Mani Ratnam’s Bombay: The Politics of Censorship and Stereotyping

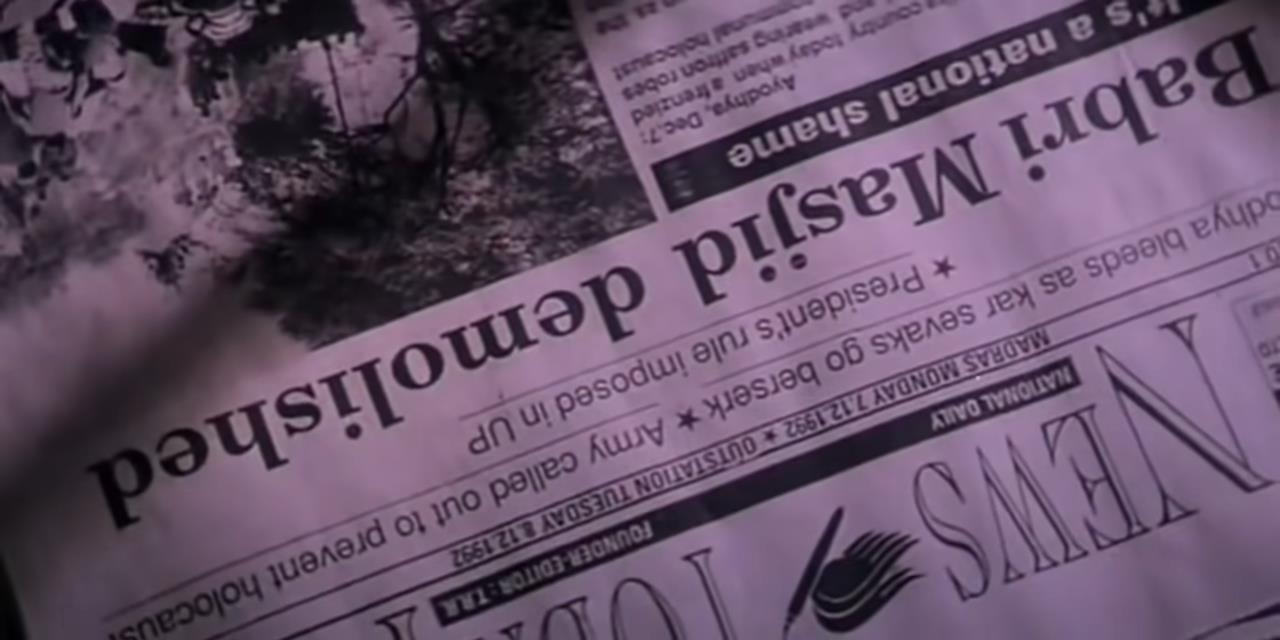

The first part of this essay examined the gendered politics of Mani Ratnam’s Bombay (1995), which dramatises the rising communal tensions in India during the early 1990s. The film, which follows the marriage and interpersonal relationship between Shekhar and Shaila, perpetuates embedded stereotypes about the Muslim community in the city. Bombay further reinforces negative stereotypes of the Muslim community through its visual depictions, such as a sequence where men in white-filigreed caps are shown present at riot sites, portraying them as initiators of violence with swords and cleavers after the Babri Masjid demolition.

Basheer slaps his daughter, Shaila Banu.

Narayanan shouts at his daughter after she says, “Shaila is a nice girl.”

The two paternal figures in the film, Shaila’s father, Basheer, and Shekhar’s father, Narayanan, aptly inhabit the ‘us’ and ‘them’ dichotomy portrayed throughout the film. While both function as dominant patriarchal figures in the plot, Basheer’s actions are often presented as more aggressive and violent when compared to Narayanan. After Basheer learns about the secret letters from Shekhar to Shaila, he drags his wife to the courtyard by her ear. He later confronts Shaila and slaps her violently after she refuses to accept his plea to not fall in love with a Hindu man. On the other hand, Narayanan only points his finger at his daughter, who disregards his authority when she claims, “Shaila Banu is a nice girl."

Basheer aggressively marches towards Narayanan, holding a machete.

Narayanan tries to de-escalate the crowd.

The film further visualises this dichotomy by strategically positioning Muslim characters in different scenes. Their reactions portray consistent, negative stereotypes to consciously and cinematically foster biases. These biases are directly reflected through different angles during an encounter between Narayanan and Basheer, making the film’s division of physical aggression versus verbal aggression apparent. The first confrontation happens when Narayanan goes to Basheer’s house after learning of Shekhar’s plan to marry Shaila. Basheer draws out his machete twice in the scene, despite Narayanan’s purely verbal threats of bloodshed. Later, Narayanan tries to calm the crowd and proclaims, “It is their personal matter,” but the camera still lingers on Basheer holding a machete. In another sequence, when Naryanan and Basheer return from their respective religious prayers, Narayanan faces threats from Muslim men, but Basheer does not.

