The Coca-Cola Fascination

2000

She took the first sip of the carbonated drink. A wee dram perhaps. An elliptical galaxy floated in her glass. Tiny air bubbles fizzed upwards into the quiet summer afternoon. They appeared and disappeared like twinkling stars upon the dark surface of the liquid. A brief pause and she slurped a mouthful this time. A galactic secret travelled inside her body. Her tongue must have tingled. The cold sweet drink must have fizzed its way down her throat, refreshing her weakened tissue linings. Wrinkled like an empty sack, loose flesh that hung under her chin must have briefly forgotten the weight of a lifetime. Her stomach carbonized as she relished the beverage heartily.

Changi Hey Vey! It tastes great!

She nodded while sitting on the floor, beaming suddenly with a broad smile as appreciation glinted through her eyes. Everyone laughed seeing Amma’s reaction to the beverage of the century.

1990

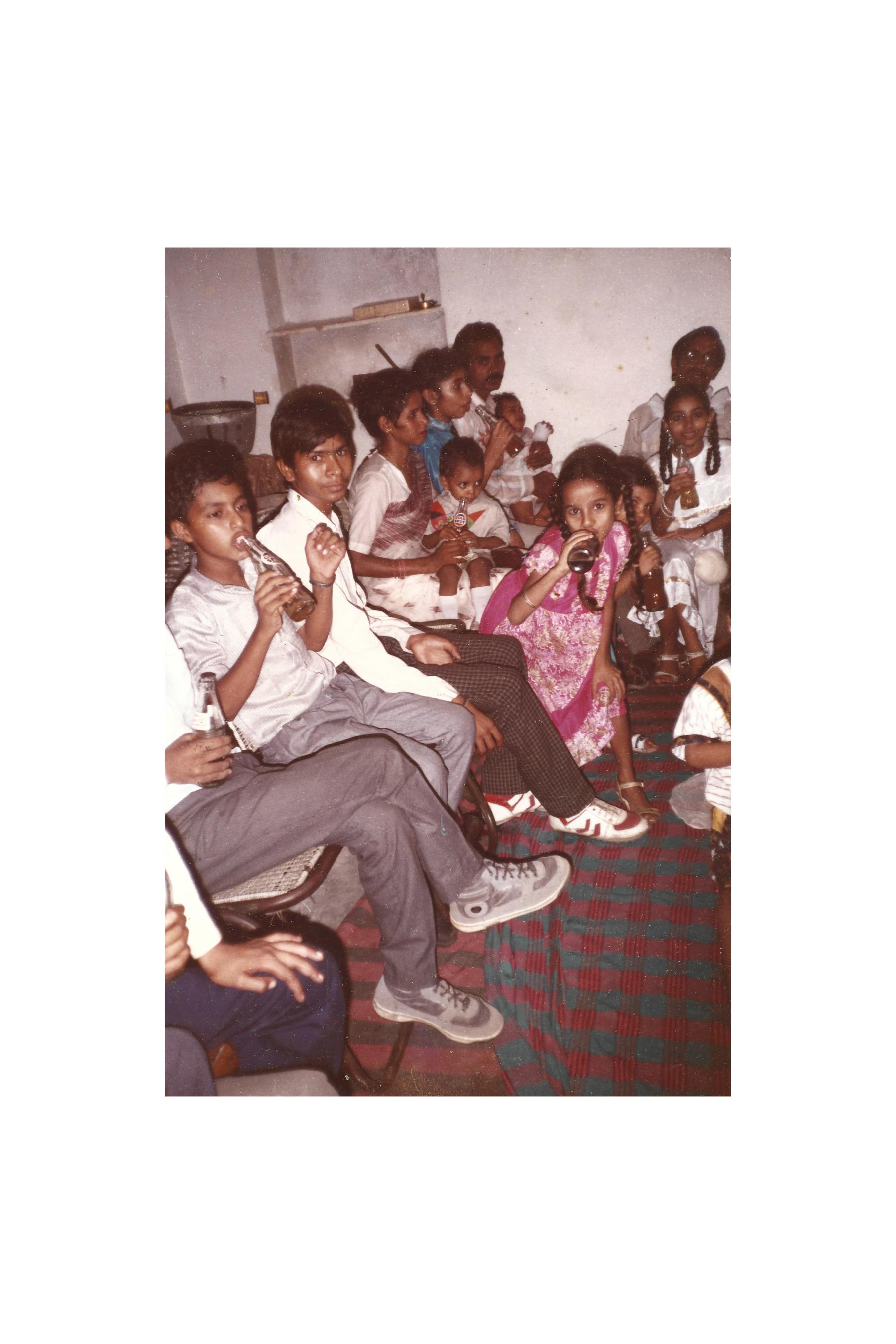

A group of relatives from different generations, roughly thirty to forty people can be seen accommodated in a small room, which seems to be the living area of my late grandparents’ house. In a set of photographs from my family albums, some are sitting on a divan, while others are perched on chairs lined against the walls that have now ceased to form any enclosure. They overlook others who are scooched down on a striped carpet spread out in the center of the room. Some are leaning against the walls and others are accommodated with those nearby. They can be seen, in these photographs, partaking in moments of leisure and laughter, conversations and caresses as if sharing an age-old secret of the family. Held together on a foreign land with the broken thread of the family line fifty years after the Partition, reforming, resuscitating, rebuilding—which perhaps is more evident to them, unlike to the viewer of these photographs. Adorned in vibrant clothing, children and adults alike hold curvaceous bottles of glass: Gold Spot, Thums Up and Limca scripted on them, soon to be succumbed under the infamous umbrella of the brand Coca-Cola. The zingy logos visible through their grips as symbols of their survival and as objects of their status shine. One for each member of the family, relishing the refreshment of the special evening—my aunt’s engagement ceremony.

2004

One might say that the year 2004 was 1492 for my family. The beginning of the so-called New Age. The era of Enlightenment. The origin of photography.1 The year of infiltrations. Papa brought home a manual fizz-maker; A yearly gift to the factory staff where he worked as an administrator. Due to the mounting debt over the last few years, India’s agricultural state’s Sheet Glass Pvt Ltd urged its employees to buy bottles of glass and make their own colas. So, Papa pulled the lever down and added pressure inside the container, while year by year, the company passed through financial crunches. Our family’s first mobile phone was bought a couple of years later in 2006 from Maa’s income. A second-hand Nokia 2310. Kept under the cover of the refrigerator, it remained undisclosed for days. Soon Maa would phone her mother, sisters, and friends without hesitation, unrestrained