Bearing Witness: On Prashant Panjiar’s Exhibition That Which is Unseen

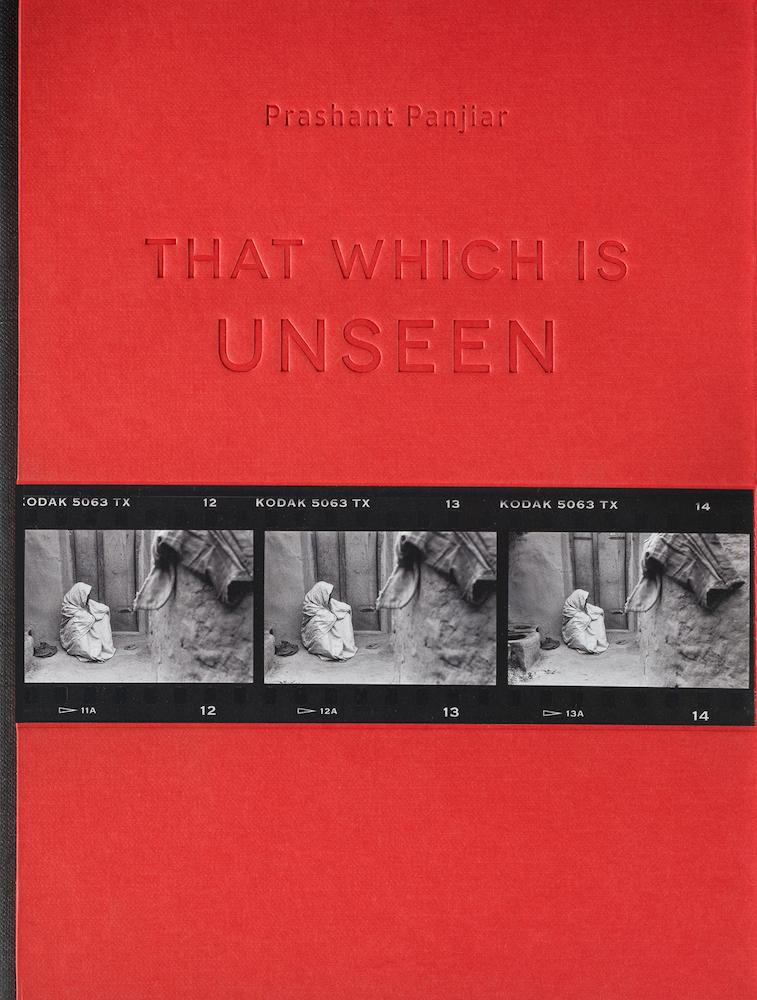

Cover of That Which is Unseen by Prashant Panjiar. Published by Navajivan Trust, Ahmedabad, 2021

A selection of photographs from Prashant Panjiar’s latest book That Which is Unseen was presented as a solo exhibition at Museo Camera Centre for the Photographic Arts, Gurgaon in March 2022. Published in September 2021 by Navajivan Trust, the book is a compilation of over a hundred photographs, accompanied by Panjiar’s personal stories about them from over three decades of his work as a photojournalist. The exhibition consisted of thirty-two such photographs from the book, curated chronologically along with their backstories. Panjiar is a veteran photojournalist who has taken some of the most crucial photographs engraved in Indian public memory. The social context provides a characteristic anchor for the body of work—both in the case of the book and the exhibition.

Ek Aur Dhakka Do. (Prashant Panjiar. Ayodhya. 6 December, 1992. India Today / That Which is Unseen.)

Some of Panjiar’s defining photographs include those of the demolition of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya by the kar sevaks of the right-wing Vishwa Hindu Parishad and allied organisations on 6 December 1992, which have thereafter been circulated under different circumstances and with varying agendas. Through Panjiar’s narration of the event, we realise why these were the only images taken of the Babri Masjid domes collapsing while being destroyed. Many of the other photographers and television crews on the platform in the front of the Babri Masjid had been systematically attacked and confined by the Hindutva mob to prevent any recording of the attack on the mosque. Panjiar, who was atop the terrace of a structure called Ram Katha Kunj, was assumed to be part of the mob and was hence able to photograph with impunity.

While individual memory can, at times, be unreliable—in this case, that of the image-maker—it can also act as a powerful tool against collective amnesia, or the citizens’ disposition to forget key moments in a nation’s history. Panjiar’s photographs are testimony to the importance of bearing witness as a photographer before the digital camera, the accessibility of digital visual media, the art of modification, and contemporary global media circulation radically changed our relationship with the evidentiary image.

What made these photographs a crucial part of public memory is that they bore witness and were printed in some of the most widely circulated weekly news magazines such as India Today and Outlook, where Panjiar worked, as evidence of the state of events in the country. Taken outside of their context of newspaper and magazine articles, the photographs face a risk of being reduced to a composition of visual elements. This is again where Panjiar’s personal narrative emerges as a conscious intervention—an acknowledgement of how photographs derive meaning and a decision to illustrate the photographer’s role as an observer who, despite maintaining journalistic ethics, is a political being.

Summertime: Liberalisation with no Safety Net. (Prashant Panjiar. Vidarbha. 2010. India Today / That Which is Unseen.)

For over three decades, Panjiar’s photographs have documented social issues which were precursors to the current state of the country—whether it is the violent persecution of minorities or the increasing farmer suicides since the 1970s. Since 1995, almost three lakh farmers have killed themselves across the country as a consequence of neo-liberal reforms, reducing the ambit of formal bank credit and leaving them at the mercy of market forces. Panjiar’s photographs then come across as a memorialisation of an India that existed in these three decades, where the economic liberalisation of 1991 looms in the background as a marker of irreversible change. Panjiar has relentlessly documented the rising communal violence during this period, but the series of photographs at the exhibition ends with one portraying the death of a farmer. Captioned “Liberalisation with no safety net,” this photograph from 2010 of a farmer who killed himself in Vidarbha points directly towards the country that is constructed through these photographs. One could also begin viewing the exhibition from this photograph, and journey through decisive photographs of a republic to photographs of descendants of maharajas of India who slipped into decay and darkness. What remains at the end of it is still a bygone republic which has slipped further into majoritarian rule.

Newborns: The Dais (midwives) (Prashant Panjiar. 1995. Outlook / That Which is Unseen.)

Panjiar’s extensive body of work remains crucial because of a certain truth value and belief that was ascribed to photojournalism of that era. However, it also forces us to acknowledge that it is impossible to make photographs in the same manner today, especially within reportage, not only because of how they are circulated but also because we are all bearing witness now through a constant documenting of every event through our phones. This does not negate the necessity of photojournalists and the work they still do, but allows us to reconsider the role of the photographic image which seeks to grant subjecthood to the oppressed. Can the role of the documentary image instead become the means to counter the collective amnesia of a people? In the face of attempts at rewriting history and a constant influx of information through our digital networks, how can historical photographs persist as important cultural data that resist an erasure of memory?

An installation view of That Which is Unseen at Museo Camera Centre for the Photographic Arts, Gurugram, March 2022.

All images courtesy of the artist.

To read more about the collateral events at the India Art Fair 2022, please click here.