References to such stereotypes of violence through cautious angles and close-ups construct Muslims in the film as impediments to a secular nation. Iqbal A. Ansari’s book Communal Riots: The State and Law in India, based on a 1983 report by the Minorities Commission in India, suggests that prejudices held primarily by police forces towards Muslims included the belief that they are “excitable” and “irrational,” while Hindus are “law-abiding” and “cooperate with the police” in controlling communal violence.

Narayanan threatened by Muslim men after religious prayer.

Under the garb of promoting a vision of ‘secularism,’ Bombay adheres to an institutionalised communalism. This is evident from the erstwhile Shiv Sena’s leader Bal Thackeray’s direct interference in the release of the film and a pre-screening held for him and top police officials ahead of its release, which was in direct violation of the 1952 Cinematograph Act. Even India’s prime institution for film regulation, the Central Board of Film Certification, was not left uncontrolled or supervised. As Rustom Bharucha outlines in his seminal book In the Name of the Secular: Contemporary Cultural Activism in India (1998), the most violent incident between Hindus and Muslims since India’s independence in 1947 had to be reviewed by a Hindu fundamentalist politician, who was arguably most responsible for instigating the violence. Bharucha writes, “Within the history of censorship in world cinema, this must surely be one of the most insidious affirmations of how violence can be legitimised by its own political agency.”

Mani Ratnam removed two scenes from the film after Thackeray’s objections: the first one is of Tinnu Anand’s speech while he distributes bangles to his followers after the murder of two Mathadi workers. In his speech, Anand speaks of ethnic cleansing and saving the city of Bombay for only Maharashtrian Hindus—a reference directly taken from an actual speech given by Bal Thackeray. The second scene shows Anand's repenting after the riots, which indirectly suggests Shiv Sena’s complicity in the riots, contrary to the retaliation attack spearheaded by the leader. Thus, the intentional cuts in these scenes project Muslims as the sole instigators of the communal strife and Hindus’ acts of arson and violence as one of mere retaliation.

Newspaper clipping of Babri Masjid Demolition, in a still from the film.

Man cries out, “Hai Allah”.

Muslim men offering namaz run out with their swords.

Despite its documentary-like presentation of the events of 1992-3, including elements like newspaper clippings, historical references, and proximity to actual events, Bombay hugely alters the facts and narratives in its dramatisation of the events. In the first riot sequence, soon after the newspaper headlines of the Babri Masjid demolition are reported, Muslim men are depicted as violent aggressors, brandishing swords and abandoning prayer to join in vandalism and arson. Throughout the entire first segment of the December riots, the film portrays Muslim men vandalising shops, setting fire to the city, abusing police officers and killing Hindus, while the latter community only appears briefly and often in non-violent contexts.

Similarly, in the second segment, the camera meanders through a cramped neighbourhood of Bombay, finally resting at a house with the Swastika symbol on its front wall. That house, as well as our protagonist Shekhar’s house, is set on fire by a few Muslim men, with the film only depicting some armed Hindu men sans violent action.

A house set on fire by a few Muslim miscreants.

The cumulative effect of these scenes sets Muslims apart in the film as the primarily violent aggressors, justifying every action taken to control them, including the police’s open fire. In response to the Bombay riots, the Indian People’s Human Rights Commission appointed a Commission of Inquiry in 1993, which investigated the role of the police. According to a report, The People’s Verdict (1993), by retired justices S.M. Daud and H. Suresh, based on the testimonies of numerous witnesses, the police were frequently bystanders and supported the Hindu aggressors during the violence. The report states, unsurprisingly, that many “...police officers and constables openly said that they were Shiv Sainiks at heart and policemen of a supposedly secular State by accident.” During the riots of December 1992, Amnesty International reported significantly larger Muslim deaths when the police fired at the mobs in Bombay. Based on post-mortem examinations, 90% of the victims sustained injuries above the abdomen, indicating that the police shot to kill, rather than to maim or injure.

Cinema, as a mass medium, ideologically plays a role in shaping stereotypes of communities and perpetuating the risk of misrepresentation. By reading the inherent strands within the visual and narrative of Bombay, one sees the pitfalls of an “institutionalised” secularism, one that adheres to a vision of the State as dominated by a singular religious, caste identity. On the one hand, Bombay tries to promote universal, humanist secularism while at the same time perpetuating negative stereotypes against the very same community. The film’s dramatisation of communal strife, changes in narration, linearity, censorship, and strategic placement of Muslims as the hosts of inherent violence and riots underscore its blind spots.

In case you missed the first part of the essay, read it here.

To learn more about the complex history of communal violence in the subcontinent, read Ankan Kazi’s reflections on a panel discussion titled “Image & Memory” and Najrin Islam’s review of Ritesh Sharma’s Jhini Bini Chadariya (2021).

All images are stills from Bombay (1995) by Mani Ratnam, courtesy of the director.