Objects of Discourse: Magazines, Books

The afternoon panel of the second day of the conference Concerning Photography was titled “Magazines, Books.” It addressed the impact of printed and digital media on photography cultures. By pulling the focus back to artistic practices, it offered a glimpse of how photographs and the cultures of photography have been traditionally framed as objects of discourse between cultural producers and a growing, critically-engaged audience. In other words, the object of the photograph was connected to the swarm of affects, politics and technologically-mediated changes in publishing cultures of the United Kingdom; to inform the audience about how changes in the latter invariably told on the practices and methods of producing the former. Even as some of the presenters sought to train their focus on photographers, the session provided a wonderfully rich glimpse into the world of those who make decisions about publishing photographers, including showcasing their work on popular media such as television. It also shed light on the institutional work of recognition done by gallery-based publications and the radical acts of recovery in order to restore the charge of former provocations and lives—like that of the pioneering black photographer, writer and cultural historian of Ghanian-British descent, Maud Sulter.

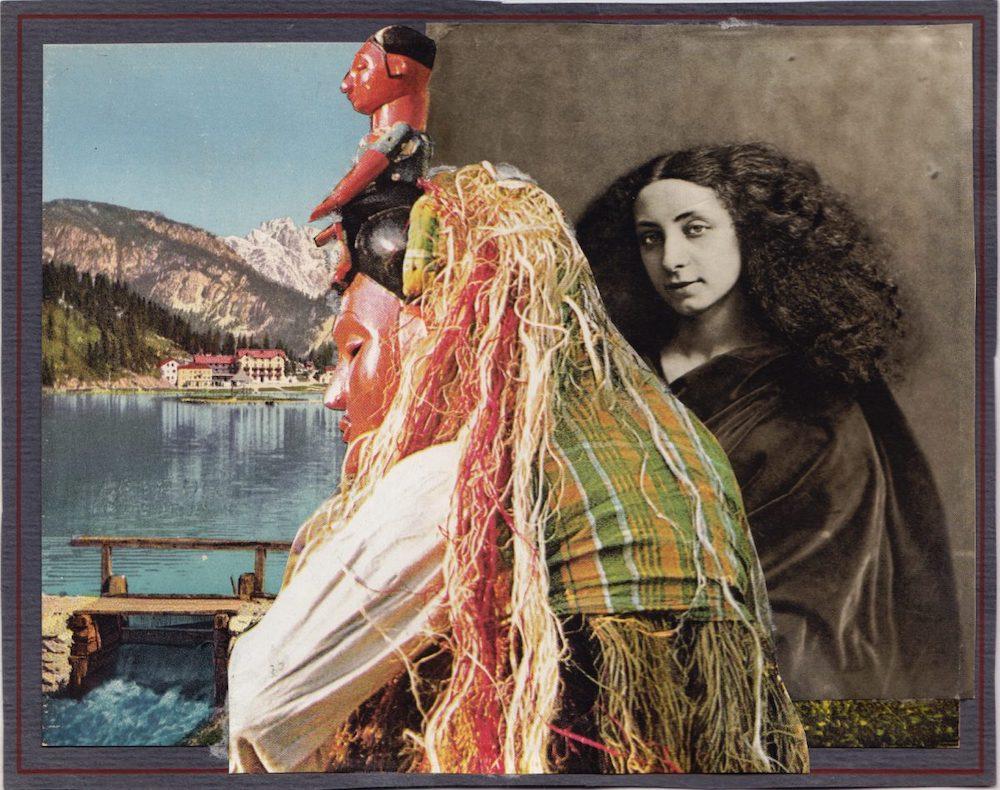

Maud Sulter's photobooks sought to centre black women in photography, especially those whose contributions to cultural life had been erased. The most notable ones included Zabat (1989), Hysteria (1991) and Syrcas (1993). (Image courtesy of Maud Sulter and Jacqueline Ennis-Cole.)

Sulter's last photobook, Syrcas (1993), was probably her most ambitious. The series combined postcard views of Europe, popular illustrations and symbols of African art, and portraits from the history of photography. Presented as a scrapbook, it tried to link the tragedy of slavery with the European holocaust in a continuum of human suffering. (Image courtesy of Maud Sulter and Jacqueline Ennis-Cole.)

