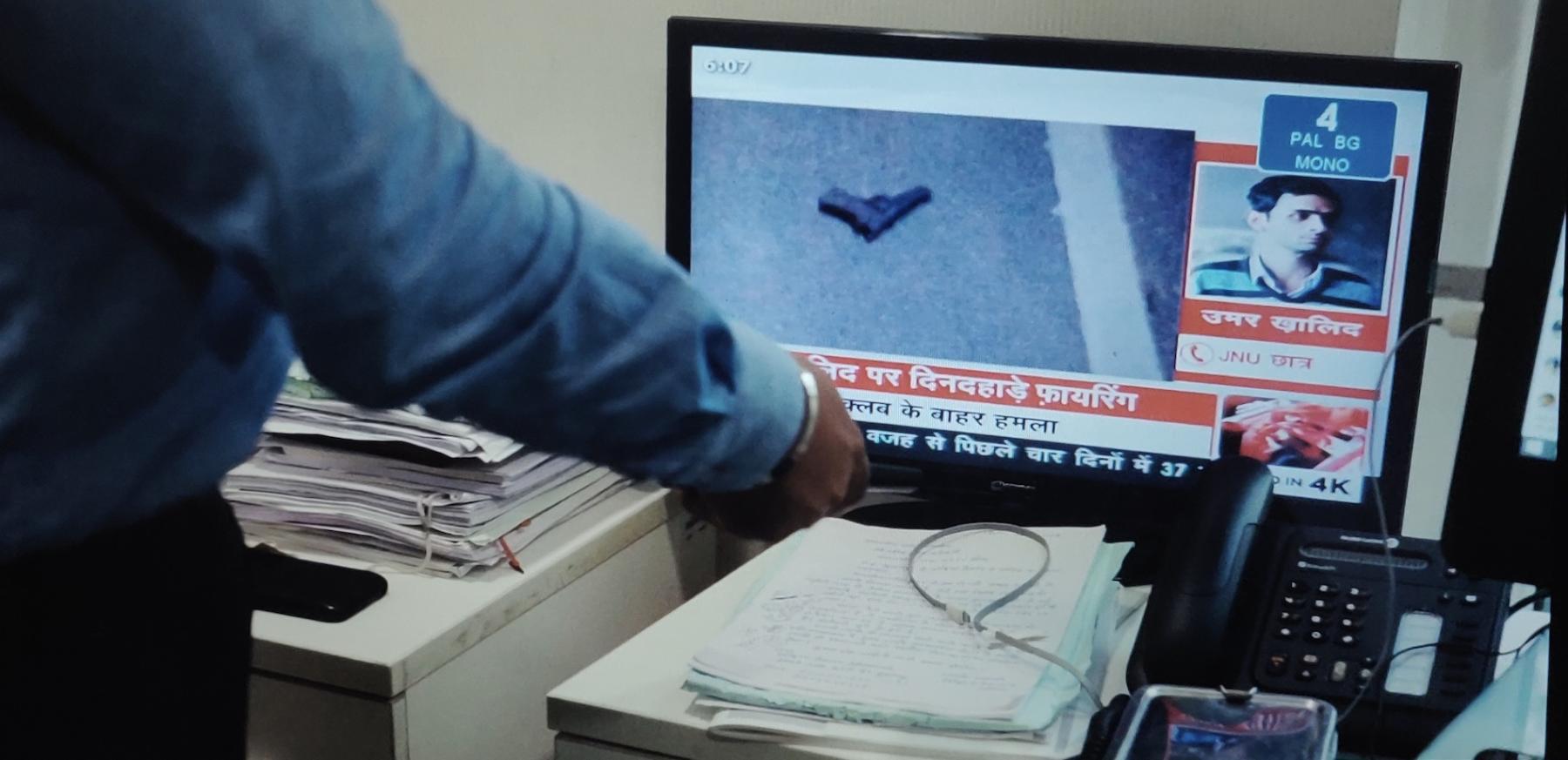

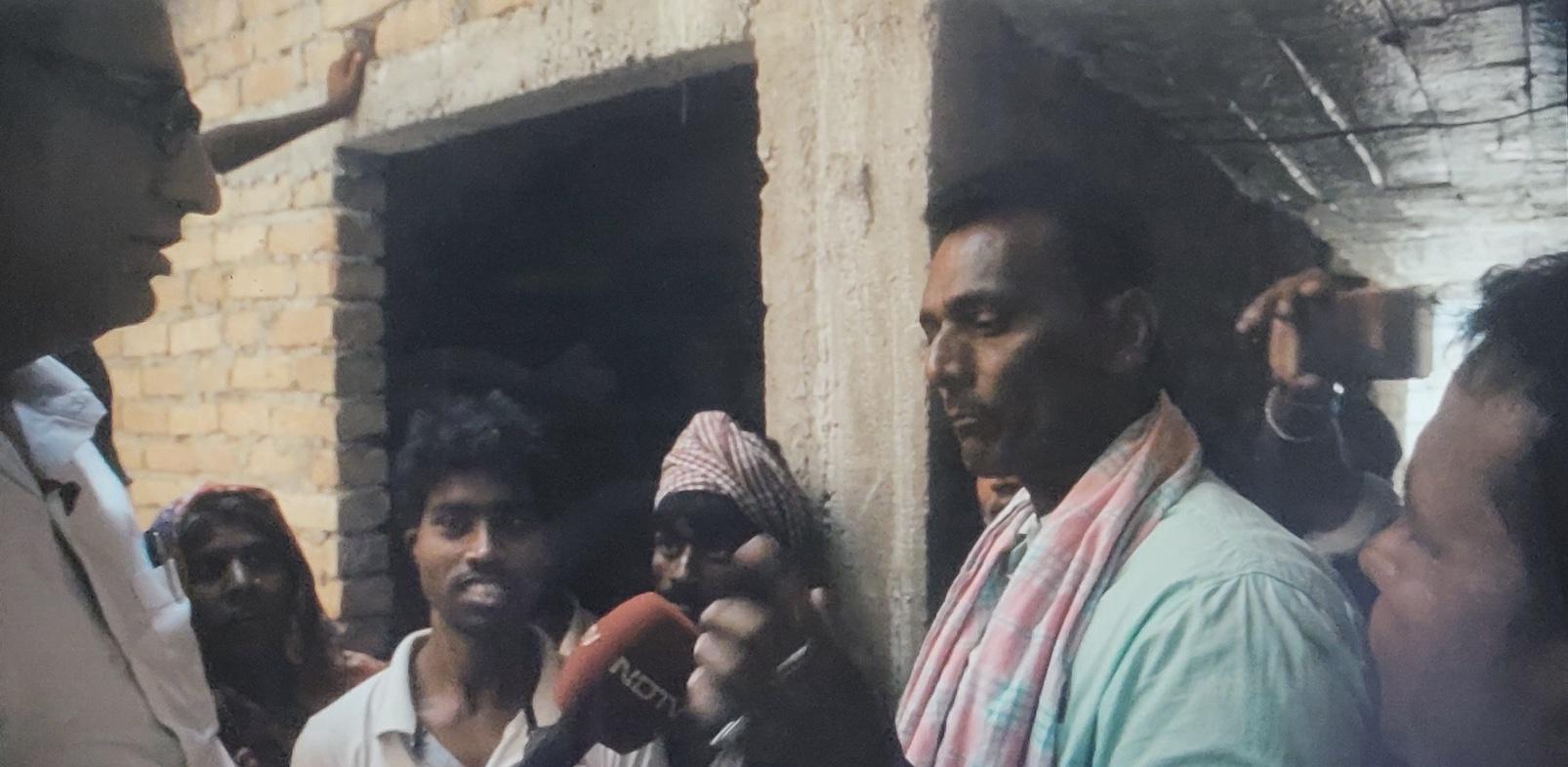

The gradual realisation of the adverse impact of this “Godi media” on the public mind and on one’s own ability to be a journalist with integrity unravels in the transition of affect from being appalled, disgusted, shocked, helpless, and yet determined to speak the truth. A turning point is the attack on Umar Khalid in broad daylight at the Constitution Club in 2018. Despite high security, and the subsequent admission of responsibility by two youngsters on camera, which, as the film shows, Kumar notes astutely is symptomatic of the media “telling people it is okay to kill somebody.”

Ravish Kumar finds out about the attack on Umar Khalid.

An evocative scene from the film between Kumar and his daughter becomes the metonym for his decision to strengthen his voice. About to write his script for the evening, and still deliberating upon the possible consequences of speaking the truth at a time when no other channel is covering this story, Kumar asks his daughter on video call if he will ever be able to learn how to sing like her. She replies in the affirmative, but with a condition: “You must practice every day… Keep trying… Only when your voice becomes strong will you be ready to learn.”

In a tender moment following despair, Kumar takes inspiration from his daughter.

