Cane Juice

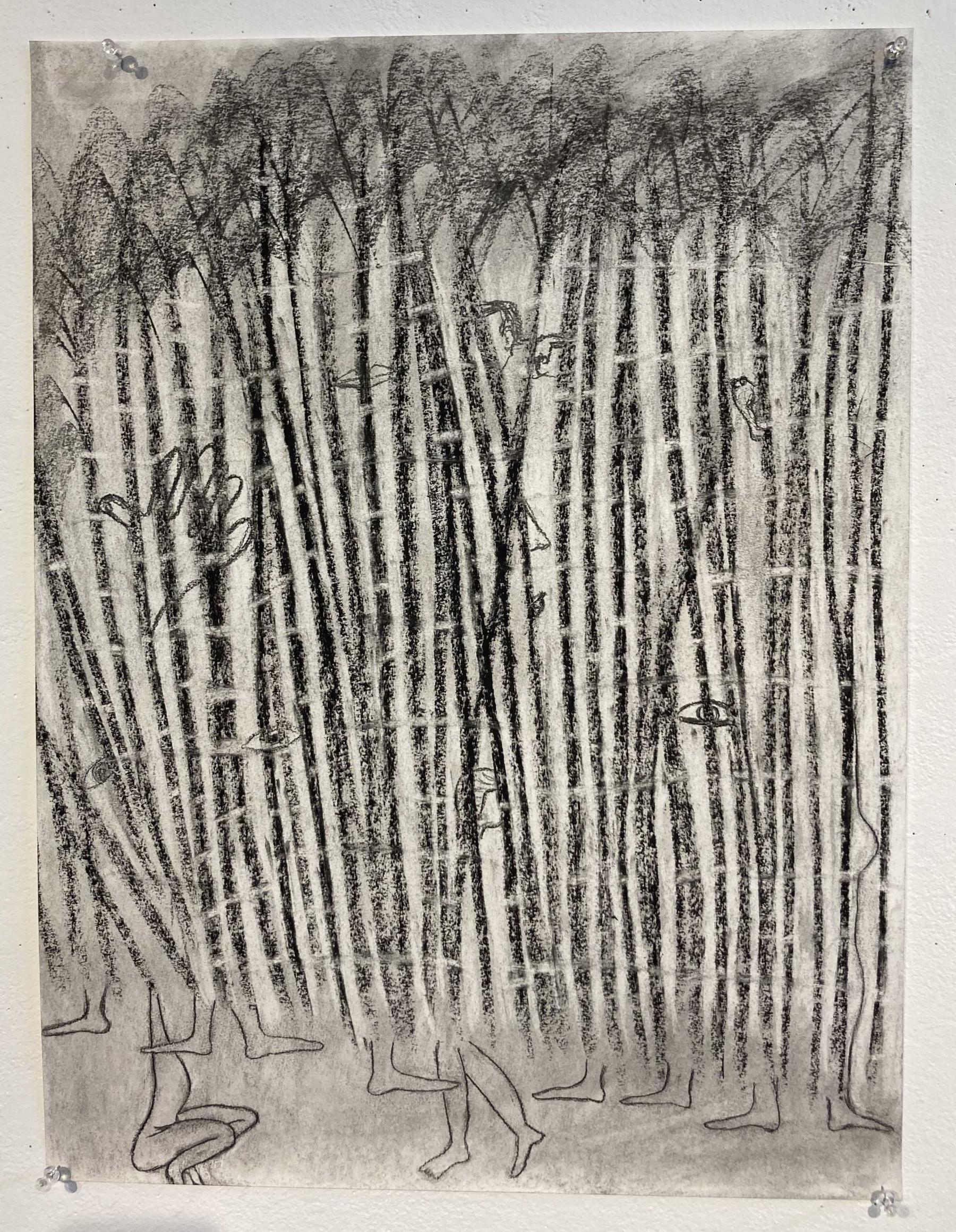

Gowthaman Ranganathan. Caned: Incomplete (2022). Charcoal on Paper, 18 x 24” inches. Courtesy of the writer.

He got down from the Mumbai Local, the local trains that connect Mumbai’s suburbs to the financial hub at Nariman Point where Muthu worked. His daily routine was fixed: leave from his small suburban house at 8 am, take the bus to the Mulund railway station, get on the 8:42 Mumbai Local to VT—once the Victoria Terminus renamed now to Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, and another bus ride to Nariman Point where he worked from 10 am to 5 pm as an office clerk. In the evening he would trace his way back to his house with a stop at the market at Mulund station to pick up vegetables. Today, he planned to stay longer at the market to meet a stranger he had connected with in a Yahoo chat room named ‘Mumbai Global 9’. He made his way through the crowded station and walked to Ganpat juice junction – a shop that crushed sugarcane and served fresh juice from morning to night.

As he got to the juice shop, he was welcomed by two big bundles of pale sugarcane stalks placed on either end of the entrance that acted as decoration and an invitation for customers. He took a seat at a table; the surface was sticky from juice spills, despite the constant cleaning by the staff who attended to patrons at the table. Muthu had to pick from the plain or lemon flavor of cane juice. He went with the classic plain flavor, no ice. As he waited for his glass, his ears tuned in with the rhythmic ringing of the bells tied to the cane crusher which jingled as the wheels went round and round. And his eyes were fixed at the stalk crushed through the ridged grinding surfaces again and again, folded each time to get the most out of them.