The paper on Maud Sulter was delivered by photographer and curator Jacqueline Ennis-Cole. Through her intervention, she sought to highlight the gaps in public accounts of inclusive photographic practices in Britain. Sulter had a diverse range of practices—from making her own photographs to assuming the role of a cultural producer, usually publishing her own photobooks and poetry until an untimely death in 2008. Ennis-Cole made a powerful plea against cultural amnesia that can threaten to eclipse the work of influential pioneers, like Sulter, who often require the intervention of public institutions, galleries and archives to keep their exemplary practices alive for new generations of artists, writers and audiences. She emphasised the role of creativity in constructing dialogue between marginalised communities—especially between Black Feminist and LGBTQI communities—and held their social upliftment to be the most important factor in her curatorial as well as artistic projects. She positions Bernardine Evaristo’s Manifesto as a radical plan of action that shows us how cultural minorities can write their own stories from the margins and make their way to the centres of cultural power. Perhaps the most important metric of this change would be to see more women and people of colour in positions of power in the art-publishing world, Ennis-Cole suggested. It is through such interventions that the voices and visions of artists like Sulter can be preserved, engaged with, and prodded into new formations or guides for creative thinking about social justice.

The Photographers’ Gallery was founded by Sue Davies in London, 1971. They regularly publish photobooks and magazines, such as Loose Associations. (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)