from the lurking gaze of the joint family and those listening earnestly to her conversations through the landline extension in the other room, like ghosts. As Papa maintained pressure in the vessel, airy bubbles emerged victorious from the clear water and gas slowly dissolved into the liquid, as plastic increasingly became the profitable choice of the Coca-Cola company and Maa went to work with a fistful size of freedom hidden inside her purse, as rivers choked on toxic disposables and birds confused shreds of plastic for food, as over the years Maa stored on her phone selfie snapshots with a smile and unbraided hair that was relieved lastly from the netherworld of the family albums, as holy cows impassively altered their taste palettes and politicians exhibited in turn holy concerns—the middle class of the new liberated India gulped, burped, farted, fascinated and laughed, discreetly or in groups, at the novel discoveries of their bodies.

2013 and early 1900s

‘The Small World Machines’ initiative of the Coca-Cola Company in 2013 provided a digital portal to the people of the two countries across national borders.2 Aimed at the middle-income group of India and Pakistan, families came face-to-face through vending machines equipped with full-length webcams. They waved, touched hands, drew symbols of peace and smileys, and imitated dance moves through the live imagery that was broadcast on its digital screens. People took back happiness and 200ml of Coke as giveaways.

Around the time of Partition, during the second World War, Cameras, Coca-Cola, Cameras mounted on guns, and hand grenades became overtly accessible.3 Freedom became ideological, portable, hand-held, pocket-sized, and saleable. The celebration of the infamous Coca-Cola traded secrets with the celebration of photography. Soldiers and glamour girls grinned in a similar manner through the posters of war and advertisement campaigns. The Gun Cameras got equipped with the grip of a pistol and the trigger for the shutter allowing the gunman to look through the sight of an open rifle as substituted for the customary viewfinder – a gaze developed to literally shoot, kill, and record. The air inside the tiny bubbles tickled by the smoke of the bombardments reinforced the grains of the black-and-white images. Photography contributed to and continued to play an integral role in the sustenance of neo-liberal democracies, through both advertisements as well as political propaganda, making photographs not merely a tangible marker of past and history, but a representation of people’s desires enamored with the concept of taking pictures imbued somewhere by the market itself, while explicitly claiming to be of the people, for the people and by the people.

1992 - 2013

Baba always rejected the idea of a drink concealed in a bottle. An American product monopolizing local markets. He was not a communist.

He passed away in the winter of 2013, insomniac the entire night staring ceaselessly at the broken ceiling, supported by wooden beams burrowed with bugs and mites, neither reflecting in nostalgia nor remembering his life’s achievements, failures or mishappenings, instead his eyes carried acute disagreements with the world.

