The Living Statue: Photographing Masculinity in a Body-Building Manual

In the visual history of defining the masculinist athletic form, few can claim to parallel the influence of body-builder Eugen Sandow (1867–1925). Among the twentieth and twenty-first-century icons, perhaps only Tarzan, Muhammad Ali, Arnold Schwarzenegger and David Beckham are comparable figures. Besides lending his name to the ubiquitous Sando genji or vest, the Prussian strong-man was successful in institutionalising regimes of the body (predominantly, but not exclusively, cis-male) which could then be exported across the world as a commodity. Through a wide array of merchandise and publications carrying his image, Sandow tapped into—or perhaps revived—a spectacular culture of the idealised male form drawing primarily on Greco-Roman classical sculpture, photographing himself as archetypal figures such as the Farnese Hercules, the Discobolus, and the Dying Gladiator or Gaul. According to his biographer, Carey Watt, during Sandow’s visit to India between October 1904 and June 1905, he captured the popular imagination with multiple performances at the Theatre Royal and the Corinthian in erstwhile Calcutta, with “…two special appearances ‘for natives.’”

In Bengal, the early decades of the twentieth-century witnessed a rise in different strands of physical cultures. There were some, like Jatindra Charan “Gobar” Goho, who were professionalising older traditions of wrestling and entering the competitive sphere; while others, like Pulin Behari Das, were drawing on indigenous practices of lathi-khela (stick-fighting) and fencing to train revolutionary nationalist groups. Historians of physical cultures—like John Rosselli, Indira Chowdhury, Mrinalini Sinha and Abhijit Gupta—have seen this as a nationalist response to derogatory colonial stereotypes (often culturally internalised) of the Bengali male as “effeminate.” However, there were other groups who were responding to the international circulation of these images and ideas.

Muscle Control and Barbell Exercise by BC Ghosh and KC Sengupta. (Kolkata, 1930. Front Cover. From the collection of Sujaan Mukherjee.)

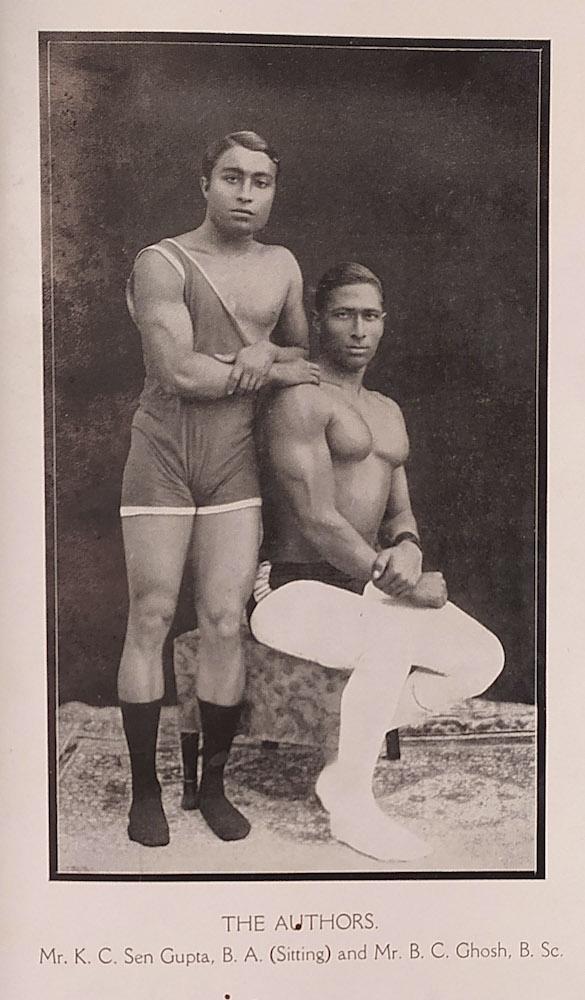

Mr KC Sen Gupta, B.A. (Sitting) and Mr BC Ghosh, B. Sc. (Standing), the co-authors of Muscle Control and Barbell Exercise.

One such was the akhara of Bishnu Charan Ghosh, co-author of a manual that resembled in its visual language the publications brought out by Sandow, Charles Atlas and Maxick (propagator of the Maxalding system). Like their counterparts from the global north, we find Keshub C. Sen Gupta and Bishnu Charan Ghosh’s Muscle Control and Barbell Exercise (Lakshmibilas Press, 1930) offering not only instructions for trainees but also advice on lifestyle and social morality.

