Decolonizing German Television: The Fifth Wall and the Media Legacy of Navina Sundaram

Earlier this year, the Sher-Gil Sundaram Arts Foundation (SSAF) organised a panel discussion on The Fifth Wall, a digital archive of the television programmes and documentary films by Navina Sundaram. Moderated by Madhusree Dutta, the panel included Merle Kröger, Deepa Dhanraj, Sashi Kumar and Volker Pantenburg as speakers. The discussion was organized a few days after select films from the archive were made publicly available online. The archive, created by Kröger and Mareike Bernien, brings together films, television programmes, letters, texts, reports, photographs and annotations made by Sundaram or those pertaining to her work in Germany.

Prior to co-founding the SSAF, Sundaram worked for the German public television for about forty years. She spent most of her time working with North German Broadcasting (Norddeutscher Rundfunk/NDR), covering many pivotal historical events from the late-1960s; the range and subject matter of the films are disparate, even for the tumultuous late-Cold War period. However, what stands out in Sundaram’s work is its radical and subversive potential for re-thinking a media history of the globalising world, as it tried to infuse the politics of the newly decolonizing world—from South Asia to South America—with the insular frames of German television. These videos reflect the decades of life in a divided and eventful Germany, equally invested in events such as the Indian Emergency, the liberation of Bangladesh, socialist struggles in South America or granular biographical portraits of subversive political actors like Amilcar Cabral or George Fernandes. However, as some panellists in the symposium argued, the utopic notion that Sundaram’s work has left an indelible legacy of decolonial thought on German television is debatable—considering the strong Eurocentrism and the more extreme variant of racially white German nationalism rampant in the country’s media landscape to this day. Sundaram’s work has been associated with other critical media practitioners such as Harun Farocki, which suggests a genealogy of the media as a historically and materially graspable object of inquiry in Germany.

Nevertheless, Sundaram’s work was not just limited to bringing reportage from around the world to Germany but, as the archive hopes to illustrate, it also highlighted how the media presented those events was instrumental to driving global political change.

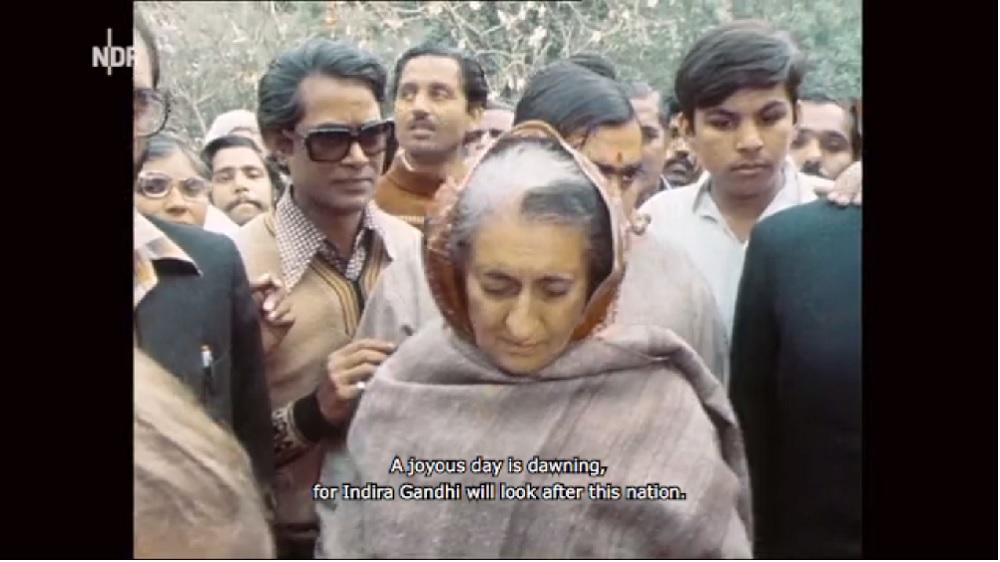

Sundaram, seen here with George Fernandes, confronted political leaders with a kind of frankness that was usually denied to state news agencies that had a monopoly on television news media in India before the 1990s.

While elections remained the most obvious occasion for on-ground reporting from India, Sundaram attempted to reflect the moods of both the citizenry and the world at large in relation to the subject of South Asian democracies in practice.

Predictably, some of the correspondence includes abusive racial threats directed towards Sundaram, which is testament to the conditions in which she ploughed a somewhat lonely furrow. Her curious presence around leaders and people on the streets of Delhi or Dhaka, seen in this archive, is clear evidence of how critical her contribution to critical media has been. The archive reflects Sundaram’s knowledge of the intricate details that shaped “local” politics in the global South, largely invisible from the narratives of the region and explicable from the logic of the Cold War. By operating outside the media apparatus of India, Sundaram could also engage in a critical intimacy with her subjects that Indian journalists could not always afford. She maintained her political commitment to the voiceless by resorting not just to criticism but also irony and sarcasm, often directed against the personality cults set up by leaders like Indira Gandhi or Mujibur Rahman.

The speakers at the symposium highlighted the multiple possibilities of Sundaram’s archive and its implications in understanding media histories. Madhusree Dutta highlighted the archive’s demonstrated potential for writing “multi-locational” histories of the world, and she also emphasised the need for increased accessibility and curatorial projects to orient it in meaningful ways for the public.

Sashi Kumar compared the ethics of media archaeology with the ideologically manipulative contexts constructed by the Indian media. Kumar argued that as long as media archives function as representations of state memory, egalitarian modes of access will remain unthinkable; although, other panellists did point out the critical role that state archives have played in works such as the 1992 film Videogramme einer Revolution (Videograms of a Revolution) by Harun Farocki and Andrei Ujică. Nevertheless, this line of inquiry provoked questions around the nature of the archive itself: is it simply a collection of loose materials or can it be seen as fragments of a narrative?

Sundaram’s vantage point in Europe allowed her to obtain a larger view of decolonisation across the world, as a process linked inextricably with the trajectory of other postcolonial nation states as well as their former colonising states, looking to create spheres of influence in politics and culture.

Volker Pantenburg attested to the aesthetic claims of the archive as well, arguing that its value cannot be ascertained in economic terms alone. He lauded the curatorial possibilities and critical framing of the archive, which allows researchers to better comprehend the sheer range of German mediascapes. For Pantenburg, The Fifth Wall paves a way for future archives of media histories.

Deepa Dhanraj and Madhusree Dutta spoke about knowing Sundaram during her working days. Dhanraj pointed out that a lot of Sundaram’s work was enabled by the excellent access to a wide variety of subjects that German television granted her, something that independent documentary filmmakers like Dhanraj have almost never had. However, for Dhanraj, Sundaram’s streak of creativity is best reflected in her reports from unfamiliar regions, as she unpacked complex political machinations for a German audience back home.

Finally, Sundaram herself appeared briefly at the end of the discussion and outlined some of the necessary struggles she had to undertake to produce her work for television and documentary film, offering her enthralled listeners and friends an opportunity to hear from the one who many have dubbed the “the voice of the South”.

Sundaram’s specialist focus may have been South Asian elections and politics, but she attempted to contextualise them against the background of world events, showing that even “non-aligned” countries could contribute to ideas of world making.

To read more about critical media practices in South Asia, click here, here and here.

All images from The Fifth Wall (2022) by Merle Kröger and Mareike Bernien. Images courtesy of Navina Sundaram, Merle Kröger, Mareike Bernien and the Sher-Gil Sundaram Arts Foundation.