Nodes of Listening: Reflections on “Artist Encounters” at Colomboscope

The milieu of interaction fostered by the “Artist Encounters” series speaks profoundly of the kinds of acts—of transmission, experimentation, narration—being helmed by the seventh edition of Colomboscope, Language is Migrant. The curated set of sharing sessions between artists brought together diverse questions of media, form and function across interdisciplinary practices, speaking to manifestations of geographies, socialities and the radical fluidity of language. Intrigued by the juxtapositions offered by this series of encounters, I chose to reflect on the modes of listening platformed by the third set of interactions. With presentations by Omar Kasmani, Iffath Neetha Uthumalebbe, Imaad Majeed, Abdul Halik Azeez and Hania Luthufi, the third episode of “Artist Encounters” framed acts of listening across Sufi symbolism and Islamic histories, sonic experiments, readings of architecture and place, and family photographs, creating intersections between different archives and methodologies.

A screengrab from Omar Kasmani’s presentation showcasing his work, Audible Spectres.

Omar Kasmani shared three interrelated sound recordings from two Sufi shrines in Sehwan, a renowned pilgrimage site on the banks of the Indus in Pakistan as part of his work, Audible Spectres. The recordings were excerpted from his extensive documentation at the shrines of Bodlo and Lal Shahbaz Qalandar as examples of how visitors to the shrine occupy a performative space. In offering devotion through music and sound, they create affective geographies through a public siting of their intimate connection with the saints. Foregrounding his interest in people’s relationships with sacred spaces, particularly the manner in which the devotional interacts with the non-devotional, Kasmani drew attention to the palimpsestic nature of such sites—in one instance, characterised by an overlapping Shaivite legacy. He spoke of his method of developing non-normative ways of reading the figures of saints as companions to their devotees, painting them as lovers and more-than-living entities, and thus queering a negotiation of sacredness in the present. Asking how histories survive despite the state, Kasmani reiterated the complexities of such sites, referencing their Shia history in a majority Sunni country and resisting governing attempts to “straighten” the site.

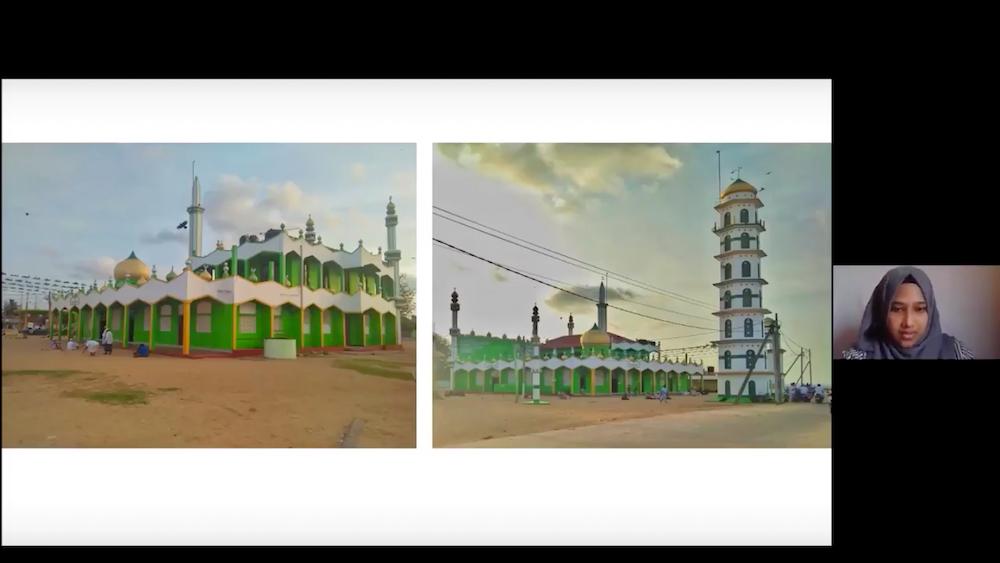

Iffath Neetha Uthumalebbe presented her study of mosque architecture in Eastern Sri Lanka, an undertaking to bring mosque architecture into the wider story of Sri Lankan artistic heritage.

