Bigamy, Scandal and the Homewrecker Film: Bollywood in the 1980s

In 1980, Filmfare stressed on one of the stories doing the rounds about the coming together of actors Amitabh Bachchan, Jaya and Rekha in Silsila (1981): “Jaya told Amit, ‘If the film flops, I’ll leave you, and if it’s a hit, you should leave Rekha.’” To give context to this piece of gossip, a year later, when the much-touted film’s shooting began, Yash Chopra, its director, “denied that he had conveniently seized upon this theme in order to capitalize on all that gossip and speculation about Amitabh, Jaya and Rekha in real life.” He went on to say that the film’s theme was “extra-marital relationships,” but its goal was to uphold “the sanctity of marriage.” It was a hugely successful film, whose overseas video sales to the United States of America and Canada were at a record high, and the echoes of the reel and real scandal and infidelity travelled far enough to bring in letters from fans in Mombasa (Nazir Bachani wrote one such letter to Filmfare in 1982, titled “Victimized Film?”). Silsila had strategically nipped any possibilities of bigamy or divorce in the bud.

The tragedy of the Rekha-Amitabh affair, Filmfare, May 1-15, 1981, 12.

Shooting stills, Souten (Sawaan Kumar Tak, 1983), Filmfare, November 16-30, 1982, 48.

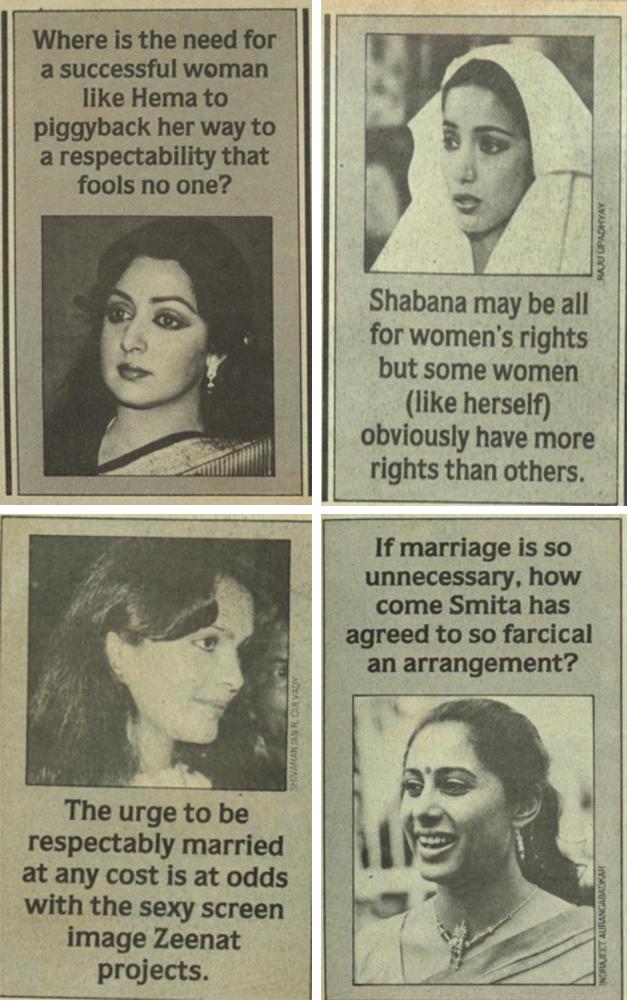

A few years later, three leading Bollywood actresses—Zeenat Aman, Shabana Azmi and Smita Patil—had broken the taboo of marrying already married men (Aman, twice, despite the calamitous public assault she faced at the hands of her first, married husband, Sanjay Khan). Some magazines and tabloids quipped that these actresses and their bigamous partners— Mazhar Khan, Javed Akhtar and Raj Babbar respectively—followed the footsteps of actor Dharmendra who had converted to Islam in 1979 to marry Hema Malini. After the helter-skelter wedding, Malini lived separately with her two children while her husband lived with his first wife and their adult sons. In the 1980s, marriage was clearly a money-spinning excess both on-screen and off-screen. Big-budget films themed around infidelity, such as Souten (Saawan Kumar Tak, 1983) and Silsila were filmed abroad, in Mauritius and The Netherlands respectively, and expanded the overseas market of Indian films. Medium-to-low-budget, mass-produced films such as Ek Hi Bhool (T.R. Rao, 1981), Doosri Dulhan (Lekh Tandon, 1983), Nazrana (Ravi Tandon, 1987) and Aakhir Kyon? (J. Om Prakash, 1985) starred actresses known for marrying their already married lovers. “Social issue films,” like Arth (Mahesh Bhatt, 1982) and Yeh Nazdeekiyan (Vinod Pande, 1982)—starring Parveen Babi as the “homewrecker”—referenced Babi’s own affair with Bhatt, allegedly dovetailing her mental illness with guilt and shame, leading to the actress exiting the film industry.