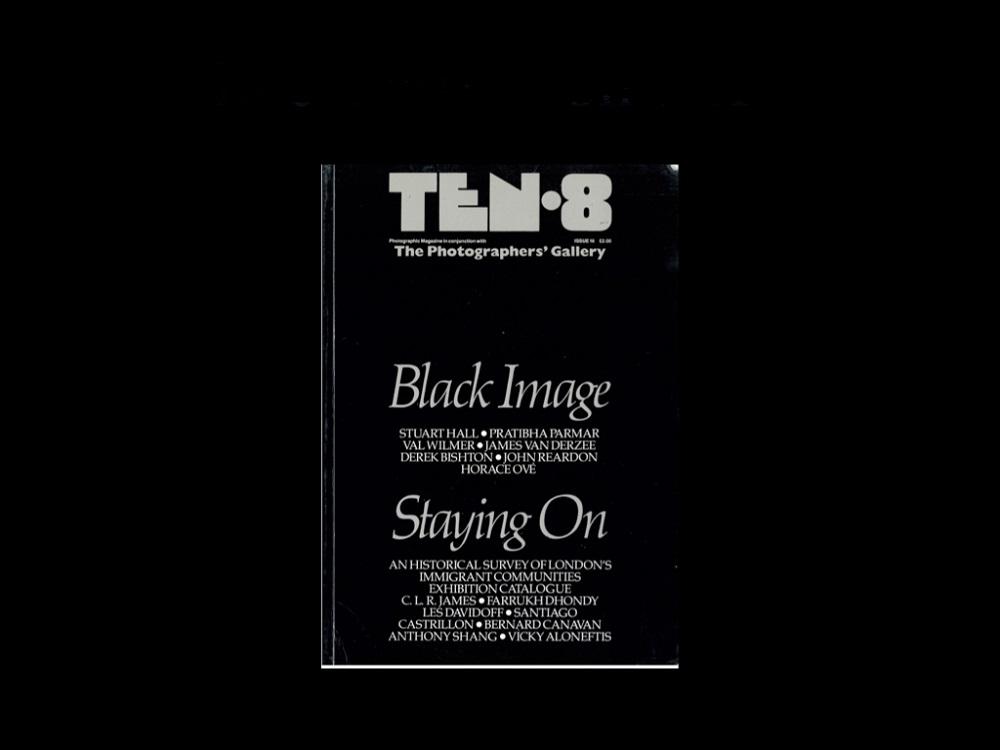

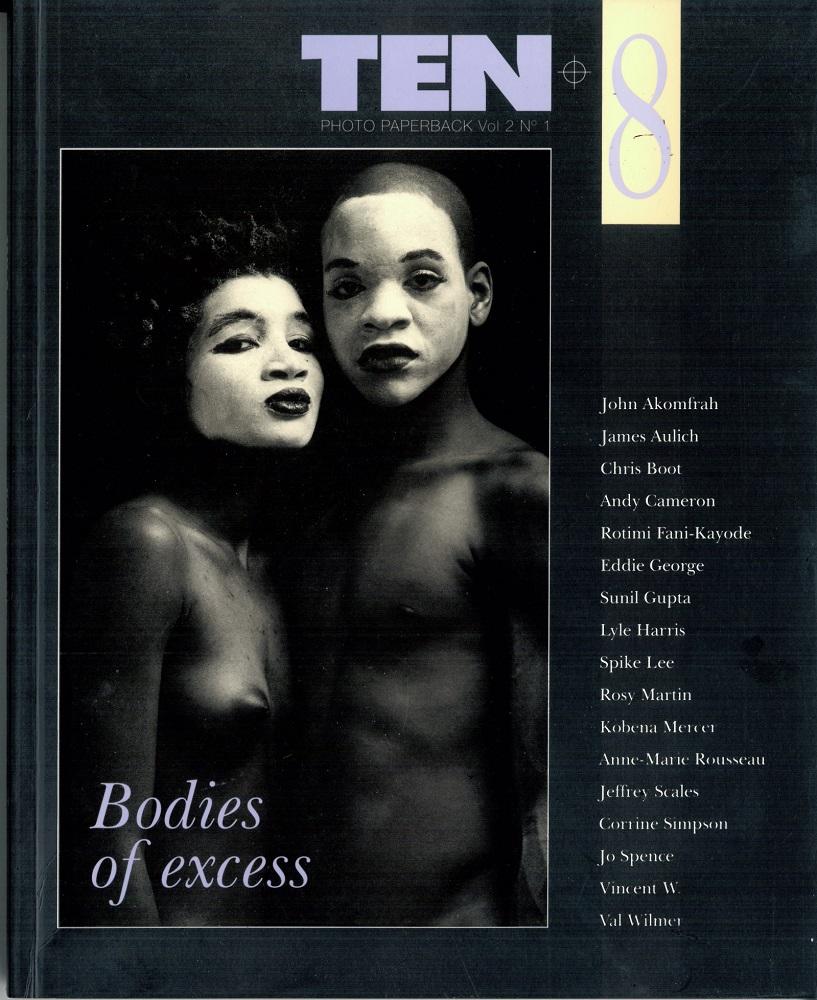

The other presenters also pointed out the lack of minority presence in influential institutions, whether at the The Photographers’ Gallery—which was the first gallery devoted solely to the arts of photography—or at the BBC—which represented the standard bearer of mainstream culture in Britain of the 1970s and 1980s. There are curious exceptions, however, that the presenters pointed out. Derek Bishton, in his paper on Ten.8—an influential independent photography magazine, which he was involved in editing and publishing in the 1980s and early 1990s—focused on how their predominantly white-male set up did not become a ground for complacent or passive receptions of mainstream photography culture. Many of their issues focused on the politically problematic and socially injurious policies that were gripping Britain in the 1980s. The impact of documentary photography was especially put under the radar of their regular analysis, featuring diverse sets of critics and writers from Birmingham—where the magazine was based—and beyond. From a regional, local concern, it grew to command nearly 5000 subscribers when it folded in the 1990s. By this time, it had become a photobook publication, instead of a quarterly magazine. Perhaps the most influential thinker on their project was the great British-Jamaican Marxist cultural theorist, Stuart Hall. Hall’s explorations of the exploitative relationship between realistic photography and minority, especially black, subject-formations through the prism of what is innocently described as “documentary photography” was a crucial insight for magazines like Ten.8 that tried to highlight social justice as a unique problem that photography and critical awareness around image-making could actually combat. Whether highlighting police atrocities on black and Asian populations, or the prevalence of anti-feminist and white-nationalist movements, or simply documenting changes in the tools that were available for critically analysing photographic images—which accelerated under the impact of digital technologies in the early 1990s; Bishton suggested that the rhizomatic impact of their magazine allowed it to be thoroughly absorbed into the bloodstream of British image-making cultures. Copies of the magazine may be held in archives, but their impact on contemporary culture has clearly spilled out of those confines.