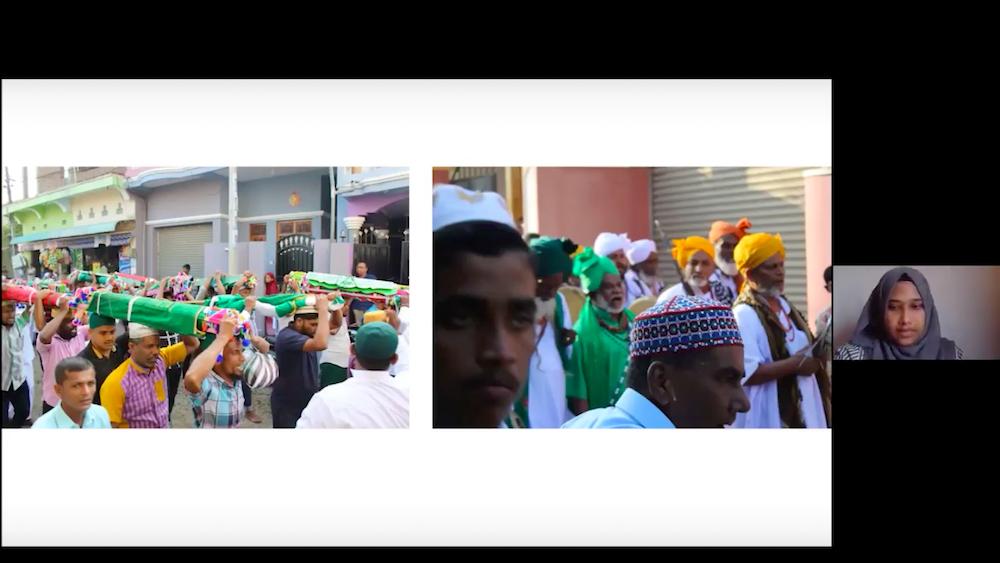

Iffath Neetha Uthumalebbe spoke of her work in Eastern Sri Lanka, looking at ways of studying mosque architecture and the linkages produced between tradition and vernacular histories. She addressed concerns of preserving Sufi cultural practices and traditional aesthetic forms in an abrasive present, sharing her efforts to collect photographs and oral histories as a way of intervening in the heritage of Muslim communities in Sri Lanka. Exploring solidarity in the region through inter-referential devotional aesthetics in flag-making traditions and architecture in Sainthamaruthu, Kattankudy, Oluvil, Eravur and Akkarapattu; Uthumalebbe highlighted interconnections between trade, craft, devotion, and coloniality prevalent in the vestiges today.

Uthumalebbe’s practice includes a focus on flag-making traditions, and she shared her personal interest in studying elements and processes that constitute these traditions, from the timber used to hoist the flag to the ways in which communities engage in the preservation of such nuanced inheritances.

Imaad Majeed shared his preliminary research on archiving Sufi and folk music from the island, undertaken through audio recordings—some found and some documented on site. Majeed’s project is an attempt to “collect” the sound of a vanishing culture, and he spoke of how Sufism in Sri Lanka has come to be viewed as an un-Islamic practice, facing immense pressure from proselytising movements such as the Tablighi Jaamat. Working with his collected sound material, Majeed has been melding vocals, melodies and percussion to create pieces with organic textures. The artist focuses on ambiences and experiences, representing vastly different Sufi orders and sites on the island. Incorporated into the tracks, they harbour a sense of dislocation, prolonged by their spectral sound—something he believes is a return to their sacrality.

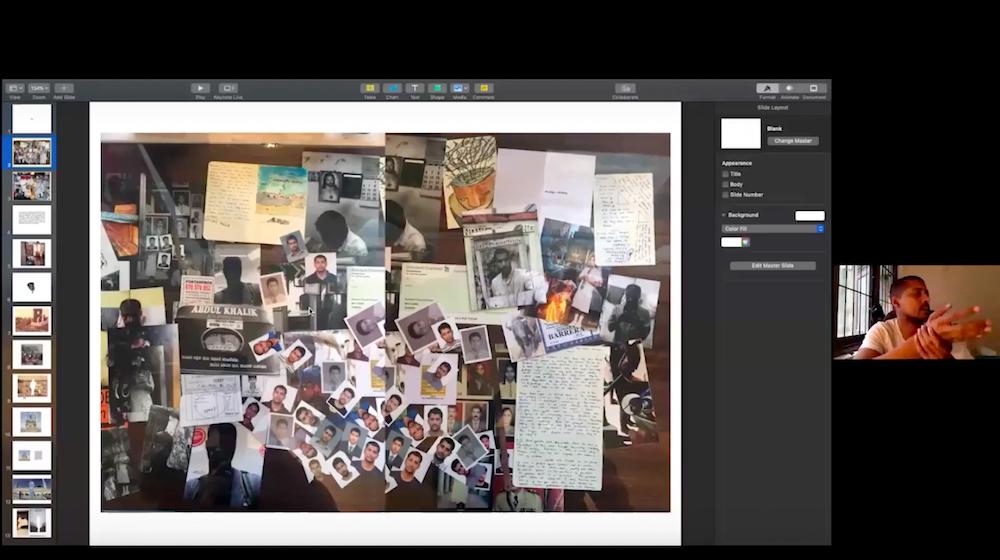

Azeez’s practice assumes a critical position in the way that it is immersed in a study of visual and popular culture in Sri Lanka. The artist steers towards a striking directionality that includes engagements with photography, family archives as well as socio-cultural critiques of technology, social media and other industries of consumption. Here, he shared a glimpse of the vast archive of family photographs that he has been working with.

