A Space of One’s Own: An Interview with Tenzing Dakpa

Night. (Gangtok, 2015. Archival Pigment Print.)

In the second part of an ongoing conversation with Ketaki Varma, photographer Tenzing Dakpa unpacks the aesthetic choices that informed the making of his photoseries The Hotel, published as a photobook by Steidl in 2020. He reveals his fly-on-the-wall approach towards making this series, the process of capturing his family and their reactions to the final work and how the work took on a life of its own in its iteration as a photobook.

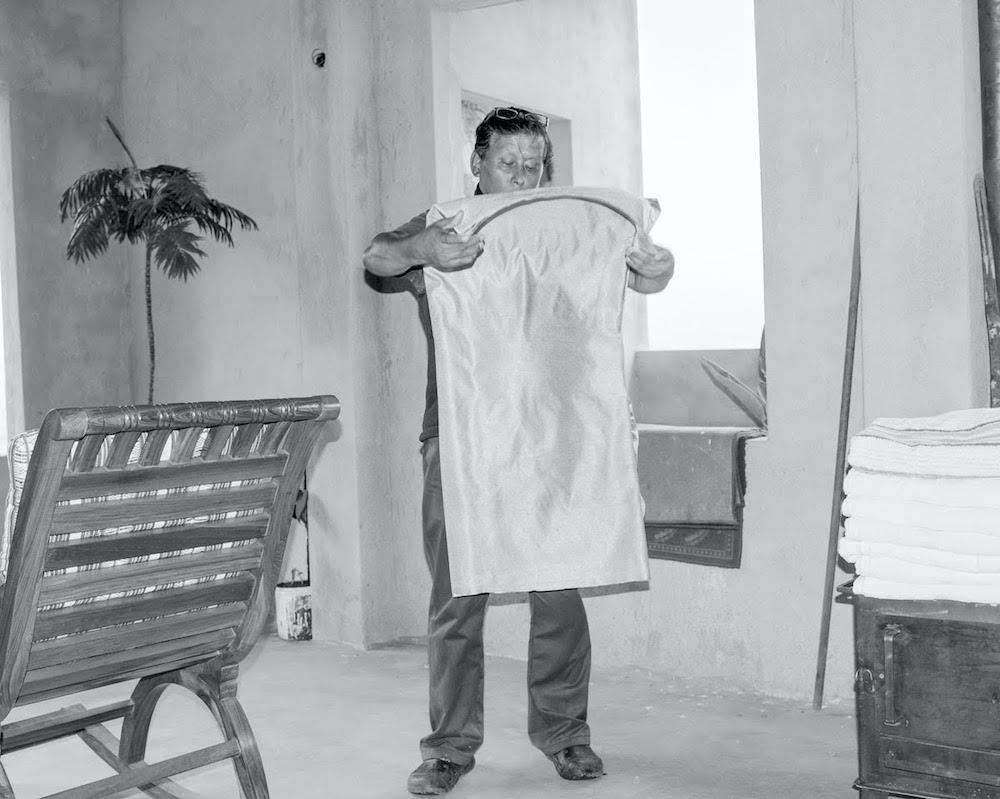

Folding Curtains. (Gangtok, 2015. Archival Pigment Print.)

Ketaki Varma (KV): Several photographs in The Hotel feature your family. As the only member of the family not involved in the hotel business, I wonder if the process of making these photographs revealed something unforeseen in your relationship with your family…

Tenzing Dakpa (TD): When I initially started making the photographs, my father was apprehensive and asked what I was doing. I did not have a straight answer but I responded by saying “I do not know who you really are.” I told him that through these photographs, I wanted to explore the idea of home, labour and migration—which were some of the realities I was preoccupied with. In retrospect, it was a way for me to enter into a photographic realm. My family got used into the fact that I was there to make photographs and just let me be. It was the first time that I was following them around with a camera, and I think I actually became non-existent. They were supportive of what I was doing, and there were instances where they would perform for the camera.

When I was in the process of making these photographs, I felt like my education in photography had found a home. Each of us was doing what we knew best. When they flew to Providence for my thesis show, my parents could not stop laughing at each other, commenting on how they looked in the photographs. It was mostly because they are so aware of their roles, how they operate and the demands of the labour that goes into the hotel. I think the photographs reflect my upbringing too—where there is very little communication yet stuff happens, things are repaired, maintained and cared for.

Scissors. (Gangtok, 2015. Archival Pigment Print.)

KV: The Hotel has a cinematic quality to it. Each image looks like a film still: the way the flash is used, the black-and-white tone, the way the subjects occupy the frame, etc. I am curious about your aesthetic choices. Could you tell us more?

TD: The way to access the hotel and my family photographically came from a pre-existing set of images of my cat, Dungkhar, which I had made over one summer (2014) before moving to the Rhode Island School of Design. I could not necessarily make the cat sit in one place or the other, so the process was just me following him around or the scene presenting itself within the premises of my home. So, a camera in hand always was an efficient way to go about it.

Playing off of this, the pictures in The Hotel have a fly-on-the-wall aesthetic in the sense that I did not want to stage any of them. The process of making these images was rife with anticipation and guided by intuition. The pictures in the series were all made on a Nikon D800e with a pop-up flash and a wide-angle lens. Since my parents were moving around most of the time, the wide-angle framing and the flash allowed me to respond and move faster as well. I consciously chose to shoot in black-and-white because I wanted to focus more on the gestures.

Prowl. (Gangtok, 2014. Archival Pigment Print.)

