Afterlives and After-acts: A Reflection on Phototrope's Documentation

The first segment of this two-part essay dwelled upon the spatial and technological factors that mediate how an image is generated and made present. This segment focuses on Phototrope’s photographic documentation—a record-making considered crucial for the afterlife of an exhibit—and the agents that frame the readings of the work through its documentation.

My observations in this segment are drawn from the photographic documentation by lens-based artist Ajit Bhadoriya, present within the portfolio of Phototrope and shared by its artist Tahireh Lal. While there are many ways in which the works have been documented, my reading here stems from having noticed predominant patterns in the photographs that tend to expand the scope of documentation.

.jpg)

The layperson’s photographic documentation of an art project is often aimed at being a record for personal use or for making evident their presence and location. On the other hand, the professional documentation of a work is governed by other considerations: It corroborates the work as an exhibitory event, makes it accessible to a wider audience, represents the artistic practice, and becomes the primary access point through which the works are transacted, selected for projects, or submitted for grants. For Tahireh, documentation is more an after-act than an afterthought. It is a process undertaken not just after the exhibition’s execution but also at various stages of formulating the work and prior to the final display to lend a sense of the space and spectatorship for prospective galleries who might be interested in exhibiting such experiential works.

In a conversation centred on the act of documentation, Ajit shared how he aims to capture the likeness of form, material, texture, scale, space, spectatorship, and experience when documenting works for artists, galleries, and museums, with as little personal involvement and mediation possible.

Due to the exhibitory and experiential nature of Phototrope, outlined in the first segment of the essay, Ajit had myriad ways of experimenting with the composition of the images. The works allowed him to playfully intervene with and explore the forms, while rethinking the method, purpose, and scope of their documentation. His documentation of the body of work as photographs turned into a collaboration with Tahireh, leading to new experiences and readings not necessarily facilitated by the exhibition or even initially intended by the artist.

.jpg)

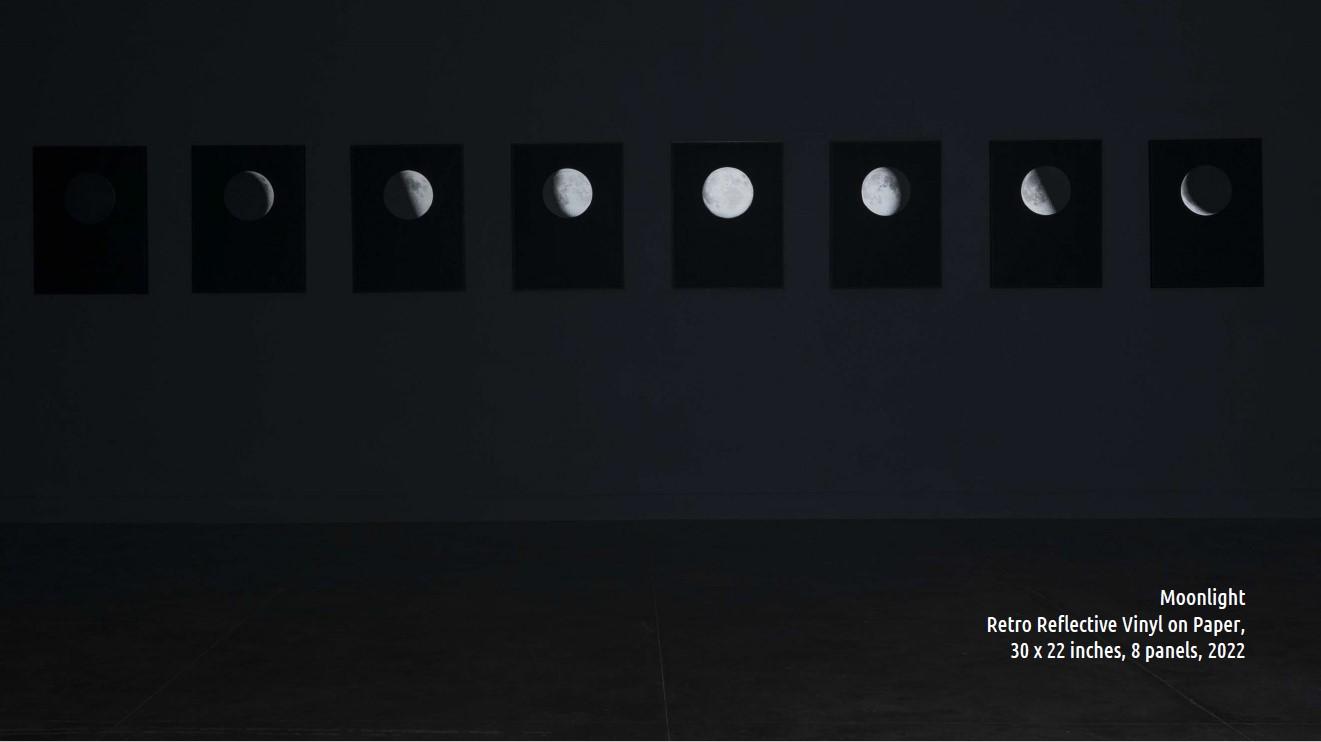

For instance, Moonlight—shot with uniform lighting—goes beyond the spatial instance of a fleeting presence and focuses on capturing the climactic moment when the image becomes fully present. Composed as a photo series, it condenses the spatio-temporal experience of the work in a single time-lapsed image. Here, the visibility of the image is foregrounded over how the image becomes perceptible, laid out in a specific linear order towards which the gaze is directed.