Exploring an unravelling of the self in his practice, Abdul Halik Azeez returned to the aegis of his family photographs, sharing his multimedia work, My Self. Azeez dipped into the vulnerability of learning about one’s past, framing contemporary Muslim identity in his readings of the subjectivities of post-war Sri Lanka against the rising Islamophobia, hate speech, and global shifts affecting the island. A micro-investigative practice, Azeez grasps the family photograph as evidence, dealing with the image as a disembodiment of the past. Culled from an intangible context, it allows him to revisit the memories and histories of his family, over years of confronting the realities of migration, mental health, wealth and education in neo-liberal economies. He reflected on the role of technology and his experiments with machine learning and photography, mediating his exercise of decoding his past as well as the documents that he has produced as part of his ongoing work.

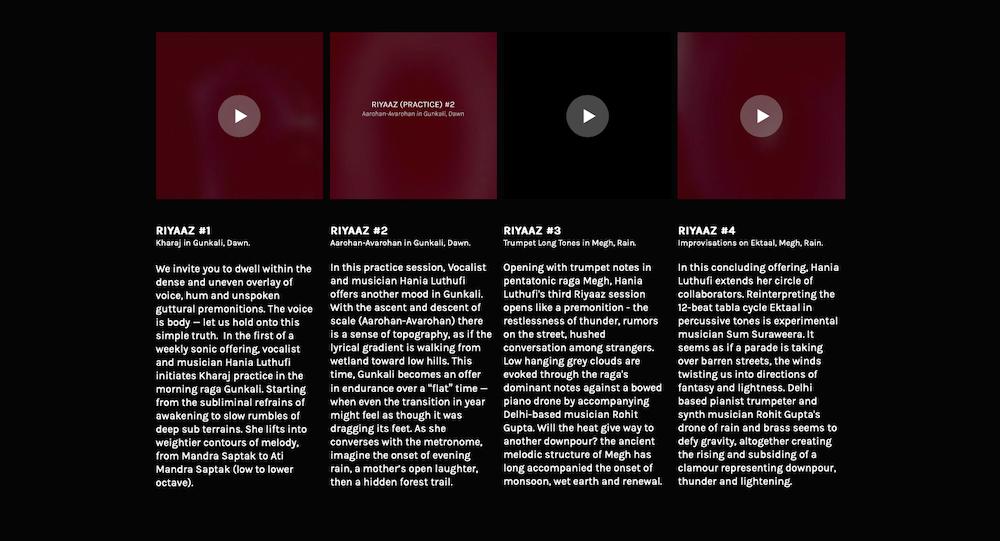

A screengrab of the Colomboscope webpage featuring Hania Luthufi’s Riyaaz series, each a dwelling on sound and soul.

Part of the digital programme "#HeldApartTogether" at Colomboscope, Hania Luthufi spoke about the sonic textures of occupying, and being occupied by, the silence of a space. Luthufi referenced her frequent—but now disrupted—travels to Tiruvannamalai in Tamil Nadu, and her time in the Kataragama temple complex in Sri Lanka. Aware of how spaces are defined by sound, Luthufi expressed her perceptions of these spaces, drawn by the din of devotion and the echoes of contemplation that unite such sites. She shared an audio recording that brought together her research on ragas for the goddess Saraswati, and her recurring considerations of the word, sukūn. Drawing on childhood associations where sukūn meant the circular diacritic placed above a consonant in Arabic, Luthufi found herself staying with the weight of tranquillity she had memorised with the word. Her recording, a meditation on the dramaturgy of a breath, demonstrated her haptic approach to listening as characterising the peace of the mundane.

A conscious grouping of praxis and possibility, the “Artist Encounters” series at Colomboscope offered a peek into the making of an immense tapestry of voices. It supplemented the curatorial vision for the festival by making otherwise unheard insights available to viewer-listeners. Almost pedagogic in their expanse and depth, the conversations staged critical exchanges of their own, propelled by the virtual in its ability to traverse contextual and physical distances.