KV: Photobooks have a personal element to them—they offer a sort of intimacy between the photographs and the viewer that is different from other forms of display. One can experience them individually and can interact with them in a very tangible, physical sense. What made you consider turning this series into a photobook? Could you talk to us about the design?

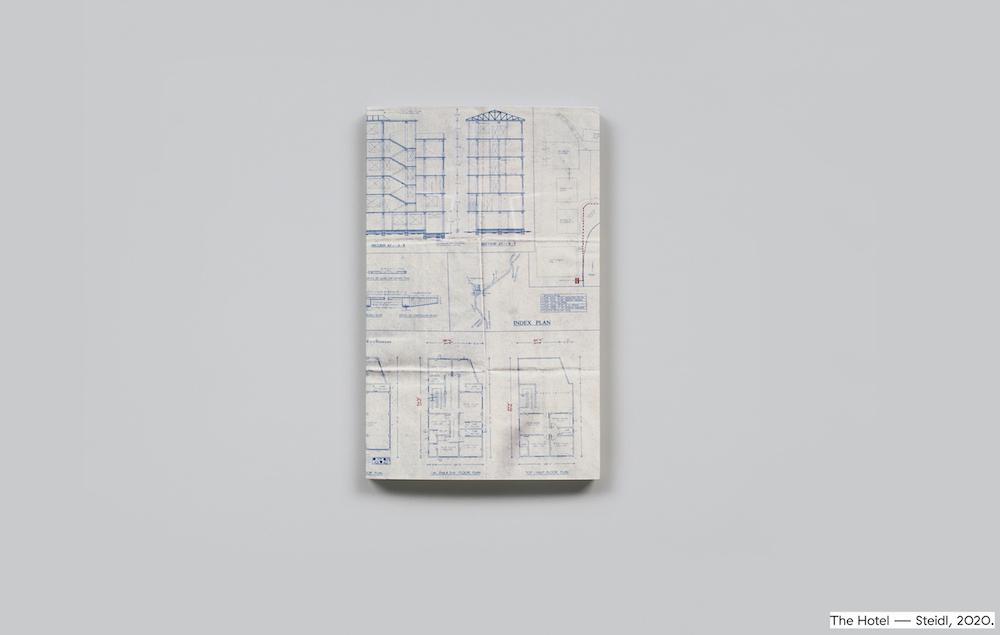

TD: The motivation to push the work into the book format came from this desire to give the photographic work a voice of its own—a voice that materialises in a physical form and functions along the lines of literature, imagination and narration. The structure, physicality and the lifespan of the photobook is a premise that works towards that conversation. The photobook, once it leaves our hold, becomes a vessel and a touchstone for personal belief and application. It is imbued with a sense of duration, rhythm and progression—demanding physical contact for its unearthing.

Book Cover of The Hotel. (Text and Book Design by Tenzing Dakpa. Forty-Five Black and White Photographs Tritone. Otabind Softcover with Dust Jacket. 19 × 30.5 centimetres. Germany: Steidl, 2020.)

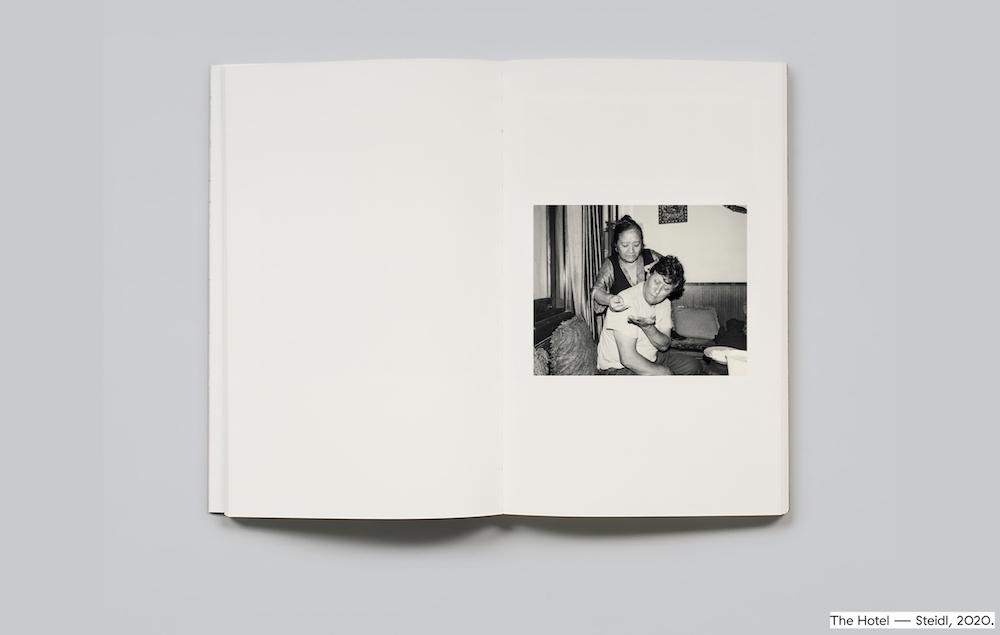

Lovers 02. (Gangtok, 2015.)

Aspiring to make a body of work that centres around my parents’ labour as a photobook is to set up a parallel universe in which my parents are engaged with a place they built and one to which I can always return. Coupled with this aspiration, this photobook carries for me the nuances that both complicate and endow this place with value. Further, the circulation of the photobook permeates both time and geography, thereby existing within a larger social, historical and photographic context. The spectrum of emotions and nuances that set the context for The Hotel best unfold, for me, within the photobook.

All images from The Hotel by Tenzing Dakpa. Germany: Steidl, 2020.