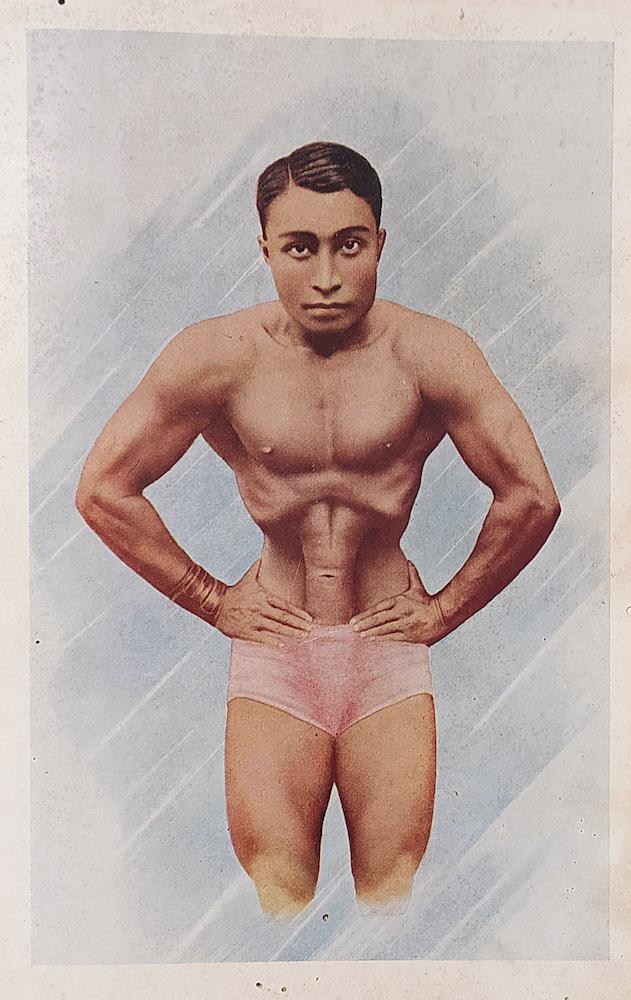

KC Sen Gupta in Muscle Control and Barbell Exercise. (Kolkata, 1930.)

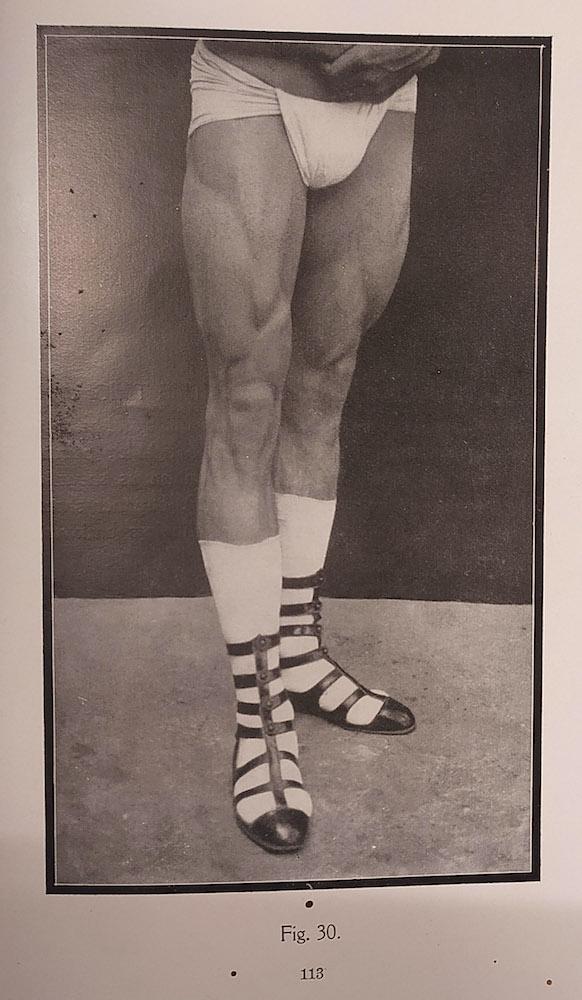

Mr Preston of the Calcutta Police in Muscle Control and Barbell Exercise. (Kolkata, 1930.)

