A Very Old Machine: On Jahnavi Phalkey’s Cyclotron

In 1939, Ernest Lawrence won the Nobel Prize in Physics for “the invention and development of the cyclotron and for results obtained with it, especially with regard to artificial radioactive elements." It announced the arrival of high-energy physics as a significant discipline of research, attracting greater funding from state institutions and grant-generating bodies. The new atomic age was intricately constructed by the research agendas of several brilliant scientists, many of whose names have become common knowledge since then. More importantly, however, the state’s investment in co-opting this new research for its own security apparatus went a long way towards entrenching the discipline as an essential one for our time.

Documentary filmmaker and science historian Jahnavi Phalkey attributes the growth of high-energy physics to this “academic-industrial-military complex” that put nuclear research at the centre of the state’s agenda as a means of securing themselves during the Cold War armaments race. The arrival of a pre-used cyclotron in a “regional”, North Indian university is critically framed by Phalkey in her film Cyclotron (2020) as the conduit for various interwoven narratives of political and social transformations. The film tracks the growth of postcolonial scientific cultures in India in conversation with their better-funded Western counterparts. Cyclotron’s tracing of the expansion of such local scientific cultures around a large, user-intensive machine allows it to contend with nationalist, myth-making narratives of popular series like Rocket Boys (2020–). In the latter, scientific agendas are embodied by outsized personalities in conflict with each other over the “right” way towards a modernity in perfect alliance with Indian nationalism. The history traced by Phalkey is more difficult—full of ruptures, denials, obstacles and, ultimately, the threat of obsolescence even before the machine can realise its full potential.