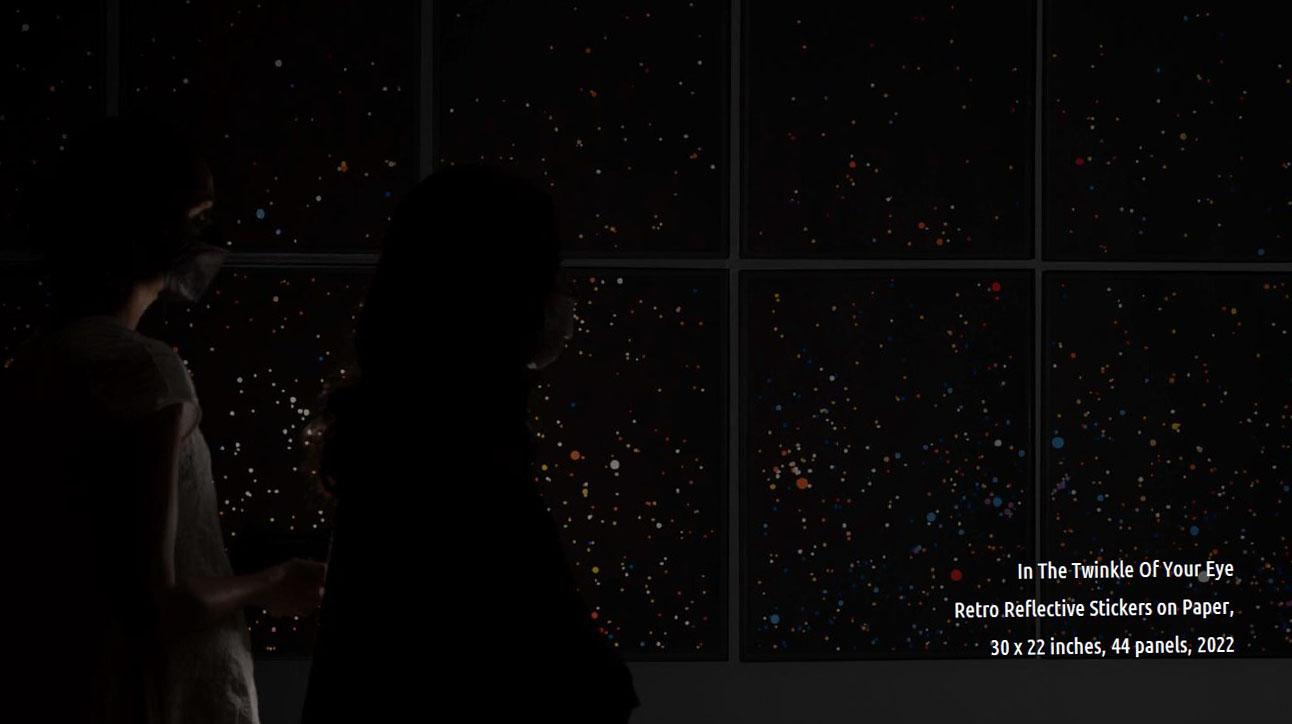

In Ajit’s documentation of In The Twinkle Of Your Eye, the form of the image was conceived in the moment of the shoot, where the silhouette of the viewer is contrasted before the work. Here, the viewer, who in the exhibition activates the work, comes across more as an onlooker, indirectly involved in the work, despite the presence of the torch in the frame. The grid-like arrangement of the panels appear as a sequence of video frames to be traversed spatially. Placed horizontally, it retains the experience of seeing a video in a dark, immersive room, and perhaps even signals a relation to Tahireh’s use of video as one of her preferred art forms.