Apart from a single colour plate that is attached to the front endpaper, the book contains forty-two photographs illustrating techniques and postures, accompanied by brief notes. Most of them appear to be cut-outs of photographs placed on black backgrounds—possibly to accentuate the muscular contours—identical replicas of Maxick’s Muscle Control (Ewart, Seymour & Co.). In many of them, particularly in Sen Gupta’s section on barbells, we find the models wearing sports briefs; while in the latter half, Ghosh’s students are more adventurous. Some wear shorts with gladiator sandals—much like Sandow—while others opt for a more primal look with tiger-skin briefs. Only in one photograph—that of RN Guha Thakurta, who is identified as “Our Guru”—we find a white cloth brief with a red belt tied around the waist, in the manner of the indigenous martial dancers of Bengal.

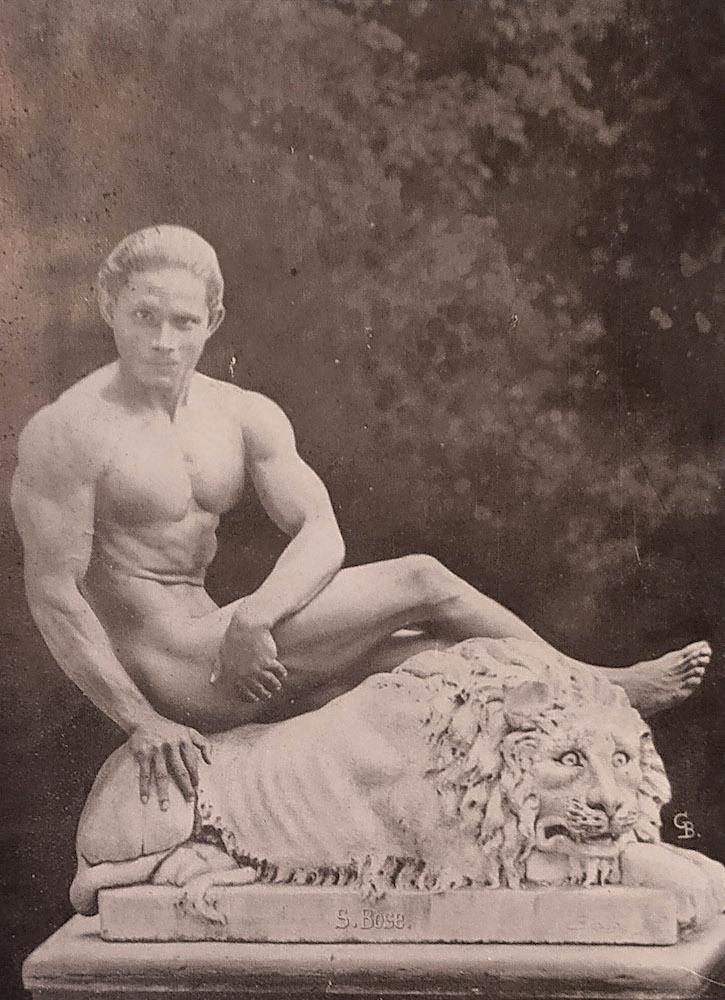

“The Panther on a Lion.” Posed by S. Bose in Muscle Control and Barbell Exercise. (Kolkata, 1930.)