The transformation from witness to subject is most notable in Kumar’s warning to the Indian public that Godi media is utilising TV to control their minds, as they are torchbearers of this propaganda. It is thus his job to alert the public against such lies and deception before they become complicit in the violence and destruction of democracy. Invited to a university for a talk on "Higher Education and its Challenges", Kumar cautions the audience against self-censorship resulting from a fear of being called a “traitor.” He insists that such fear is the beginning of the end of democratic values. Disturbing the taken-for-grantedness of the category of the “nation,” now routinely mobilised by the media to drive nationalistic pride and insecurity, he asks the audience, “Is this the India you dreamed of?” In a reversal of agency from journalist to viewer, Kumar turns the dictatorial demand, “The nation wants to know” into a question of political desire: “Is this the nation you want?”

Met with a resounding “no,” the scene is one of a few moments of hope among an otherwise predominant story of despair. The sense of doom is felt most perhaps during the frequent cake-cutting ceremonies at the NDTV newsroom, announcing the departure of yet another colleague, with Kumar wondering if anybody will be left in the department the following day. Yet, this is a story of insistent and tender care—an understanding for those who decide to leave, and an acknowledgement of those who choose to stay. It is a story of everyday resistance, in the blind faith that the work of honest journalism and of telling the truth continues to have meaning despite the injunction to “perform or perish.”

Senior Producer, Swarolipi Sengupta, whom Kumar calls the nation's best producer, decides to leave.

But the camaraderie of the journalistic fraternity is also evident in quieter moments. During the purported targeting of NDTV following allegations of financial malpractice by founders Prannoy and Radhika Roy, as Kumar laments the loss of an entire floor of colleagues, the (former) CEO Suparna Singh, putting on a brave face, says, “It’s just a smaller office, but the work will continue. We will do it together.”

Despite expressing the desire to quit several times, it is these moments of reassurance—from colleagues and Kumar’s astute and supportive partner Nayana—that propel him forward towards his resolve. This culminates in the definitive emergence of a new political subject who must decide how to act in the present, even as the past is untenable and the future uncertain. When asked by the editor of a small newspaper if he must sacrifice his principles for his job, Kumar ponders briefly, before eventually responding, “I will not do what the government wants me to do. The time has come to choose between journalism and keeping one’s job. No fight is without a cost.” That Kumar knew the stakes of this battle are not between victory and defeat, gain and loss, subject and victim, but the continual, renewing struggle for the making of a political subject, is evident from his acceptance speech of the Ramon Magsaysay Award in 2019. “Resistance is not a matter of choice. Not all battles are fought for victory. Some are fought simply to tell the world that someone was there on the battlefield.”

Kumar accepts the Ramon Magsaysay Award 2019.

In Ways of Seeing, John Berger says, “Seeing comes before words… The relation between what we see and what we know is never settled… We only see what we look at. To look is an act of choice.” It is this possibility that Kumar invokes when he says,

“As long as there is even one viewer who sits on the sidelines and analyses, until then there is a possibility for facts, for truth to survive. Nobody can count you. I’m called Zero TRP anchor. But you are a viewer and you are not zero. A viewer is made by seeing, the patience of seeing, and the ways of seeing. Keep seeing.”

Kumar remains focused on the Indian voters' key issues, namely roti, kapda, makaan (food, cloth, shelter).

It is through the struggles and choices of an ordinary man—"I am no saint,” Kumar says in the film—with fears and anxieties but a commitment to truth, that the film examines the act of seeing as a formative process that enables Kumar’s own metamorphosis from subjective anchor to political subject. In doing so, it renders within the reach of the Indian public the possibility to bear witness and cultivate ways of seeing as political praxis.

Kumar’s faith in the continuing presence of even a single Indian viewer who has not yet been converted into a spectator, as evidence of the potential for political change, has come to bear in the creation of an opposition for the first time since 2014. His recurring and persistent insistence on drawing the viewer back to the crises of the present—of unemployment, farmer distress, food scarcity, water shortage, and a lack of access to education—remains reflective of, if not instrumental in, the Indian voter’s return to questions of concrete, material existence in the face of an increasingly oppressive regime of authoritarian capitalism. Perhaps it is no surprise then that Kumar’s YouTube channel now attracts over 10 million viewers, the number of people who lost their jobs in 2018. Could this be a turning point for the redirection of the unemployed from vigilantism in service of the sectarian project to new political subjectivity?

Kumar insists that truth can survive as long as there is even one viewer.

To learn more about films responding to the contemporary political context in India, listen to Ashish Rajadhyaksha’s public lecture drawing from his book John-Ghatak-Tarkovsky: Citizens, Filmmakers, Hackers (2023).

To learn more about critical media practices, read Ankan Kazi’s essay on Navina Sundaram’s archive and Senjuti Mukherjee’s interview with Sanjay Kak on his book Witness: Kashmir 1986–2016: Nine Photographers (2017).

All images are stills from While We Watched (2023) by Vinay Shukla. Images courtesy of the director.