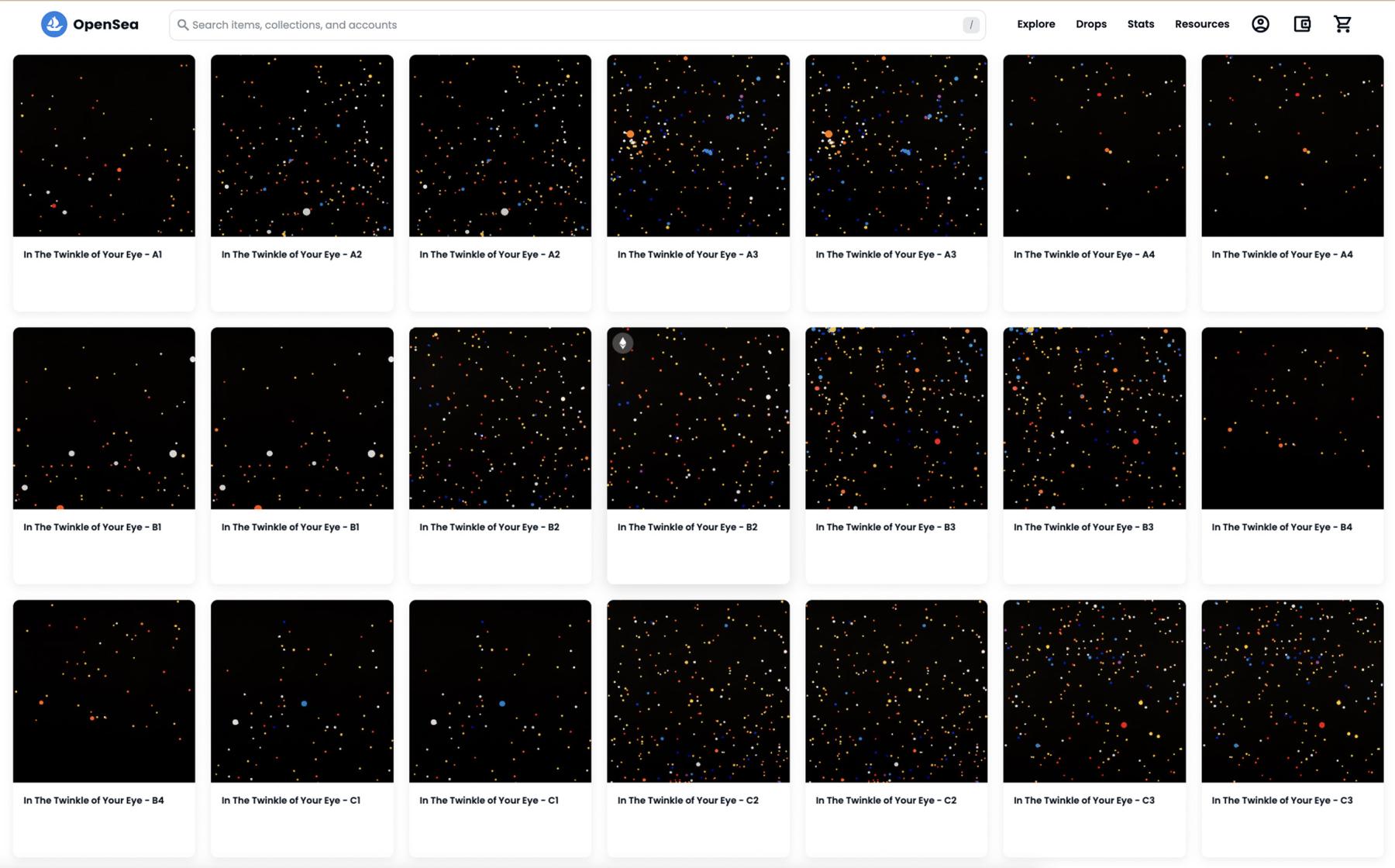

Alongside the photographer, the platform(s) used to circulate the work also frame its reading and comprehension with their interface, intended audience, and platform requirements to make the work compatible with various devices. In the exhibition note accompanying Phototrope, a QR code takes the viewer to the NFT platform OpenSea, which generates an iteration of In The Twinkle Of Your Eye. Since the maximum file size allowed by the platform is 100MB to reduce loading time, it impacts the resolution of the image, its size, and composition. Accounting for the above factors, the work’s transient quality is replaced by flat, almost solid and meticulously constructed works on paper on OpenSea. Presented in the form of a grid and filtered by lenses of purchase, quantity, and formats of view, the white space of the platform’s interface becomes a screen through which a very dark sky can be viewed, as if seeing samples of a larger space.

In The Twinkle Of Your Eye on OpenSea.

The use of the torchlight in Phototrope often simulates the quality of a firefly-like intermittence. However, as one continues to look at the works, the plasticity of the retroreflectors comes to the fore. At first glance, the moon’s glow is perceived as natural, only to reveal the technological, digital, and cultural mediations that form our reception of and relation to distant space and forms. While Phototrope’s actual experience leaves one with a string of afterimages, its documentation—a process that is often an afterthought with exhibits—offers a generative moment to re-frame the works. The documentation then goes beyond being supportive and secondary to becoming essential in ruminating how a work lives several lives to different ends.

All images courtesy the artist and Stuti Bhavsar.

To read the first part of this essay, click here. To read more about experimental image making, click here, here and here.