Ten.8 Magazine was started in 1979, publishing quarterly issues out of Birmingham, England. Their independent editorial eye and critical focus on contemporary photographic cultures marked them out as a magazine of note. (Image courtesy of Derek Bishton.)

Ten.8 Magazine issues frequently advocated for greater social justice, especially regarding race relations. Their championing of black artists like John Akomfrah or cultural theorists like Stuart Hall was also significant in altering the landscape of British media representations. (Image courtesy of Derek Bishton.)

Hall’s figure is emblematic of several other changes. John Wyver’s presentation on how photography was represented on the BBC in those crucial last decades when it ruled as the primary public broadcasting service, in the 1970s and 1980s, also revealed a dense network of personalities and institutional privileges that determined this discourse. In spite of their largely male, straight, white identities, the voices that influenced programmes in different genres and formats—from talk shows like Parkinson to erudite, talking head-commentaries led by figures such as John Berger and Bryn Campbell or Alan Yentob’s Arena series—still managed to showcase a wide range of ideas about what photography was and what it could be for a critical public. From an early fascination with fashion photographers—deemed safely unpolitical—and the dizzy gloss of aristocratic aesthetics in the 1970s, cultural changes in the margins inevitably shaped a movement away from these to more critical engagements with the politics of receiving and producing images in a multicultural Britain. Aside from racial and class-political concerns, a concentrated effort was also made to feature the work of women photographers, whether in journalism or contemporary art, such as Dorothy Bohm and Jo Spence. Wyver’s belief that the BBC archives can provide a goldmine of primary visual texts on image-making cultures in Britain appears, therefore, to be a legitimate one. The hope that it will be opened up to more researchers in its centenary year of 2022, as Wyver suggested, is a cause for excitement for postcolonial image-practitioners everywhere.

The BBC Television documentary series Arena, beginning in 1975, featured some of the most influential shows on critical photography and photographers for the public broadcasting service. (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)

An exception to the overwhelming gender homogeneity in British publishing and galleries was the role played by Sue Davies in opening The Photographers’ Gallery in London, in 1971. Davies was perhaps equally influential in mediating the impact of photographic cultures in Britain. David Brittain’s paper carefully explored her influence in what was otherwise a fairly clubby atmosphere of male photographers and curators. Through their influential gallery shows, focusing on the work of photojournalists like Margaret Bourke-White, Robert Capa, David Seymour and Sebastião Salgado; influential fashion photographers like Anton Corbijn; or women photographers like Taryn Simon and Alexis Hunter, among many others; their work represented a diverse set of eyes that were trained on a changing British society in its post-imperial phase. Their spread was more eclectic than independent zines but their commitments to social justice and critical analysis, especially of digital cultures, remain exemplary.

.jpg)

The Photographers' Gallery was the only one of its kind entirely dedicated to the art of photography in Britain. Sue Davies' influence shaped its agenda with exhibitions that balanced social justice themes with technological changes in photography, in shows like Concerned Photographers 1 (1973), European Colour (1978) and Modern British Photography (1981). (Image courtesy of The Photographers' Gallery Archive.)

If one agrees with the common perception that photographs help mediate our access to reality—with some taking us closer to its skin, while others take us away from it—then it would appear that the roles of magazines, photobooks and galleries attend to the ways in which photographs are themselves objects of mediation, relying on important frameworks of reference—whether institutionally bestowed or independently forged. As images and the sheer quantity of their originals as well as copies continue to grow on the exponential curve, these acts of mediation will require our critical judgment too. With an improvement in the quality of editors, publishers and cultural producers, as well as more added members from minority groups, the source of the fountain can be either refreshed or contaminated in creative ways, or allowed to gush unchecked—flooding the world in a stream of indiscriminate pictures. Ennis-Cole’s cautious words were quietly enshrined as the last ones on this issue.

To learn more about the conference Concerning Photography, organised by The Photographers’ Gallery and the Paul Mellon Centre, please click here, here, here and here.