Sherna Ganghy, “Whose Wife Is She Anyway?” Filmfare, August 16-31, 1985, 52-57.

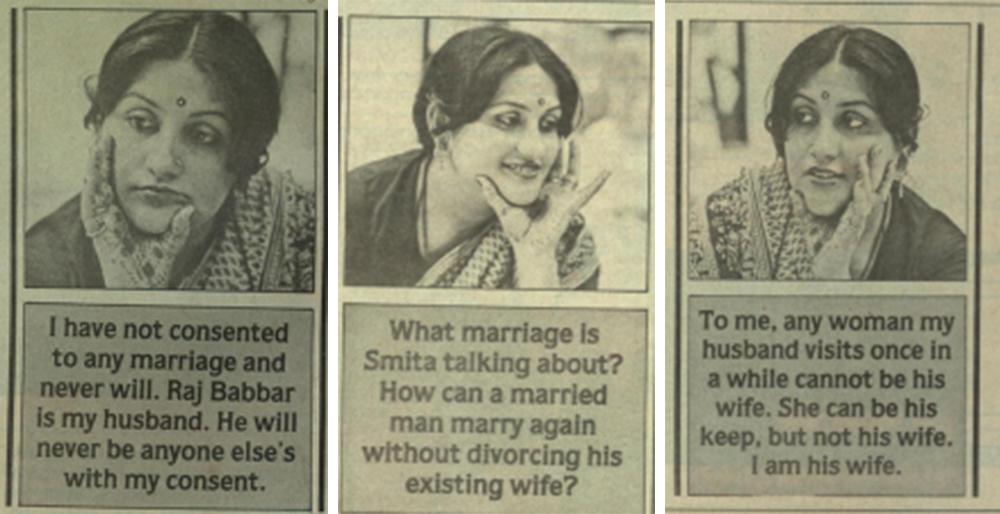

The film industry was in a state of flux, financed by new players including diamond merchants and those from the underworld. New talents like the all-baring, extremely young, “starlings,” as well as the new morality ushered in by the quiet bigamy of successful male film personalities with actresses known to be outspoken champions of women’s rights, was met with panic, scorn and suspicion. Reports in film magazines voiced the continuous anxiety of what might become of “our film culture” if homewrecking and bigamy were normalised, and thus made respectable. Filmfare became obsessed with the anxieties about what the evil of open marriages would do to warp the Bombay film industry and its future generations, most of which tended to emphasise imaginary possibilities rather than realities. Open letters by Nadira Zaheer Babbar—Raj Babbar’s first and legitimate wife—published in Filmfare in October 1985, and by Vimla Patil, the editor of Femina condemning Smita Patil for breaking up Babbar’s marriage, presented that possibility in bold, new ways.

Nadira Zaheer Babbar, “’My silence doesn’t mean consent’” Filmfare, October 1-15, 1985, 8-15.

Rekha, the most celebrated “other woman,” never stood a chance of following suit most immediately, as Bachchan had begun his political career in 1982. A politician couldn’t afford to be promiscuous, at least publicly. Rekha’s public scandals (being slapped by Bachchan), her romance, her passionate outbursts during interviews, such as the one with Mahesh Bhatt published in The Illustrated Weekly of India and reprinted in Filmfare in 1985: “I feel so complete in this relationship…One second with this person is like getting pregnant and carrying his baby,” supplied the glitter and grime for the homewrecker films, keeping the film industry and its extension—the film press—afloat at a time when it was going through a recession.

.png)

Sherna Ganghy, “Whose Wife Is She Anyway?” Filmfare, August 16-31, 1985, 52-57.

.png)

The “Homewrecker films” reported in Flashes, Filmfare, May 16-31, 1981, 63.

All images courtesy of the National Film Archive of India.