Projecting the Gaze: A Conversation with Sibi Sekar

While Sibi Sekar’s short experimental feature You Are, I Am has been previously discussed, the filmmaker also spoke to Ankan Kazi about some of the influences underlying his work of developing a critical cinematic gaze to refuse the normative framework of the visual pleasure in looking. From experimental feminist filmmakers, such as Barbara Hammer, to the intriguing notion of (non)film—signifying a search for essential cinematic forms which can be stripped of their determinative cultural habits—Sekar’s responses trace a map of the networks connecting South Asian experimental films and video works to traditions of experimental practice developed in Europe and America, over the last few decades.

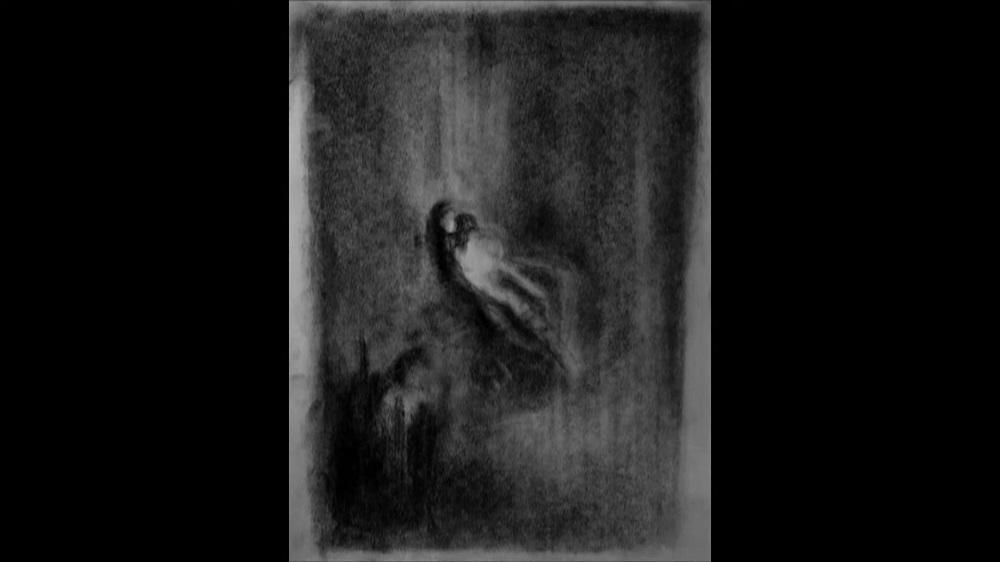

Still from Sibi Sekar's You Are, I am. Courtesy of Sibi Sekar.

Ankan Kazi (AK): Barbara Hammer’s I Was / I Am (1973) appears to be directly referenced in the title of your film. How do you see Hammer’s films informing your own work?

Sibi Sekar (SS): As a film enthusiast myself, I discovered the pre-existing truth that the majority of viewership deeply indulges in the mainstream cinematic gaze that is almost always organised around a patriarchal, binaristic gaze... Experimental or avant-garde films were and are the only gateway to exploring (non)conceptualised ideas due to their engagement with abstractions and ambiguities. I arrived at this conclusion through the revelatory experiences I've had interacting with the films made by Barbara Hammer, Carolee Schneemann and Hannah Wilke, to name a few.

In 1975, British feminist film theorist, Laura Mulvey articulated the concept of male gaze. She stated that the vast majority of films were governed by the male norm and effortlessly objectified the body of women. Barbara Hammer, around the same time, broke the prevailing rule by making short moving image works in which she naturally adopted an antithesis to the male gaze. The female gaze in cinema is a conceptual way of filming that attempt to restore the experience of female(s) and femininity in its purest subjectivity.

The films of Barbara Hammer can best be described as a world of unexplored sensations, rediscovered and represented—intimate experiences presented, represented, deconstructed and reconstructed. As Hammer noted, “There is not a feminism, but feminisms, not a lesbian cinema but lesbian cinemas, and there is not abstraction but multiple manifestations of abstraction. My films portray worlds populated by lesbian, queer and gender diverse subjects, erotic, comfortable and changing bodies.”

Barbara Hammer (left). Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

AK: Aside from their often conscious appropriation of a specific, critical genealogy for themselves (Hammer’s film was made as a tribute to a generational figure in feminist experimental cinema before her time: Maya Deren), what are the forms or concepts that attract you to Hammer’s films/videos?

SS: I admire the films of Barbara Hammer, but I admire her as an individual a lot more, especially for her tenacity. She made the impossible possible, she turned the then “yet-to-be conceptualised idea(s)” such as the female gaze, into a definitive concept that is now widely accepted by the world. In fact, it goes beyond acceptance and today, the female gaze in the art world is more of a lifestyle choice to many.

In my film(s), all I try to capture are these yet-to-be conceptualised idea(s). To be more precise, non-existent ideas such as (non)film and (non)gaze or (anti)gaze are of deep interest to me. (Non)film, as I understand it, and in simple words, is a film that situates itself outside the definitive characteristic traits that have been historically and culturally attributed to films. Similarly, (non)gaze or (anti)gaze is a way of seeing or perceiving object(s) from a standpoint not previously defined or pinpointed. It goes beyond the binaries and then a little further ahead, where true and ultimate deconstruction occurs.

Still from Sibi Sekar's You Are, I am. Courtesy of Sibi Sekar.

AK: There is a conscious adoption of ambiguity in your film, where a viewer’s gender(ed) expectations are made uncertain, leading to a kind of anxiety and even revelation that is not familiar to the audience of a pleasing, commercial film. Is there a relationship that you’re trying to build between the abstraction of form and the question of gender identity that is constructed by the gaze of a film?

SS: Mainstream cinema, for obvious reasons, doesn’t allow for such explorations. Whereas, due to the extremely unpredictable style of avant-garde and experimental films, innumerable revelations are made possible. The depth one can achieve through abstractions, which is the primary approach of experimental cinema, is seldom the subject matter of the works of film theorists.

(Non)conceptualised ideas can only be dealt with in terms of abstractions, and the deeper the engagement with abstractions, newer ideas can germinate. These ideas are further explored and critiqued until they become a definitive concept/theory. This process of conceptualising or realising (non)existing ideas and normalising ones that are considered taboo is highly prevalent in avant-garde and experimental films.

This process intrigued me, and I also felt naturally inclined to express these abstract ideas through abstract imagery. Since you mentioned ambiguity in your question, I would like to add that most of my films usually portray an abstract world populated by ambiguous identities. I tend to call them non-entities/projections, and they act as catalysts for the ideas I try to convey. It is an approach that helps me free myself from social constructs or, to be precise, free myself from the preconceived ideas already explored through gender and identity constructs.