The juice will calm my nerves, he thought. He worried about the blackmails and assaults he had heard about. A recent attack had happened on a friend. At the park, a stranger had screamed at him ‘gud hai saala’ – ‘a fucking faggot’ and pushed him down. ‘Gud’—How did a lump of jaggery come to mean queerness? he wondered. Is it because of its sweetness? Or its raw unrefined state? Or because it can be crushed? Brushing his fears aside, he took the glass of juice. The first sip was refreshing, and he kept gulping. Then he paused, wanting to relish the drink and not rush through. The sweetness calmed him. He hadn’t realized how thirsty he was. The sip made him conscious of his body as the bells continued ringing in the background.

The cane stalks in the shop were pale, not like the black cane he was used to chewing. The dark one is tender and easy to chew, and the pale ones were harder, well suited for the cane crushers. His thoughts drifted to the Pongal celebrations in his hometown. A harvest festival to thank the sun god. A few days of rest and pampering for the cattle, plow, and the people. Along with his cousins, he would circle an earthen pot of boiling Pongal under cane stalks tied to create a frame as they chanted ‘Pongal o Pongal’, reaching a crescendo as the Pongal boiled over. The white and savory Pongal cooked with rice, lentils and peppercorn was special for Pongal, but the true treat was the Sakkara Pongal—the dark brown, gooey, rice cooked with jaggery and on good days with cashews, cardamom, raisins, and ghee. First offered to the gods of rain, sun, and earth and then served to people.

It was Pongal fifteen years ago when Muthu and Kumar were lazing near the dense cane fields, chewing on cane. They bit the edge of the cane stalk with their molars, getting a grip and ripping the dark bark to reveal the white fibrous juicy inside. When the bark has been removed around the stalk till the next node, they chewed off a chunk of cane relishing the juice. They chewed till all that was left was the bland fiber, spitting it out before the next bite. As they went about chewing the cane, Muthu felt the fatigue of the process in his mouth as his jaws throbbed from the effort. As the sun was setting, Muthu was stirred by the sweet fragrance of Gokul Santol, the sandalwood talcum that Kumar had dabbed on him. Intoxicated by cane juice and the talcum fragrance, Muthu held Kumar gently, acting on the desires he clung to himself at night as he laid next to the extinguished kerosene lamp. They met often until life took over and Muthu moved to Bombay, now Mumbai.

Since then, Muthu tied his desire into a tight knot and placed it in his chest. The knot would unravel in a cybercafé as he entered the Yahoo chatroom ‘Mumbai Global 9’ and saw ‘M2M?????’ appear at a rapid pace in different font sizes and colors. He made his way through the labyrinth of houses clustered haphazardly, creating lanes that did not rhyme. He emerged from the maze to the main road and walked past the Murugan Kovil, the temple of the Tamil god Murugan, and climbed the stairs of a building that housed establishments that had nothing to do with each other – a printing press, a lawyer’s office, hair salon, and at the end of the corridor – a cybercafé. He took a seat in one of the cabins with half doors labeled ‘Neptune’ – the other cabins followed similar planetary names. On the flickering computer screen, in a dingy room, his knot loosened and came undone as he joined men who were seeking other men.

He hurriedly typed chatwithme as his username. Taken. chat_with_me. Taken. chat_wid_me_123. Available. As chat_wid_me_123, he entered the room and was flooded by messages that popped all over his screen in small boxes. Perhaps the visitors were well-rehearsed with the regulars and were drawn to the new name. As he made his way through the crowded screen, one box caught his attention.

Sweet_talker1: asl?

And he replied.

Chat_wid_me_123: means?

Sweet_talker1: M2M? whr? age?

Chat_wid_me_123: Yes. Mulund. 33.

Sweet_talker1: tamil-a?

Chat_wid_me_123: aamam

Yes. And the joy of typing Tamil in English transcription took over. Tamizhukkum amudhendru per – Tamil is also known as nectar – a 1965 Tamil song from the movie Panchavarna Kili, a song Muthu had heard on the radio many times. And here was Sweet_talker1 saying things in Tamil typed in English, of things that Muthu didn’t know Tamil had words for—nectar indeed. His half an hour slot at the café was coming to an end. He did not want the meter to jump to the next half an hour, making it expensive. Sweet_talker1 and chat_with_me123 decided to meet at Ganpat juice junction, each with a white handkerchief folded and placed in his chest pocket.

At the juice shop, Muthu was beginning to worry. Sweet_talker1 had not arrived, he had finished two glasses of juice and he could feel the impatient look from the shopkeeper. He ordered for a third glass to buy time. Too much sugar is never good. He felt the bitterness of the third glass. Worry returned. He has yet to buy vegetables. Meera would be waiting for him and worrying too. He would have to help Suresh with homework. The knot in his chest tightened. As soon as the third glass of juice was done, he’d leave. His gaze was fixed, but he was looking at nothing in particular. The shop buzzed at its rhythm like files moving from one desk to another in his office.

Someone approaching the table pressed on his awareness. Maybe there was a whiff of Gokul Santol talcum…. He placed the glass on the table and looked up to face his fear, his desire, his past, and perhaps his future.

Photographs of the neighbourhood in Mulund, Mumbai. Courtesy of the writer.

Gowthaman Ranganathan is a Ph.D. student at Brandeis University’s anthropology department. Cane Juice was written for a class on ‘Sugar – Cultivation, Circulation, Power’ co-taught by Professor Elizabeth Ferry and Professor Gregory Childs at Brandeis University.