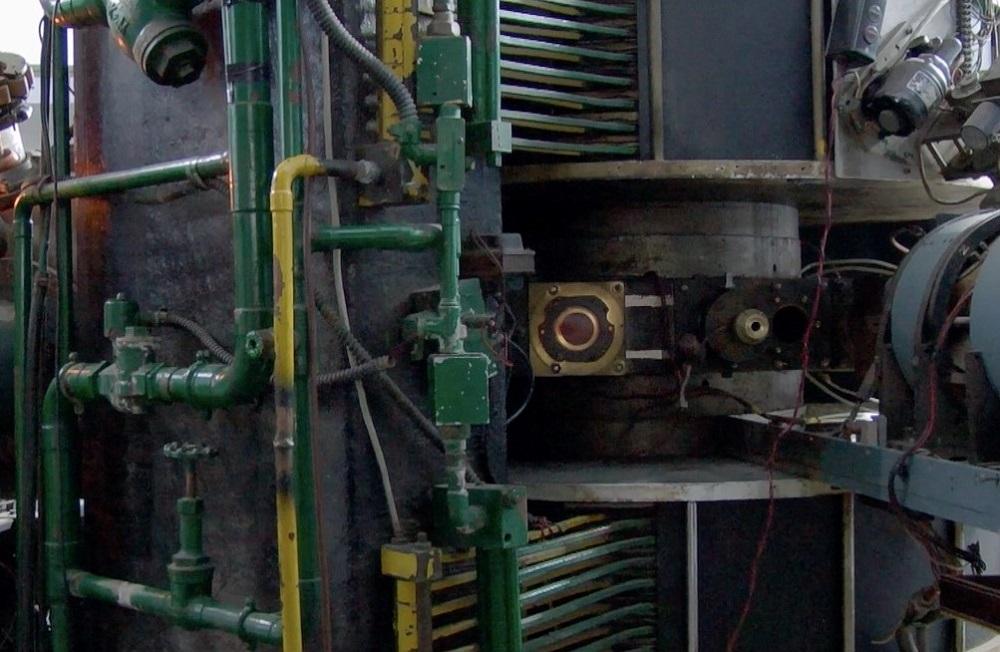

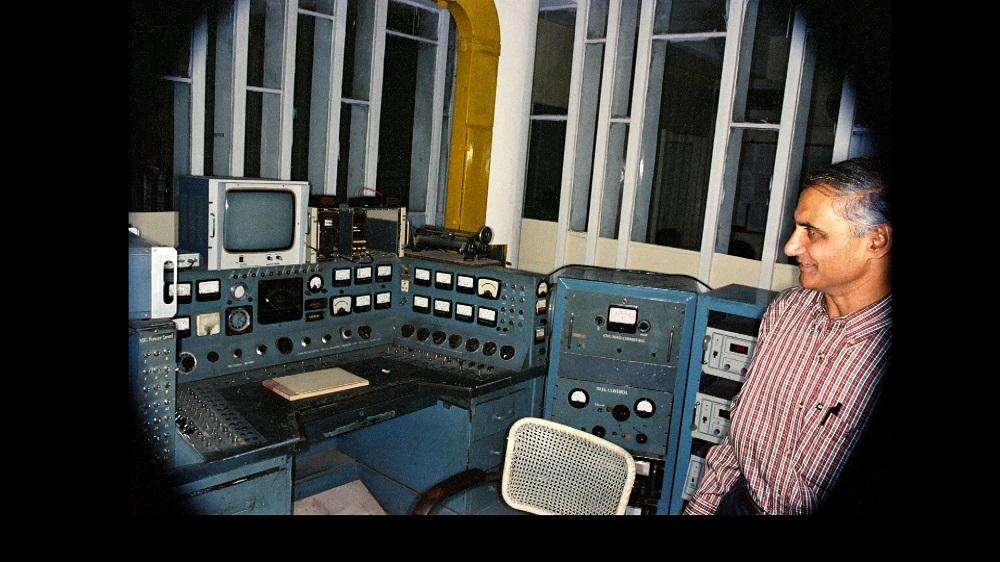

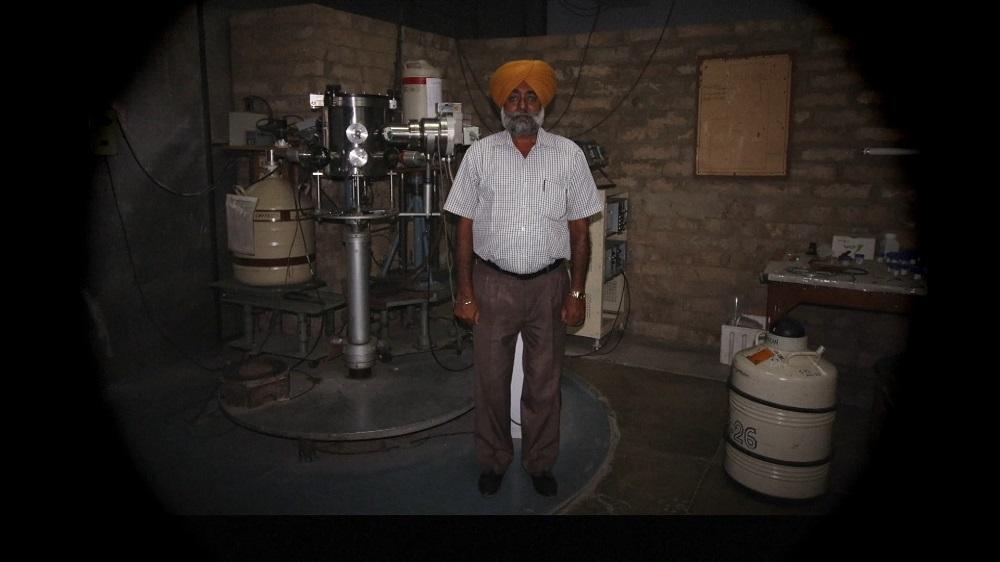

Handed down from the University of Rochester, the particle accelerator was lugged over to India by Harnam Singh Hans in 1967 and set up at his workplace, Kurukshetra University, in Chandigarh. The machine was the first particle accelerator in the country at the time and could be used by students of theoretical physics outside of Bombay and Calcutta. Being “second-hand” on arrival, however, it required intensive care and complex operations to merely set it up for laboratory work. A disparate cast of individuals—from PhD students to engineers and laboratory assistants—contributed towards making the accelerator run for regular research, against the odds of those who considered the machine to be a “white elephant”, a cumbersome remnant of an earlier age.

Phalkey traces the social conditions within which the cyclotron functioned in this unique location. She makes note of the close bonds created between workers, who were otherwise separated by a hierarchy of skills and knowledge. Keeping the machine running through breakdowns, producing a steady, high-energy beam (that could be directed towards analysing materials or disintegrating atoms to create novel isotopes for medicinal use) or simply waiting around for the elusive replacement accelerator that has been promised for years, created a nascent scientific community that remains invisible in popular accounts of scientific achievements. Tasks become inter-changeable as food and tea are shared during all-nighters at the laboratory. Caste and social hierarchies become unstable in the course of such participatory research—even though, in the end, the researchers recognise the limitations put upon them by their social and political contexts. By the time their work had begun attracting plaudits among the Indian scientific community, Punjab was beset by sectarian riots in the early 1980s. A new cyclotron, initially promised to this laboratory, was eventually sent to New Delhi instead. Towards the end of its tenure, Phalkey gently suggests that the machine has probably overtaken the research agenda rather than the other way around. Her film offers a machine’s-eye view of the community that was fostered around the cyclotron. It provides us with a narrative of the means by which the myths of scientific progress become the stuff of everyday practice and what gets lost in this process of translating these myths into postcolonial reality.

To read more about artistic responses to nuclear visions in India, revisit Najrin Islam’s essays on Himali Singh Soin’s static range and Moonis Ahmad Shah’s Gul-e-Curfew as well as Gulmehar Singh Dhillon’s reflection on Amirtharaj Stephen’s documentation of the protests against the Koodankulam Nuclear Power Plant.

All images from Cyclotron (2020) by Jahnavi Phalkey. Images courtesy of the director.