World-Changing: Disability, Debility and Cinema in We Make Film

Directed and produced by Shweta Ghosh, with Assistant Director Priyanka Pal and sound recording specialist and Ghosh’s co-cinematographer Sumit Singh, We Make Film (2021) throws a radical premise at its audience: what if frameworks of knowing and experiencing disability require approaches that exceed accommodationism? As Ghosh wonders further, in a voiceover, what if “...it means changing the way the world has been built so far.” We Make Film begins with the promise to understand what such world-changing would include, and it does so by embracing both the indeterminacy of its own position and relinquishing the sovereign role of the filmmaker. Ghosh identifies as a member of the community by “association” and is alert to the dangers of speaking on behalf of persons with disability. Ghosh and her sister have grown up assisting their father Samir Ghosh, who has a physical disability, in making images.

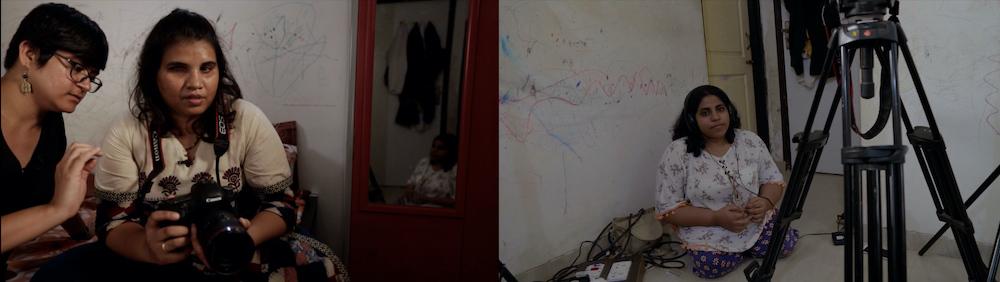

Director Shweta Ghosh with Assistant Director Priyanka Pal during the filming of We Make Film.

The film opens with Ghosh discussing a shot with her father and the differences in their approach emerges through their gentle banter. Later, Ghosh and her father discuss how terms such as “collaboration” can often conceal the infringement on a person with a disability's perspective, that is amended in the process. Ghosh argues that when she is assisting her father in taking a shot, her personhood is also present in the inputs she gives. Her father highlights that such an exchange, however collaborative, is distinct from individual intentionality, and he is drawn to the possibilities of the latter. This is a critical exchange, for it expands the frame of the documentary from the binary of disability and capacity, to include debility as defined by Jasbir K Puar in The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability (2017):

“The term ‘debilitation’ is distinct from the term ‘disablement’ because it foregrounds the slow wearing down of populations instead of the event of becoming disabled. While the latter concept creates and hinges on a narrative of before and after for individuals who will eventually be identified as disabled, the former comprehends those bodies that are sustained in a perpetual state of debilitation precisely through foreclosing the social, cultural, and political translation to disability.”

We Make Film relies on graphic tools to depict the discriminations inherent within an ableist society and what disability justice may entail through the use of white and multi-colour dots as motifs for homogeneity and diversity.

Samir Ghosh observes that able-bodied people “praise you and pass you by.” Inaccessibility is aggravated by a mediatic culture that is resistant to new ways of apprehending cinema, requiring persons with disabilities to make concessions and adjustments. This echoes what artist Carolyn Lazard states elsewhere in a video work on subtitling as an able-bodied intervention that seeks to assert an artificial yet seamless flow between visual reality and textual representation. Lazard emphasises that we need “Work made from the conditions of debility and difference, not translated for debility and difference.”

Left: Anuja Sankhe and Ghosh discuss camera and direction techniques, framed by the camera place infront of Priyanka Pal.

Right: Pal following the conversation between Sankhe and Ghosh on direction and camera movements, framed by Sankhe's camera.

Ripples of this emerge in Ghosh’s exchange with award-winning journalist and bank employee, Anuja Sankhe, who has a passion for writing and making films with disability narratives. Ghosh asks Sankhe, who is visually impaired, if having braille markers on camera buttons would help her in controlling the device. Sankhe agrees, but stresses that she would still not access the frame with the immediacy and velocity that image-making has assumed. This exchange rips open the failed promise of the neoliberal discourse on “accessibility accommodation,” and asks instead: what if, alongside infrastructural improvisations and collaborative synergies, we could dream of forms of cinema that do not rely on audio and visual mediums as its primary components? We Make Film grapples with this as it begins with and returns to Julio García Espinosa’s 1969 essay “For an Imperfect Cinema.” The quote runs as follows: “We know that we are filmmakers because we have been part of a minority which has had the time and the circumstances needed to develop, within itself, an artistic culture; and because the material resources of film technology are limited and therefore available to some, not to all.” To think of what possibilities cinema could hold when wrenched free from the material limits that exclude, erase and exploit disability and debility, is the question at the heart of this film.

Filmmaker Mijo Jose enquires about the alignment of the camera tilt to the We Make Film crew.

Another aspect of Espinosa’s concept of Imperfect cinema informs the methodology of We Make Film: “Imperfect cinema is an answer, but it is also a question which will discover its own answers in the course of its development.” Ghosh states this clearly: she is not seeking a resolution to her own questions about disability inclusion in creative industries. She is learning and listening, understanding perspectives and imaginations beyond her own. In a segment that focuses on filmmaker Mijo Jose, who runs a photo studio, produces short films and has a hearing impairment; Ghosh hands over the process entirely to Jose, who has just received new equipment and is keen to explore it. Jose films a shot, with Ghosh on the other side of the camera, and asks her about how she believes disability can change production processes. An outstanding part of the documentary, Ghosh notes that she is no longer making a film on Jose, but with Jose. Letting three collaborators and the crew—who feature prominently in the documentary—take the lead in shaping conversations reveals invaluable insights. Sankhe complains that audio descriptions track narrative developments (such as, X walked from point A to B) but do not relay cinematic choices (Did the camera move with X? Did X vanish into the horizon while the camera stayed still?). Debopriya Ghosh, an animator, artist and the third collaborator to be featured in the documentary, informs the crew that merely plugging in a hearing aid is not enough; she must acknowledge a sound. Debopriya’s mother brings up the exclusionary experiences at educational institutions; Jose lights up when he describes his transition to a school dedicated to children with hearing impairment, a place where he could interact and engage freely with others through sign language.

Debopriya Ghosh explains the process of acknowledging and developing comfort with sounds. Debopriya is an illustrator and animator whose work focuses on experiences of hearing impairment.

We Make Film treads the multiple paths of discovering who its collaborators are, what they think and what their creative projects may become, through exchanges that foreground comfort and sharing. In questioning the constitution of the cinematic medium as an exclusionary site, the limits of the optic-aural media, and the labour of challenging its frontiers; the documentary centres the material and epistemological discontents identified by debility and disability movements.

We Make Film is screening online till the 14th of November as part of the Dharamshala International Film Festival 2021.

All images from the film We Make Film by Shweta Ghosh. 2021. Images courtesy of the director.

To read about some of the other films playing at the festival, please click here, here, here and here