Quarter Number 4/11: Looking Back Ten Years On

On 24 December 2008, ex-factory worker Shambhu Prasad Singh’s quarter inside the Usha factory in south Kolkata was illegally demolished in the dead of night, leaving him and his brother’s family homeless in the city. Jay Engineering Works (JEW)—which began operations in the 1950s and were manufacturers of the iconic line of Usha sewing machines and fans—had sold off its factory on Prince Anwar Shah Road to make way for the “largest mixed-use property development” project, South City. The project, once complete, would comprise a residential complex with three 35-storeyed and one 28-storeyed tower, a school and a shopping mall, among other facilities. Demanding fair compensation, Singh and his family had waged a one-sided legal battle against his employers, refusing to vacate their home while the industrial landscape—in West Bengal and in their immediate vicinity—changed dramatically and beyond recognition. Their quarter, 4/11, was the last physical marker of the factory, the closure of which would imply 7000 people losing their livelihoods.

Quarter number 4/11 inside the Usha factory in south Kolkata.

An advertisement for South City, a mixed-use property development project.

Filmmaker and activist Ranu Ghosh had met Singh quite by chance two years prior to the demolition of quarter 4/11. As a part of her research under the Sarai CSDS Fellowship on Change of Industrial Landscape in Kolkata: Jay Engineering Works, Ghosh was studying patterns of real estate development in the city. News of the sale of the Usha factory land had alerted her to the plight of workers who had been forced to accept nominal sums under the Voluntary Retirement Scheme (VRS) and vacate their homes. Singh, whose father had also worked for the same company, had spent forty-five years of his life at Usha’s factories and had been a permanent employee himself since 1993—the same year that he was given his quarter. His fight for justice became the subject of Ghosh’s Quarter Number 4/11 (2012), whose making called for a remarkable collaboration between filmmaker and protagonist.

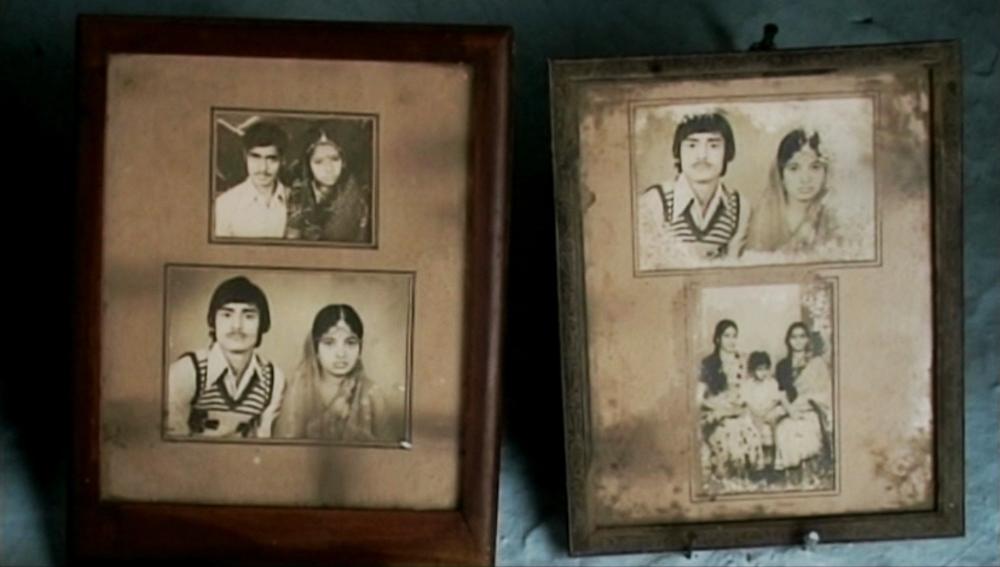

Photographs in Shambhu Singh’s ancestral home.

Shambhu Singh with his parents in their ancestral home in Gaya district, Bihar.

The documentary begins with a fairly predictable series of interviews: some are with property owners in the vicinity of South City who speak of the inconveniences caused by the construction process as well as its environmental impact. Others are with workers at the Usha factory who express their anger not just at their employers but also at the union leaders who had seemingly failed them. (An article from 2010 on Jyoti Basu by Siddharth Sriram of JEW in the Business Standard seems to suggest that the unions had signed a “historic document” agreeing to the plan of closing down the factory.) Shortly after Singh is introduced—he is seen fiddling with a handheld spring-toy as he somewhat proudly tells an interviewee about his solitary presence inside the building compound—Ghosh’s title card reveals her methodology that emerges out of a restriction: “I was not allowed to enter the construction site with my camera. I gave Shambhu a small handycam and a bit of training. He started to shoot.”

From that point the film takes the form of a dialogue, narrating the story using two different perspectives, marked by different kinds of access. While Singh documents the daily domestic struggles of his family as they contend with hostile surroundings, Ghosh’s visuals offer a broader context, subtly but powerfully drawing attention to the silence around the decline of industry and the rise of consumerism and gentrification in and around Kolkata. The sections shot on Singh’s handycam—recongisable from its typically limited dynamic range and high contrast visuals—also record his learning curve, as he directs his family members and composes the shots to pack in significant detail. For instance, in one sequence he asks his sister-in-law to make sure that the Usha label on her sewing machine is visible on camera, so it adds a layer of interpretive possibility to the narrative. By including Singh’s process of learning to use the handycam, therefore, Ghosh makes their methodology—and indeed the creative process of the film—a part of the documentary’s narrative.

An indoor scene shot by Shambhu Singh.

It has been close to ten years since Quarter Number 4/11 released, and a few more since the living quarter was illegally demolished. During a recent conversation, Ghosh told me that she is in touch with Singh’s family, who are still waiting for justice. After his death on 14 January 2011 caused by a hit-and-run incident on a highway, Shambhu’s son, Aryan, continued with his education and has recently completed his graduation. The film remains as a witness to Singh’s struggle, and to the network of solidarity that tried to support his cause at the time, which included Ghosh herself. In addition to documenting just one of many instances that laid bare the process of de-industrialisation in West Bengal post liberalisation, Quarter Number 4/11 remains a rare intervention in narratives of urban change and nostalgia, speaking as it does of nostalgia for a lived space from the perspective of an individual who experienced the city as a labourer.

Quarter number 4/11 being demolished.

All images from Quarter Number 4/11 by Ranu Ghosh. India, 2012. Images courtesy of the director.