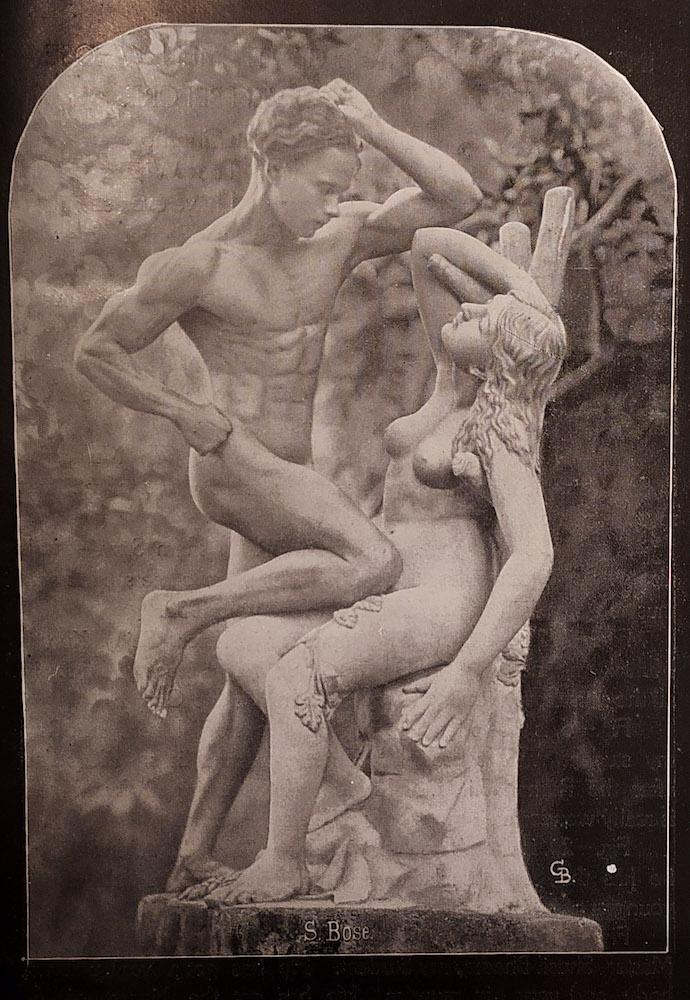

“The Living Statue.” Posed by S. Bose, with a marble statue in Muscle Control and Barbell Exercise. (Kolkata, 1930.)

Towards the end, Ghosh goes into raptures about one Mr S. Bose, who he confesses “…has the best muscular and the most uniform body, among all my students and friends… I love him like my own brother.” With his hair brushed back, Bose strikes more adventurous poses than any of his peers. The first in the series features him standing up straight and looking into the distance, while the second is captioned “The Panther on a Lion.” It shows him in the nude with a singularly smug smile on his face, sitting atop a marble lion that looks distinctly uncomfortable. The third one, captioned “The Living Statue,” is even more unexpected. Once again in the nude, Bose stands against a nude sculpture of a woman—the likes of which one encounters in the gardens of Bengal’s zamindari mansions—with his right knee resting on her lap. While there is an overt attempt to represent the male body in a heterosexually charged position vis-à-vis the female statue—offering interesting contrasts between two types of objectifications—the homoerotic potency of these photographs cannot be overlooked. It is unlikely, however, that documentary evidence of their circulation as objects of male desire will be forthcoming, as was the case with Sandow’s continuing popularity among gay circles.

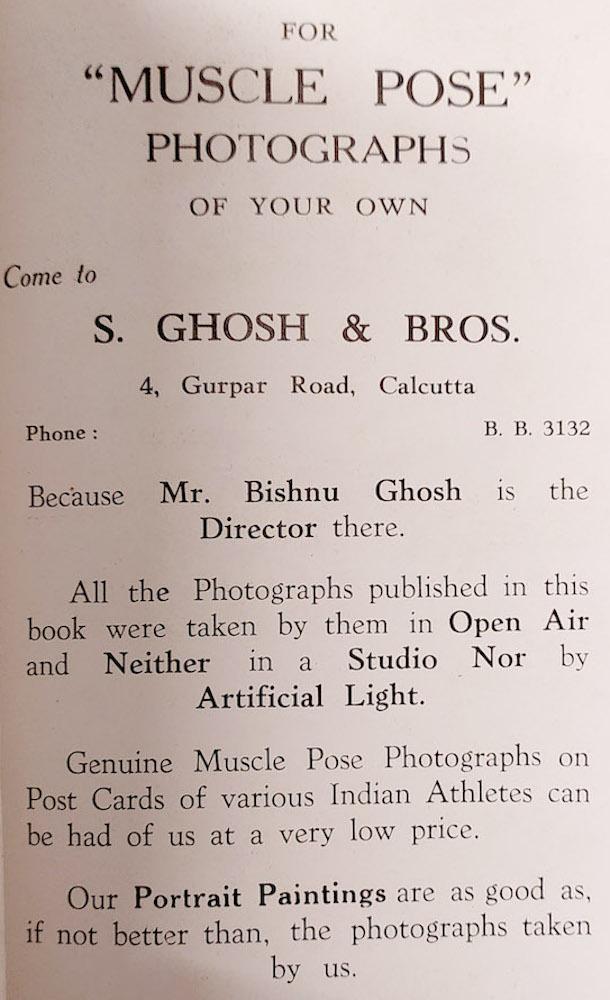

Advertisement appearing in Muscle Control and Barbell Exercise. (Kolkata, 1930.)

In the closing pages of the book, there are advertisements for S. Ghosh Bros.’ photographic studio, allied to Bishnu Charan Ghosh’s akhara on Gurpar Road (North Kolkata). We learn that they also sell “…muscle pose photographs on postcards of various Indian athletes,” and that “All the photographs published in this book were taken by them in open air.” Tantalisingly, we are also told that they offer portrait painting services which “…are as good as, if not better than, the photographs taken by us.” Perhaps an archive of these paintings will emerge one day.

To read more about masculinity and body-building, please click here.