Impulses in Institutional Archives: A Panel Discussion on Archival Futures

Can the structure of archives contain, represent and render anti-institutional impulses and counter-cultural histories? What does, or could, this archive look like? These questions formed the refrain for a panel discussion on “Archival Futures” as part of The Photographers’ Gallery and Paul Mellon Centre’s three-day conference titled Concerning Photography: Photographic Networks in Britain (c. 1971 to the Present). The session was moderated by curator Rahaab Allana, with presentations by archivist and researcher Charlene Heath, and art historian Fiona Anderson. Their discussion foregrounded pertinent tensions in the field of archiving today, deliberating the inherently “muffling” (Heath) effect that institutional archives have on histories that are, as Allana called them, “unbound and free-wheeling.” They spoke about whether the purpose of an archive is to preserve the intentions and narratives of those who produced it, or if these should (or perhaps, will) be circulated, unpredictably, taking on material lives of their own. This piece reflects on the provocations raised by the panellists and the audience, and the intriguing life that archival materials lead when presented in discursive spaces through specific narratives and lenses.

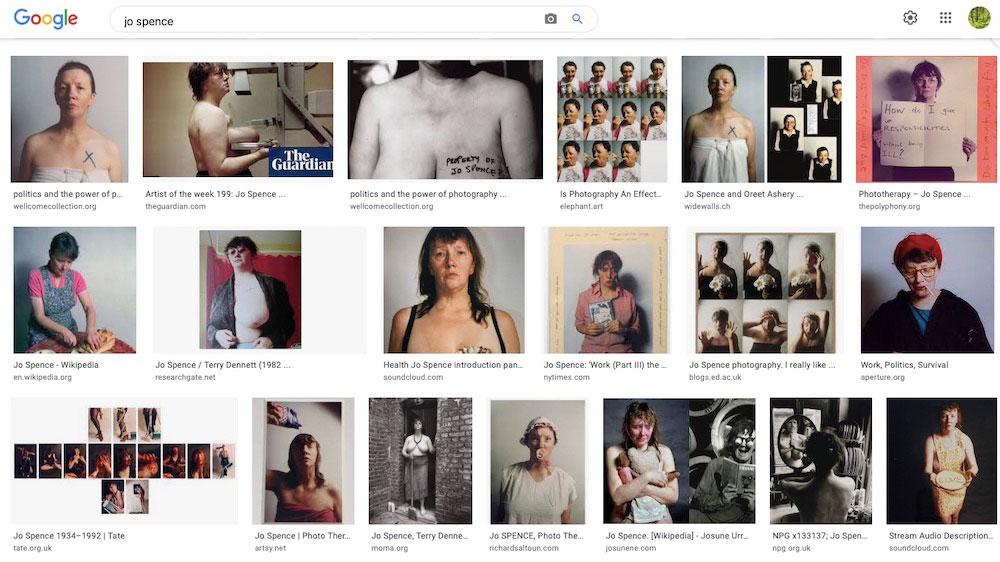

Heath presented on her work as Archives Assistant for the personal archive of Jo Spence (1934–92) who was a British photographer, writer, cultural worker and activist. Spence’s leanings and preoccupations were with more popular forms of photography, and early on in her career she had started her own agency which specialised in family portraits, and wedding photos. In the 1970s, she became more immersed in documentary modes as part of socialist and feminist movements. Spence also created self-portraits of her battle with breast cancer as a way to destabilise idealised notions of female form. Heath underscored her polemic as clearly anti-establishment, particularly in the Photography Workshop (1974), which she started with one of her primary collaborators Terry Dennett. It explored the potential of photocopies, cheap print-outs and digital surrogates, as a way to “…challenge the art world and museum’s fetishizing photographs through conventions such as limited edition prints as collector’s items.” Heath expressed a conundrum, as an archivist, of preserving not only material integrity but the integrity of the material—of Spence’s polemic—and whether professional archiving could preserve this essence as it brought her life’s work into the fold of the archive institution. Heath flagged how Spence was being situated within lineages that she does not fit into neatly, such as with Cindy Sherman in American art history, and that acts of preservation have a tendency to fix pantheons and “mute anti-institutional motivations.” Instead, Heath proposes that archives of the future must “un-fix” and orient towards the motivations and energies that led to its formation in the first place.

Screengrab of Jo Spence searched on Google.

Anderson’s presentation focused on photographer, artist and educator Sunil Gupta. Examining how his work is being read as “archival,” it highlighted his “ambivalence” to the institutional frameworks in which his photographs are being assigned. Gupta’s focus has been on issues revolving around race, migration and queerness. His practice has been deeply personal. Anderson marked a life-altering phase of his life when Gupta was diagnosed as HIV+ in the early 1990s. It was soon after, Anderson explains, that he “…thought it might be time to see how the virus affects my life.” Along with documenting his experience in hospital, he also began to document shifts in gay life in London in this period—he wanted to record this “weird social history” of the mushrooming of sex clubs versus his isolation when he was hospitalised in institutions. Viewed in context of the increasing interest in queer visibility, changing experiences and medical advancements around HIV, as well as the fact that many of the bars he documented have since shut down, his photographs have taken on an archival quality. And yet, Gupta is weary of being deemed as an “AIDS photographer” or that his experiences of pain and loss are subsumed as “documents.” Anderson also warns of the partial nature of archives, of the gaps and fissures, and hints that perhaps what becomes increasingly absent are the urgencies and orientations of those who produce the documents.

Sunil Gupta: From Here to Eternity. (Mark Sealy, ed., London: Cornerhouse Publications, 2020. Image courtesy of the artist.)

Such presentations by archivists and researchers, and their positioning towards materials, put forth clearly that institutional archives are not neutral repositories. They are imbued with the concerns and questions of those who are involved in the process—not as merely cogs in an archive machine, but participants in determining the future lives of documents. The discussion as well as the question and answer session with the audience emphasised an interesting contradiction that is implicit in the need to illuminate the artist’s own concerns with their archives, which can potentially fall into the trap of authorial control over narratives. Indeed, while the work of the artists was located within wider histories of their time, the key determining factor for both presentations was the intent of the individual—where does this leave the unrestrained photocopies? This panel raised the dilemma that faces all those who are dwelling on archival futures—who controls the narrative?

To read more about the conference Concerning Photography, please click here, here, here, here, here and here.