2003

Sunny was dark-skinned like the drink itself. His family lived on the periphery of our neighborhood. My brother and I spent many evenings with him on our terrace. Eating black plums that had fallen from the Jamun tree. Our tongues would turn blue like dusk. Our mouths would get dry like cloth. We would then quench our thirst by guzzling down copiously the restless drink. Five rupees a bottle. I scored significantly low grades that season. Sunny stopped coming soon after the result day. Though his father continued to pay visits to our house to unclog the toilet.

2022

Six years after Amma’s parting, I revisited Garhi, a small neighborhood where we all grew up. My uncle wanted to see me, Papa insisted. So one spring evening, we finally went to visit his elder brother. Baba’s chakki was now my uncle’s godown and what used to be on the floor above—our home—was devoured by the high ceiling of the new godown structure. Its color that of the cement. Sacks of grains and flour stocked and piled on top of each other disappearing into the endless ceiling. In this dust lingered our home. The rigid mass of the building block stood unmoved and unrecognized, disembodied from our memories of the place. My uncle asked for the thandas. Meanwhile, we waited in silence, street-side, in the evening blue, which on the lane of my own childhood felt like the edge of the world.

1990

The earth dragged itself around the sun. A bird fluttered against the wind. An undiagnosed ailment wrapped the organs quietly under Amma’s skin. At generational distance, a baby girl was born with a heavy heart. The grave, so tender. Witnessed by a son through the night: Baba leaving his body, part by part. In these images, my aunt is being fed sweets and values. Gossip, chatter, and laughter of a time before my own existence can be heard through these photographs. Overlooked is the one sitting on the floor, who could make a part into a whole. Surrounded by children, as always, the mother. Obstructed by adolescent faces looking straight into the camera. Behind them, the old woman undisclosed. Subsumed by her motherhood, she lived close to a hundred; a being, forgotten and left unknown. Her essence felt like the fragrance of skin. Fleeting. Impalpable. Inaccessible.

Author’s Note: Through a set of family photographs, The Coca-Cola Fascination illustrates a collection of eight short narratives revolving around the soft drink while moving across time and distance. One foot wedged into the past, the post-partition family from Haryana, India is looked at through these photographs where freedom and change askew and take form in a capitalist setting. These intimate moments express the entanglement of photography, freedom, and capitalism in a domestic environment tainted with loss, migration, caste, and patriarchy.

Image details: All photographs were taken at the engagement ceremony of the writer’s aunt. Photographer unknown, Haryana, India. Date unknown, c. 1990s, Digital Scan, Analogue Photographs, 8.3 x 12.6cm each. Images courtesy the writer.

Jatin Gulati is a writer, visual artist, and educator with a formal education in architecture. His works are informed by various aspects of ‘absences’, though most often driven by its traces in the immediate, personal, and lived experiences. His interest in thinking photography stems from the role of images as myth-making for socio-political and familial ideologies. He graduated in photography from Pathshala South Asian Media Institute, Dhaka, and his work incorporates mediums such as photographs, archives, text, and digital environments. He teaches contemporary photography narratives at the School of Media, Arts & Sciences, Srishti Manipal Institute, Bangalore.

Endnotes:

1 Azoulay, Ariella Aïsha. Potential history: Unlearning imperialism. Verso Books, 2019. For an introduction, read a series of her statements published under the title “Unlearning Decisive Moments of Photography” to understand potential history of photography. She begins her enquiry by proposing that we “imagine that the origins of photography go back to 1492”, which is way before the invention of the camera machine. Azoulay, Ariella Aïsha. “Unlearning Decisive Moments of Photography”, Fotomuseum Winterthur (Sept – Oct 2018), https://www.fotomuseum.ch/en/series/unlearning-decisive-moments-of-photography/

2 “Coke’s enduring legacy of Inclusive Advertising: From ‘Hilltop’ to ‘America’s Beautiful’”, Published by the Coca-Cola Company, 2017. Retrieved on 4 January 2023, https://www.coca-colacompany.com/news/cokes-enduring-legacy-of-inclusive-advertising

3 See the footage captured by the gun camera mounted on Lt Col Jack Bradley’s P-51 Mustang between December 1943 to January 1944, published on Texas Archive of the Moving Image. Item: The Lt Col Jack Bradley Collection, no. 2 - Gun Camera Footage, 1943-1944 (B/W, Silent), https://texasarchive.org/2009_01486; “Hythe Mk III Gun Camera”, Forgotten Weapons. Retrieved on 4 January 2023, https://www.forgottenweapons.com/accessories/hythe-mk-iii-gun-camera/